Thinking about the costs and benefits of migration for existing residents

New data from my FOI request underlines the diversity of migrant outcomes & the argument for a more selective approach

A country with more people in it will normally have a higher GDP. But what matters to most people is their standard of living. Russia has a bigger GDP than Australia, but Australia has a much higher standard of living. And you are less likely to fall out of a window down under.

The standard of living in different countries can be measured in different ways. GDP per capita comes closer to describing living standards.

Looking at median earnings even is better, as it reflects the distribution of income, as well as the total amount.

We’re also interested in productivity: how many hours people have to work for their income.

But there’s a lot which even these measures don’t include: the cost of living and housing are hard to compare between countries.

And other less tangible factors, which make a big difference to the quality of life, are even harder to measure. For example: French people have a lot more space than the English: England has 86% of the population of France, in an area one-fifth the size.

A lot of the media commentary on migration still seems to assume it leads to some sort of economic bonanza, a position that is increasingly untenable.

In previous posts I have argued for a more selective approach - to make Britain the grammar school of the western world.

As an upfront caveat to this piece, my argument that policy should prioritise people who will bring greater benefit to the country is not to pass judgement on the worth of people who would not make such a big economic contribution. The sort of economic discussion in this post can seem very cold. People are people, and may be wonderful grannies, good listeners, excellent friends and so on...

But the test for the government’s migration policy should be whether it improves the quality of life for existing residents.

Here is how I think about the costs and benefits:

1) Dilution of the capital stock

One first thing to consider is that migration means the UK’s capital stock is divided between more people.

Migrants may bring skills and their ability to work; but they cannot bring a mile of motorway; a large piece of industrial machinery; a house, a GP surgery, or an acre of land.

The nature of capital stocks is that they have often built up over quite long periods, so the marginal flow of new capital doesn’t change the overall stock much.

In an ideal world our stock of stuff would grow much faster than the number of people. As a result, there would be more stuff to go round, making us more productive.

In super-productive, capital-intense Britain you would get a seat on the train and hammer away on your laptop; you’d not waste time in a traffic jam; you’d use the latest bit of kit at work; or perhaps work in the shed at the bottom of your gigantic garden. Drudge work would be automated, and people freed up to get paid more doing those things only people can do.

While new ideas and ways of doing things are most important thing of all for growth, there’s an incredibly tight correlation between capital stock per worker, and output per worker.

Having large amounts of migration means splitting or diluting that capital stock between more people.

The table below compares the growth of different types of capital over the last decade to the rate of migration - the share of the population who arrived since 2011.

It isn’t intended to be some sort of definitive econometric analysis of the effect of migration on capital intensity: I just want to give you some intuitive idea of the effect I am banging on about.

Obviously you can take some of these questions further and start to look sub-nationally - the effect on things like housing is very locally concentrated: for example, the effect on London’s housing market.

For England as a whole the growth of the housing stock was only just greater than the growth of the population accounted for by migration, putting upward pressure on housing costs. In London the growth of the population accounted for by migration was actually greater than the growth of the housing stock - making that upward pressure even sharper.

On a sore point

For the UK this issue about capital dilution is particularly significant, because a lot of economists would agree on two points about the UK economy.

First, the UK has a problem about fixed capital investment. For many decades we’ve tended to be at the bottom of international league tables for investment in physical stuff that can drive productivity: buildings, machines; equipment and so on.

Things like the new ‘super-deduction’ will help, but the problem is a long-running one, and won’t be reversed quickly. British firms installed about half as many industrial robots as France in recent years and about a tenth as many as Germany. South Korea has nine times more robots per manufacturing worker than the UK.

Second, the UK has a long-running problem about housing. We have one of the lowest rates of homeownership in Europe. The share of private renters who have to spend more than forty percent of their disposable income on housing is 38% here, compared to 25% in the Eurozone.

There’s been a lot of discussion about the fact that 48% of heads of households in social housing in London were born overseas. But much less about the fact that 67% of private rented households in the capital are headed by someone born overseas. It’s just stupid to say migration is irrelevant to London’s housing challenges.

Migrants are not “to blame” for the origin of these problems. But for the UK, the effect of migration in diluting the capital stock further and adding to our housing problem creates a challenge in exactly the areas of our economy where we have long-term problems.

Recent very high levels of immigration have actually coincided with lower productivity growth, and this may be one reason why.

2) The fiscal effect: putting in and taking out

The downsides in terms of housing pressure and capital dilution might be offset if those who come are big net fiscal contributors, paying lots more in tax than they get back in services. If Bill Gates walked into your pub and started buying everyone drinks, you wouldn’t complain that the pub suddenly got crowded.

There is massive variation between different immigrants. As readers of my previous posts will know, my argument is that we should reduce migration and make it more selective, so that we reduce the downsides and maximise the net fiscal benefit.

Given the effect on capital dilution and strain on housing we want policy to select for migrants to be doing better than just paying their own way in terms of tax paid and spending received.

Different ways to look at the net fiscal contribution

Sensible countries like Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany and so on all do a much better job than the UK of measuring the net tax contribution of different groups of migrants. In the UK the data is frustratingly patchy and limited.

We can see that there is massive variation between different groups and that significant numbers of people who have come to the UK have had a negative fiscal impact, not a positive one.

Some people on twitter seem to have the idea that everyone who comes is paying in masses more in tax than they take out in spending. But this is not the case.

The following section looks at what we do know. Annoyingly, many of the statistical sources don’t record data on migration directly.

If we’re using census statistics we can see which people were born in another country, which makes life simple.

Unfortunately, other sources of data just look at people’s current nationality. Some migrants to the UK may retain their original nationality. But many migrants then get UK citizenship, so then count as UK nationals. That means current nationality is not a great way of looking at the longer-term effect of migration.

Other important sets of statistics that we might want to use to analyse the effect of migration only record ethnicity. This has the opposite problem to current nationality, as it blends together ethnic minority British people who were born here, or have migrated and become UK nationals, together with non-UK nationals of the same ethnicity.

Statistics by ethnicity are relevant to the debate about the long-term economic impact of migration, as long as we’re super clear that many of the people in different ethnic groups are British. The 2021 census for England and Wales gives a sense of how many.

Of those self-identifying as of Indian ethnicity, 44% were born in the UK. For those describing as Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnicity it was 55% and 59% respectively. 64% of those describing as Black Caribbean were born in the UK, and 36% of those describing as Black African. So in using ethnicity data we are looking at first generation migrants together with their children and grandchildren.

If people from the ONS or Home Office are reading this, it would be way way better if we recorded more data on migration, rather than just ethnicity or current nationality.

Net fiscal contribution

In their regular publication “Effects of Tax and Benefits on UK household income” the ONS calculates the balance of taxes paid and spending received by different households. It isn’t absolutely complete, and only includes a small part of the implicit subsidies from social housing.

But as far as I can see, this is the only official place we can see data on the question of net fiscal contribution.

Frustratingly and very unhelpfully, ONS have only ever produced analysis by ethnicity, rather than by whether people are migrants.

So the graph below is pretty much the only official source bearing on this question. It shows us that in the year ending 2019 white people were large net taxpayers. Ethnic minority groups as a whole were net recipients, but there was significant variation: Asian households were close to balance / small net taxpayers, while black households were substantial net recipients.

This aligns with the finding from all the studies listed by the Oxford Migration Observatory than non-EU net migration has had a net fiscal cost overall.

Many people will think this is not very helpful from a policy point of view, and they’re right. If we are going to make sensible policy or even have a sensible discussion the Government and ONS need to start producing something that looks at migration not just ethnicity.

We can see from earnings statistics that within each ethnic group those born in the UK unsurprisingly earn more than those born outside the UK. So if we looked just at British-born people from ethnic minorities, a greater proportion are likely to be net contributors than first-generation migrants are.

The ONS work on the effect of tax and benefits is the only ‘official’ estimate of the fiscal impact I’m aware of. It does underline the point recently made by David Miles from the OBR that we shouldn’t assume migration will be a net fiscal positive.

But it’s frustrating that this is the only official data: it lumps different countries of origin; different reasons for coming; and only gives us ethnicity not whether people are migrants.

So the rest of this section looks in a more detailed way at the variations in economic outcomes between different groups.

Households in low income

Whether a group of households are net contributors or net recipients depends on their employment rate, their earnings and also their family structure. Households with more children will receive more public spending. Lone parent households will also receive more in benefits.

The ONS publication “Households Below Average Income” provides analysis by ethnicity for equivalised household income - effectively combining the effects of employment, earnings and household structure.

This brings out the differences in economic outcomes between households of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity. This measure of low income is taken after people’s receipt of benefits, which compresses the differences.

This isn’t a measure of net tax contribution - however, low income and lower fiscal contributions are likely to be correlated.

The proportion of households of Indian ethnicity in low income has declined, and is now similar to the proportion for white British households. In contrast, households of black, Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity remain much more likely to be in low income.

We can also look in detail at the three main factors driving these differences in the proportions in low income.

a) Household structure

White British households are more likely to contain only pensioners. Households of Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Black African ethnicity are more likely to contain children. A larger proportion of black households are lone parents - one of the main reasons why Black people in England and Wales are almost three times as likely as their white counterparts to live in social housing.

You can see the effect of household structure in that black people earn more on average than people of Bangladeshi or Pakistani ethnicity, but are more likely to be in social housing, particularly compared to Pakistani households.

In contrast Asian households are more likely to contain larger families: both larger numbers of children and also more multigenerational living (a feature of Asian households I very much admire, and which happens even in high-income Asian households).

B) Employment

The census gives employment rates by country of birth. The variation is massive. For countries like Bangladesh and Somalia, the overall rate of employment is low and the rate of full time employment is very low (20 and 23%). Overall, working age people who were born in the UK had a higher rate of employment than people who were born elsewhere.

C) Earnings

The Labour Force Survey collects data on earnings by ethnicity and whether people were born in the UK. Of the larger ethnic groups in the UK, people of Indian ethnicity are on average high earners, while people of Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnicity are lower earners on average.

How well off this actually makes people is influenced by where people are. Just under half of people of black ethnicity in England and Wales are in London, where wages but also living costs are higher. About a third of people of Asian ethnicity are in London, and just under 10% of white people.

Fortunately for earnings data at least we can get more granular, and look at nationality.

Via a Freedom of Information request, I have obtained new data on earnings by nationality from the HMRC “Real Time Information” project. We can compare that information to data from survey-based methods like the ONS Annual Population survey (which has a limited sample size, and covers fewer nationalities).

This data is not for all migrants, but only for non-UK nationals (and in the case of the RTI data, those who were not UK nationals when they got their NI number).

Unsurprisingly, there is a correlation between monthly and hourly earnings. The chart below shows those countries where there is data from both RTI and APS sources.

In general, nationals of richer countries earn more (such as Western Europe and the anglosphere countries) and are in the top right. Nationals of poorer countries earn less (like Pakistan, Turkey, and Bangladesh, in the bottom left). There are variations though: on both measures Indian nationals earn much more than people from neighbouring countries.

The new FOI data also lets us look at the earnings distribution within nationals of each country. For example, Australian nationals at the 25th percentile earned more than Bangladeshi nationals at the 75th percentile. UK nationals are more or less smack on the average. While there are more countries with nationals earning above the average, there are larger numbers of people here from the countries whose nationals earn less, which is why the total is shifted to the left.

A more selective approach

Over the long term a large proportion of those who have come to the UK have not been net taxpayers. So existing residents have faced the downsides on housing and the sharing out of the capital stock between more people, without getting the upside of a net tax contribution.

Sadly this is still the case for the new flow of migrants, despite the rhetoric of a “points-based system.”

First, a large proportion of those who moved to the UK over recent years did so for reasons other than work, so avoiding the earnings requirements of the work routes. In fact, out of two million non-EU net arrivals over the last five years, only 15% came principally to work. Even ignoring those on the asylum and humanitarian routes, many others also came without facing salary requirements because they came as students, or adult dependents of students or workers, or for family reasons.

Second, even of those coming via the supposedly more selective work routes, a large proportion are actually coming for low wage work, something I wrote about previously. A huge number of those coming via this route are getting visas to do care work, but that is not the only lower-wage group.

Even of those on skilled worker visas, 68% came to occupations where the median salary for people being sponsored in their occupation was less than the median earnings of full-time workers, and 72% of those on skilled worker visas came to occupations where the median salary was less than the mean earnings of full-time workers:

3) The social effects

Obviously there’s more to life than economics.

Ask normal people about their concerns about migration and a bunch of non-economic concerns come up. Like the value people put on living a settled, rather than transient community; of knowing your neighbours, and so on. Being able to speak easily to one another comes up a lot.

Even in Leicester, a majority-minority city, the churn of further new arrivals can sometimes cause tensions: to give just one example, the role of new arrivals is (rightly or wrongly) often cited as a factor in the recent disturbances.

All these things matter, but they are hard to put numbers on.

However, there is academic work that tries to put numbers on these effects.

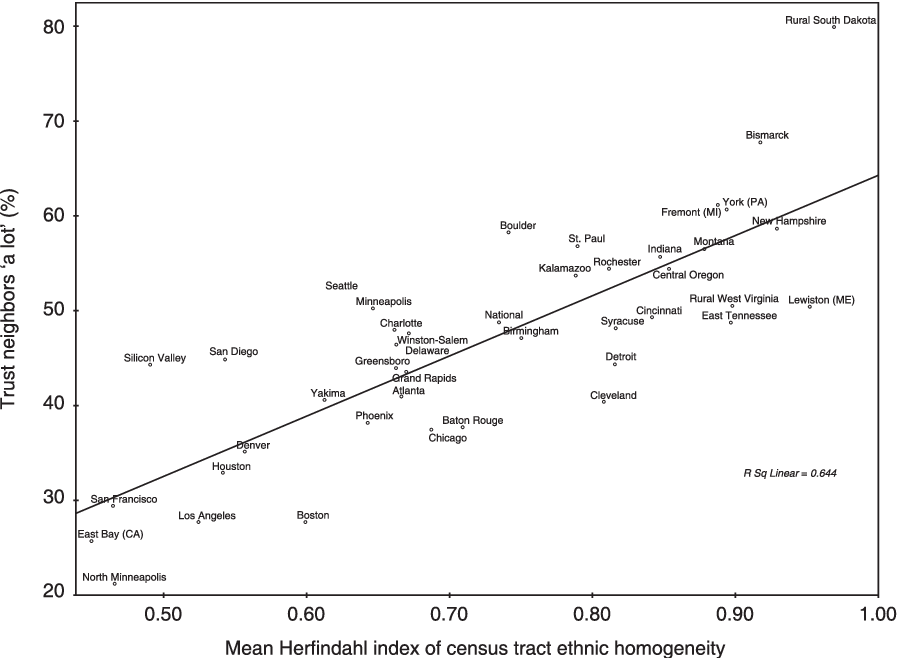

One of the most famous findings in the literature is Robert Putnam’s discovery that in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods: “Trust (even of one's own race) is lower, altruism and community cooperation rarer, friends fewer.” This finding has been replicated by others around the world and seems robust to controlling for various other factors.

A 2020 meta-analysis concludes that: “We find a statistically significant negative relationship between ethnic diversity and social trust across all studies. The relationship is stronger for trust in neighbors and when ethnic diversity is measured more locally.”

The tendency of white British people to cluster together is well documented in successive censuses, and this “white flight” effect was captured by the BBC in a documentary on cockneys in the east end of London. White people are significantly more likely to move to places where the white share of the population is higher than equivalent non-white people are.

But it’s increasingly clear this isn’t just driven by racial intolerance. Eric Kaufmann notes that at least for white people, people’s sense of community is much greater in less diverse areas, with far more people strongly identifying with their neighbourhood on the Home Office’s ‘Citizenship Survey.’ He suggests this may explain why whites with liberal views are roughly as likely to engage in “white flight” as other white people.

Indeed, the same effects may help explain why people across different ethnic groups cluster together strongly. In the 2021 census of England and Wales, just 10% of neighbourhoods (LSOAs) contained 63% of people identifying as of Caribbean ethnicity, and 76% and 79% of people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity respectively.

Quality of life

I started off by saying that what mattered was quality of life, not GDP.

In recent years ONS have had an excellent programme to measure subjective quality of life directly, by asking people questions about their happiness, anxiety, satisfaction and their sense that life is worthwhile. The results are fascinating.

Londoners are not happy, despite having higher incomes than most of the country, even after housing costs.

In fact, even if you control for all the other factors that the ONS measure (their age, sex, class, health etc), Londoners are less happy, more anxious, and less likely to think their life is satisfying or worthwhile.

Controlling for everything else, the satisfaction gap between people living in London and the rural north is pretty close to the gap between being divorced or not.

Our cities are where it all comes together. The effect of migration, the pressures on infrastructure, the social and economic effects and so on.

So it is striking that the least happy places (in red) tend to be urban, dense and diverse (though rural areas that have seen rapid recent migration around the Wash and Fenland are also unhappy).

In contrast, the areas where people are happiest (shown in purple below) tend to be rural.

About a decade ago there was a burst of terrific boosterism about London and other “global cities”. A few academic and cultural things came together and there was a moment where we were being told that our future happiness depended on making more places into swashbuckling, cosmopolitan, here-today-gone-tomorrow global hubs.

That may be good or bad economics, but either way that model certainly doesn’t seem to make people happy.

None of this can prove anything. But if simplistic ‘line-go-up’, GDP-and-immigration-maximising libertarianism was the key to the good life, then the map above would surely look different.

Conclusions

One: we should improve the debate. Discussion about the costs and benefits of migration for existing residents - in so far as it happens at all - tends to focus on just one narrow aspect of one element of the story - are migrants net taxpayers? We need to think more about the wider economic effects on the capital stock and housing. And there are a bunch of considerations about quality of life - considerations that that are more than just economic - which should also guide policy in a more cautious and selective direction.

Two: we should improve the data. The UK needs to do what other countries have done, and get much better, more granular data on all these questions - and data that is about migration, not just ethnicity as too often at present. While HMRC has started producing the data is cite above (in response to FOI requests!) in other ways the data has gone backwards, with DWP ceasing to publish data on welfare claims by nationality in 2021.

Three: we should improve the current migration system. Given the other downsides, we should aim to ensure that a larger share of migrants are people who can make substantial net contributions. Right now the system is so far off track, that at present we could make huge strides just by having a greater proportion of our migration coming via selective routes, applied universally. For example, the review of the Graduate / Deliveroo visa route announced on 4th December hasn’t yet started. There are some basic abuses going on that we should start by fixing: for example, we know from a report for the Home Office that about a quarter of those coming on the social care visa don’t work in social care.

Four: we should consider wider reforms to the system to reflect longer term effects. Even just looking at earnings, I’m struck by how monumentally different economic outcomes are for people coming from different countries. There is no such thing as a ‘typical’ migrant.

But, as we’ve seen, earnings are only one of the factors that determine whether different cohorts of people are likely to make a positive tax contribution in the long term. To pick just one example, people coming from some countries are much more likely to marry and bring over to the UK people who are then less likely to work, which is a major factor in whether those households have a low income.

For many years we had a different set of migration rules for one group of high-income developed countries (the EU) than we did for the rest of the world. One option would be to return to some version of this, and have different rules for higher income / developed countries more generally.

We already have differentiated rules for visas. People from Botswana don’t need them, but people from Namibia do. There’s a map here, and it shows how specific and bespoke the visa system is.

More information generally means more predictive power. While individual considerations like earnings thresholds should take centre stage, if more of the rules were bespoke to different countries we might be more likely to maximise our chances of getting the best out of immigration, while minimising the hassle of immigration controls.

Or… we could just try and make the one-size-fits-all-approach work. But successive governments have struggled to do this.

For example, the last Labour government tried to raise the minimum age to bring a foreign spouse to the UK. They were concerned that in some communities it’s the norm to marry people from back home, often where the spouse is very young and speaks limited English, with a bad effect on integration, and bad economic effects. There have been various tragic cases involving this scenario. However, the Labour government were overruled by courts on ECHR grounds (even though Denmark has more stringent rules and is in the ECHR). A critic of one-size-fits-all might ask: do we really need to have the same rules on family reunification for countries where politicians are not worried about this problem, as the ones where they do?

Another alternative aspect of policy we should consider more is about temporary work versus citizenship. Gaining permanent citizenship in the UK is easier than in several of our neighbours. For example, people cannot gain Danish citizenship if they have claimed benefits in the last two years (or for more than four months in the last five years). People are blocked from citizenship if they have committed serious offences, but even smaller offences punished with a fine will block people from obtaining citizenship for many years afterwards. In contrast, in the UK people are (rightly) astonished that dangerous people are allowed to stay and/or gain citizenship even after committing serious crimes.

The UK has some schemes like the Seasonal Agricultural Worker scheme which are explicitly for a temporary period of work, but in general the gap in requirements between temporary migrants for work and permanent migrants for settlement is smaller than in other countries.

We should add this to the debate. That said, there are loads of things we could do within the current system to increase the benefits and reduce the costs of migration for existing residents. So we should debate wider reforms, but start by fixing the basics.

Hey Neil - some thoughts here (also posted on twitter/x: https://x.com/Isar_b/status/1760240849189740794?s=20)

It's nice to see an MP lay out their thinking in detail, even if I disagree with policy recommendations that come out of it. It allows constituents engaged on the substance in a way that's increasingly infrequent in our fast-moving, short-attention-span news cycle.

On the actual substance of the analysis:

Totally agree on the challenges in data quality, but net fiscal contributions by ethnicity is an unreliable proxy for immigration. Even country of birth data is unreliable, although less so. Selection biases will skew the data here quite substantially. The earnings data quality is much better and so the analysis holds up a lot better.

Second there are deeper questions with the net contribution maths:

Immigrants disproportionately in sectors that have positive externalities (NHS, care roles, high skill sectors). You need to consider vacancies in these sectors - to really calculate the net impact on the economy and the governments fiscal position.

Moreover, the reason for immigrating is not stable. I came to the UK as a dependent (NB: I'm now a citizen) & I know lots who came for education but stayed for high skills jobs. Being thoughtful about the pipeline of talent requires looking beyond original reasons for immigrating

On the recommendations, deeply agree about the chronic underinvestment issue but there are other policy levers to think about - here are just a fewL

1. (Easy win) Helping people work while asylum applications are being processes

2. Building a more effective pipeline of graduates into high skills jobs. This includes more career support and crucially getting better at commercialising research (uk is particularly bad at this esp compared to us)

3. Change how we calculate fiscal contribution so we acknowledge public sector roles' externalities

4. Paying those in the NHS or care sector more (by the nature of these calculations this would make a huge impact to the analysis because they'll be contributing more fiscally)

5. Doing more longitudinal research on dependents to understand lifetime contributions rather than looking at 1 year snapshots and extrapolating without evidence

With respect, your party has been presiding over this for the past 14 years, why are you only just waking up to an issue that the public has been concerned with throughout that period? The migration model used by successive Conservative governments has been of the GDP is the only thing that matters nature, yet it is blindingly obvious the it is GDP per capita that is the better measure of national wealth and health. Throughout the entire tenure of Conservative rule, GDP per capita has largely flatlined (I’d guess that if you had data for GDP per capita for the median wage It may even show a decline). Since the 2019 changes, we are seeing actual falls in GDP per capita, even when those in the upper earnings percentiles are getting 16-20% wage increases. If you took them out of the equation, I suspect the fall would be greater than 0.7%. Put bluntly, Conservative policy is making people poorer.