The grammar school of the western world

Time to think differently about migration

The statistics out today on migration are likely to provoke a lot of debate. This post aims to take a step back.

You don’t need to tell me that immigration can have economic and social benefits. I have many friends and brilliant colleagues who wouldn’t be in the country without it. It’s pretty cool being with someone when they see snow for the first time.

You don’t need to tell me that sometimes people need to seek refuge here. We’ve had refugees sharing our family home, fleeing the war in Ukraine. It was sad and strange to share breakfast with a mother checking her phone to see if her loved ones or home had been hit by rockets overnight.

You don’t need to tell me that people can come here and become fully British. The most anglophile person I know comes from 6,500 miles away.

And yet I think our current immigration policy isn’t right, and too much of the debate we have just misses the point.

What kind of migration

Far too much of the UK debate is ‘for’ or ‘against’ migration rather than about the specifics of what kind of migration on what basis.

My own view is that Britain should aim to be the grammar school of the western world: immigration should be both lower and much more selective.

We live in a world of eight billion people, with ever more on the move, and (sadly) many people living in countries where they are worse off than in Britain. So we have more or less our choice of who to admit.

Although migration obviously does change the culture, this post is going to focus mainly on the economics. I think it is likely that the policy that’s best for the economy also be the best culturally too: highly able and successful people are likely to have more positive cultural impacts.

The scale of the change

The change brought by migration has been really big over quite a short period.

In 2010, David Cameron said:

“In the last decade, net immigration in some years has been sort of 200,000, implying a two million increase over a decade, which I think is too much. We would like to see net immigration in the tens of thousands rather than the hundreds of thousands.”

And yet from June 2012 to June 2023 net migration added 3.3 million to the population, just over 300,000 people a year.

A net 4 million people from other countries came to the UK, and 700,000 British people left.

The gap between what was promised, and what has been delivered is so corrosive to democracy. People voted to reduce (not just control) immigration in multiple elections and it was also an important motive for many leave voters in the referendum.

However, the system Boris Johnson put in place after Brexit has led to much higher immigration overall, with more coming from relatively poor developing countries. This is not what people voted for.

While some Twitter commentators find this very amusing, I think it is putting a bomb under our democracy and risking the emergence of the kinds of far right parties we see gaining ground all over Europe.

A friend in politics once told me they didn’t think migration had changed the country. That depends where you live! In large parts of the country migration has changed many aspects of life, over quite a short timescale.

Here is data from the census in 2001 and 2021, showing what proportion of people described themselves as White British in each place in both years.

That’s obviously affected directly by migration and also by the demographics of those who have come. The third image shows census 2021 data just for the under 45s - in a sense that shows how the population will change in future even without any further migration.

The number of majority-minority areas (red and orange below) has grown rapidly, particularly in urban areas:

Onto the economics

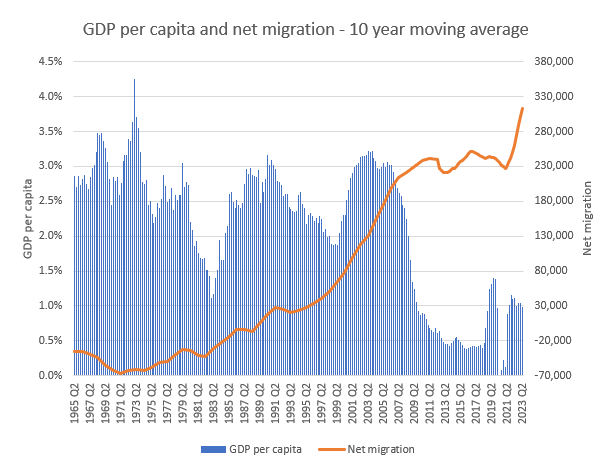

So having lodged my point about the scale of the change, onto the economics. Many people just assume that all migration must be like magic rocket fuel for the economy. That’s not at all obvious. Recent very high levels of immigration have actually coincided with lower productivity growth.

Some of the main economic effects of migration are below.

Migrants bring their own skills and ideas. Some are highly able and will be net taxpayers, which will benefit existing residents. Others may not work, or work at a level that means they will likely take more out in public spending than they pay in tax, which will cost existing residents.

Migrants sadly don’t bring their own housing or land or infrastructure, meaning the stock of these things built up over long periods is shared out among more people. This is a cost to existing residents. Housing is less affordable, while infrastructure from roads to GP surgeries becomes more congested and productivity is lower.

The national debt is shared between more people. Whether this is benefit or cost to existing residents depends on whether they are going to be net recipients or net contributors as above.

The movement of people may have a role to play in the movement of ideas, though this doesn’t necessarily have to mean permanent migration.

In this piece I will look at just the first two, and look just at housing as an example of what happens when the capital stock is divided between more people.

1) Net contributors or not?

The Oxford Migration Observatory has a good summary of some of the studies which attempt to work out whether or not people who come are net contributors or not. They note that:

“The fiscal impact of migration to the UK is small… Studies examining the fiscal impact of migrants have produced different results, although in all cases, the impacts have been estimated at less than +1% or -1% of GDP.”

That is kinda boring, but is itself significant: there are people in the debate who think the net effect is disastrous or that the country will explode if net migration drops below 500,000 a year. Neither is true.

They also note that studies consistently find that: “the fiscal impact of EEA migrants is more positive than that of non-EEA migrants.”

Every study cited shows that non-European migrants are net recipients, while some studies show European migrants as contributors while others suggest they are net recipients.

This is significant as the UK has shifted sharply in the direction of non-European immigration under the new system, as noted above.

The Office for Budget Responsibility has shifted its assumptions about the economic effect for this reason. The March 2023 Economic and Fiscal Outlook noted that:

“It is therefore likely that the participation rate of migrants under the post-Brexit regime will be lower than in the past, so we have assumed they will have the same participation rate as the resident population.”

There has been a lot of focus on whether the overall effect of migration is net positive or net negative for the exchequer.

That’s interesting, but not the real question. Migrants from the EU or rest of the world will contain a mix of people: from those who will be major net contributors to major net recipients. You can debate whether the median migrant is or isn’t a net recipient, but from a policy point of view the right thing is to be more selective, so that you reduce the number of recipients and so make the balance more favourable overall.

You might think the current balance is more like A or B below, but either way you want to have a more selective approach, so you can reduce the size of the red triangle and so make the net effect more beneficial.

Whether you will be a net contributor to the exchequer depends on many things: your earnings, health, age, whether you have kids or dependent adults…

Other countries are able to set migration policy armed with a much richer understanding of these issues. Denmark produces analysis like the below, broken down by country of origin and what point people are at in the life cycle.

Sadly, while the UK government does produce figures on the amount of income tax paid by people from different countries, it doesn’t produce figures on net contributions (all tax in, vs all spend out).

Just looking at tax paid, the variations are massive. To look at just one dimension, the variation by country of origin is below: people from Western Europe and developed English speaking countries pay a lot more in. And of course where people are coming from is just one part of the story: for any country the route people are coming under and their skills and earnings all obviously matter.

ONS do attempt to work out how many people who are net recipients across the whole population in the Effects of Taxes and Benefits. In 2021 54% of individuals received more in benefits than they paid in taxes, in 2022 it was 53%, though the trend has been that more and more people are net recipients - see chart below:

So it would not be surprising if a large proportion of migrants were net recipients, but unlike the current population we have a choice about who to admit: we can aim to select for those more likely to be contributors. There are numerous rules and thresholds in the system we can use to do this.

But our system is not very selective. As Jonathan Portes notes: “Our immigration system for work and students is possibly the most ‘liberal’ of any advanced economy, with fully half of all jobs in the UK labour market open in principle to anyone from anywhere in the world”.

With no caps, the new system automatically becomes more liberal over time: earnings thresholds aren’t uprated with inflation. High inflation means more lower wage jobs are opened to the world, increasing immigration further.

And that’s just the work route. The government has done a number of things that have shifted the balance towards people who are less likely to be net contributors, including on the family and student routes.

As Nick Timothy notes:

The definition of “skilled work” was watered down, and work permits made available in unlimited numbers. The shortage occupation list was extended to allow the recruitment of more and more foreign workers. Employers are no longer required to seek workers resident in Britain before recruiting from overseas. The salary threshold, supposedly set to ensure high-skilled immigration, is now £26,200 and for some workers only £20,960 – literally minimum wage levels.

At the new National Living Wage level from April 2024, someone working 40 hours a week 52 weeks a year would actually earn £23,795. Timothy also notes that:

Under Johnson, foreign students, regardless of their field of study, were given the automatic right to stay and work in Britain for two years at the end of their courses. The joint income requirement to sponsor a spouse for a family visa remained frozen at the level first set – £18,600 – in 2012. The rules setting out how migrants may bring dependants were dramatically liberalised: some applicants for a work visa need to show they have as little as £285 per dependant in the bank.

To that list it is worth adding the creation and expansion of the social care visa. This has been one of the fastest growing routes and acts as an alternative to increasing social care funding and wages. There is an ever-growing pile of reports of exploitation of this route with a 600% increase in reports of modern slavery in the sector last year.

The people coming are, I’m sure, good people coming to do an important job.

I’m criticising the policy, not them.

But the social care visa is a piece of pure Treasury short termism. In order to hold down costs and spend in the short term we are importing a lot of people who are likely to be net recipients of taxpayer funds in the long term.

Lower spend today, but higher spend long term.

As noted above, you have to be a fair way up the earnings scale to be a net taxpayer, even while you are of working age. Sadly, most people in social care are right at the bottom of the earning scale, indeed, the overwhelming majority are paid close to the legal minimum.

According to Skills for Care, the month before the new rate of the National Living Wage came into effect in April 2023, 55% of independent sector care workers were being paid below the new minimum. The median care worker pay in March 2023 (£10.11) was just above the 10th percentile of the national earnings distribution.

Given this, it is inevitable that large numbers of the people coming under the social care visa will be net recipients not net taxpayers. And of course a large proportion of people coming through this route will stay and become pensioners here. The Treasury is effectively opting to pay less now, but more later.

It is absolutely not the case that “we can’t get British people to do these jobs for any money”.

When I was (briefly) the Social Care minister I was struck by how responsive to slight variations in pay people are. Because they are so low-paid people will move jobs within care for a small increase. A new Amazon warehouse locally can spell trouble for the local care sector.

Sadly, social care is not the only example of short-termism. Too often migration policy is driven by corporate and departmental lobbying to address the needs of the moment with no strategic consideration of people’s long term contribution or any sense of a budget constraint or trade offs between groups.

That’s one reason I think it’s essential to create an ‘OBR for migration’.

2) Pressures on infrastructure and housing

While migrants can bring their skills to the UK, they cannot bring with them a house, a mile of motorway, a load of railway track, a chunk of a university or a new GP’s surgery.

People who come may be net taxpayers or net recipients, but more people inevitably means diluting the capital stock between more people.

Housing is maybe the most salient example. Some people who are otherwise sensible want to wish away this problem, and say we can ‘simply build absolutely loads more houses’.

While we can and should improve housing supply, to think we can add people at recent rates and simultaneously solve the housing crisis is absolute magical thinking and shows people don’t understand the issues (sorry!).

The chart below shows the rate of new housebuilding in England and Wales compared to total population growth and, of which, how much of that is net migration (England and Wales get about 94% migrants to the UK).

The growth in the housing stock has been remarkably constant over 50 years. The economic cycle goes up and down, governments come and go, but the blue line remains in a fairly narrow range. What has radically changed is the growth of the population. And that is overwhelmingly driven by net migration.

Over the last decade about two thirds of increase in the population has been directly from net migration, and the share is rising: even before last years spike, in the three years to mid 2022, net migration accounted for 87% of population growth. It accounts for 84 per cent of projected growth.

As everyone knows, the ratio of the median house price to median full-time earnings has deteriorated over the same period in which net migration has been high - from 3.5 times earnings to 8.3 times. Rents have followed, though the relationship is loose.

Some admit this is a challenge, but assume we can just defy history and build so many more homes that we both undo the decline in affordability and offset the effect of all the extra migration? Sadly, this is unrealistic.

One of the most heartbreaking moments I ever had in government was being walked through (then) DCLG projections of how much difference changes in supply make to affordability. It’s super depressing.

Because the stock is big relative to new supply, and because many other factors (rising incomes etc) also matter, no remotely plausible increase in supply is going to improve affordability without also taking action on the demand side, including reducing net migration.

In 2018 DCLG published its rule of thumb model, “Analysis of the determinants of house price changes”.

It says that (ignoring incomes, interest rates etc)

1% growth in households increases house prices 2%

1% increase in total housing stock reduces house prices 2%.

So every 1% increase in the population needs to be offset with a 1% increase in the housing stock (pretty intuitive). But affordability will still deteriorate if you just build enough for the new arrivals, not least because incomes are going up, pushing up prices.

From June 2012 to June 2023 net migration added 3.3 million to the population of England and Wales, roughly a 6% increase, therefore adding 12% to house prices on CLG’s ready reckoner.

In England and Wales from 2012 to 2022 (sorry no figs for ‘23 yet) the housing stock grew eight and a bit percent (pushing prices down 17%). So net migration is eating up most of the benefits of supply - and that’s before we even get to the upward pressure on prices from domestic population growth or rising incomes or more fancy factors that DCLG’s model doesn’t capture, like growing desire for space, shrinking unit sizes etc..

Net migration obviously isn’t the only factor, but if we are to improve affordability then having high net migration effectively means you have to run a marathon to even get to the starting line of the race.

As I have written about before, we obviously need to take other actions: increase supply, use tax to cut demand, incentivise investment demand to flow to more productive uses, reset housing inflation expectations etc.

But people who say '“yeah but build more houses and problem go away” don’t have a sense of how hard the housing problem is to fix.

It’s like a guy with pipe cleaner arms turning up at the gym for the first time ever and announcing they can lift a tonne weight no problem. It’s magical thinking.

Nor is it just those who want to rent or buy privately that are affected. People are surprised to lean that 48% of households in social housing in London are headed by someone not born in the UK. Many of these people have subsequently got naturalisation, but that is little consolation to someone else who now can’t have that home.

Conclusion

I think there are lots of assumptions in the UK debate on migration that are not right and a lot of wishful thinking. I will come back to some of the other effects and arguments of migration in future posts.

But thank you for reading!

As someone personally not inclined towards the Tories, I still very much enjoyed the article and thought there were are lot of valid points made, well proven with underlying data. However, I think there was one major effect missed, and that's probably the biggest of all: The effect of migration on age distribution and the way it alleviates fiscal pressure. Migrants to the UK, especially those coming down the graduate route, are mostly young adults. That means they spent a much higher proportion of their time in the UK in the workforce compared to the average native (who also spends his childhood here). Obviously, if one would cut off migration at some point, that would mean earlier migrants get old and at some point become net recipients, nullifying the effect. This is probably what the studies on the net fiscal effect of migration find. But as long as there is continued migration, it boosts the share of people in the workforce and that means it gets a lot easier to pay for state services and caring for pensioners and kids. Overall still a very good analysis, though!