The Deliveroo Visa scandal

The growth of policies that deliberately encourage low wage immigration

Welcome to the data desert

How many people from different countries are in the UK right now? How many of those who have come to the UK from different countries are in work? What do they do, and how much do they earn? What does it look like if you break it down by age, or qualifications, or the legal route by which people came here?

These are the sorts of basic questions we need to be able to answer to make sensible immigration policy decisions.

They seem like questions it should be pretty easy to find answers to.

Nope.

Other than the last census, we don’t have up to date estimates of how many non-UK nationals are in the country. Nor does ONS publish annual estimates of migration by individual nationality, apart from for five countries.

What about when people have come explicitly for a job, and there is some kind of legal salary threshold they are required to be earning in order to get a visa: surely we can see the earnings data for those people, at least?

Wrong! The Home Office must (in theory) be collecting it, but it says it doesn’t publish it: “The Home Office does not publish the information on the salary of work routes.”

There are disjointed bits and pieces of data out there. In response to Freedom of Information requests, HMRC has published some data on how many non-UK nationals are in payroll employment, and their median earnings. However, the only breakdown is by EU and non-EU nationals.

I have concerns about this data, which includes non-residents. But for what it is worth, it suggests that although the gap narrowed, all recent cohorts of non-EU migrants earn less than established UK workers. 2021 arrivals earned £500 less per month in their second year here, while even 2014 arrivals still haven't caught up.

We can try and get data on employment rates by individual nationality, from the Labour Force Survey, but there are problems because of its limited and falling sample size.

We can get some better data from the census on employment by country of birth. But only once every ten years. And we can’t see from the census how much people are earning, or by which legal route they came to the UK. Still, we can at least see from it the massive variation, which helps to move the discussion on from the terrible “is immigration good or bad” framing we too often seem trapped in, towards more sensible questions like: “immigration of who, under what circumstances?”

Source: Census 2021

One of the most urgent policy priorities for government (which hopefully most people involved in the debate would agree on), should be to start linking up different datasets so we can have a better quality debate about the pros and cons of different types of migration, as other countries do.

I mention all this by way of a very lengthy preamble, because the data desert is the context to the Deliveroo Visa scandal.

Holed below the waterline

In previous pieces I have made the case for lower and more selective migration - to make the UK the grammar school of the western world.

Many migrants do not come primarily to work. Non-EU net migration to the UK over the last 5 years was 2,008,000. ONS broke this down as follows:

309,000 work (15%)

269,000 work dependents

450,000 study

133,000 study dependents

230,000 family

88,000 other

269,000 asylum

226,000 Hong Kong and Ukraine humanitarian

34,000 other humanitarian

Given this, we would ideally ensure that migration for work selects for the best and brightest, and those most likely to be net contributors.

But in recent years two migration policies have punched massive holes in attempts to make the system selective, and have instead allowed people to come and do low wage work.

Unsurprisingly, these people tend to come from low income countries: for people in poorer countries the opportunity to be a low earner in the UK still provides the opportunity to earn more than they can at home. In many cases they will send funds home: hence the London Underground carries many adverts for money transfer firms.

Let me be clear at the start that I am not criticising or blaming them: I am criticising the policy.

The sort of work people often end up doing in this situation has led to them being dubbed ‘Deliveroo Visas’. It is probably unfair to single out one particular employer, but the UK has many opportunities to work in the grey economy for low wages.

The two biggest recent drivers of low wage migration are the two year student work visa, and the social care visa.

Graduate work visas: a disaster we were warned about

In 2019 Boris' Johnson’s new government decided to re-introduce the two year post study work visa, which had been abolished by the Conservative/Lib Dem Coalition government.

The government press release a the time hailed it as a move which would “help recruit and retain the best and brightest global talent, as well as opening up opportunities for future breakthroughs in science, technology and research.”

As well as being able to work while they are students, the graduate route enables people to work afterwards at any salary threshold, any skill level, and stay in the UK to look for work without any sponsor.

In other words, it allows holders to circumvent all the salary and other requirements of the normal work visa routes, which are supposedly there to make migration a bit more selective, so more beneficial.

The Migration Advisory Committee’s most recent annual report is scathing about the effect this has had.

When a group of mild-mannered, fairly liberal academic types think you’ve gone too far in liberalising immigration, you probably have.

The MAC start by pointing out that they did warn against this:

In our 2018 report, we recommended against the introduction of a separate graduate visa, due to concerns that it would lead to an increase in low-wage migration and universities marketing themselves on post-study employment potential rather than educational quality. As we put it at the time:

“If students had unrestricted rights to work in the UK for two years after graduation there would potentially be demand for degrees (especially short Master’s degrees) based not just on the value of the qualification and the opportunity to obtain a graduate level job and settle in the UK, but for the temporary right to work in the UK that studying brings. A post- study work regime could become a pre-work study regime.”

And it turns out the MAC were quite right: restoring the right to work after graduation with no salary threshold has punched a hole in attempts to make migration more selective.

Having abolished this route under the coalition, the effect of turning it off and then on again can be seen very clearly: it’s had no effect on the numbers coming from rich countries, but has made a huge difference to the numbers coming from poorer countries.

Source: Home Office Immigration statistics, Vis_02

The MAC report also totally smashes the idea that this policy has anything to do with the ‘best and brightest’:

“Our recommendation [against it] was influenced by evidence at the time showing that the earnings of some graduates who remained in the UK after graduation were surprisingly low, especially for some Master’s students, suggesting that those who would benefit most from a longer period to find a job would not be the most highly skilled. LEO data showed a lower quartile wage for non-EU postgraduate taught Master’s students 1 year after study of £15,400 in 2015-16 (compared to £20,500 for domestic students).”

They note that the growth in international students:

“has been fastest in less selective and lower cost universities. The rise in the share of dependants is also consistent with this. Since both the applicant and an adult dependant can work both during the original study period (students can work up to 20 hours per week during term and full-time outside term), and for 2 years on the graduate visa, the cost-benefit of enrolling in a degree has changed substantially. In the case of an international student studying a 1-year postgraduate Master’s, and bringing an adult dependant, the couple could earn in the region of £115,000 on the minimum wage during the course of their 3 years in the UK. Some universities offer courses at a cost of around £5,000.”

They conclude that:

“This data suggests that the graduate route may not be attracting the global talent anticipated, with many students likely entering low-wage roles”

And:

“If the objective is to attract talented students who will subsequently work in high-skilled graduate jobs, then we are sceptical that it adds much to the Skilled Worker route which was already available to switch into after graduation, and we expect that at least a significant fraction of the graduate route will comprise low-wage workers. For these migrants, it is in many ways a bespoke youth mobility scheme”

The MAC also note the rising number of students who bring (adult) dependents with them:

“the number of dependants coming to the UK under student visas has increased significantly, and at a much faster pace than the rise in total student numbers, as illustrated in Figure 3.12. Dependants accounted for 148,000 visas in 2022, 24% of all student visas. The majority of dependants are adults”

“This increase in student dependant visas has largely been driven by applicants from 2 countries: India and Nigeria. In 2015, these 2 countries accounted for only 11% of dependants, at around 1,500 individuals in total. By 2022, they accounted for 73% of dependants (Figure 3.14) - over 100,000 individuals in total. In 2022, the ratio of dependants to main applicants exceeded 1 for Nigerian nationals (Figure 3.15) - this is 10 times the rate for all other countries (excluding India).”

The MAC note that

“We do not currently have data that allow us to know whether adult dependants are working in the UK and, if so, their earnings.

So, the route sold to voters as attracting the “best and brightest” has, in fact, led to many entering low wage roles in the Deliveroo economy.

Universities challenged

But what about the effect on universities? Defenders of the policy sometimes suggest that it is a way of boosting UK higher education. But the growth in international student numbers has been concentrated in the cheapest universities with the lowest entry requirements. As the MAC point out:

“Figure 3.8 highlights that since our last report on international students in 2018, the growth of international students studying taught postgraduate degrees has predominantly been in institutions that charge the lowest fees (bottom quartile of the fee distribution). This lowest-fee quartile accounted for 13% of international postgraduate students in 2018/19, compared to 32% in 2021/22.”

“Similarly, growth in international postgraduate students has been strongest at the less selective universities. We can proxy the admissions selectivity of a university by using the average UCAS tariff points required for entry. Higher tariffs mean higher grades are required for the course… Figure 3.9 shows that since 2018/19 there has been much faster growth of international students studying taught postgraduate courses in institutions with lower average UCAS tariffs.”

Predictably, if we look at the individual universities that have seen the largest percentage growth in their international students, most of it is accounted for by students coming from the poorer countries and regions which have driven growth overall. Neither students from China or from rich countries are driving their expansion:

Source: HESA Table 28 - Non-UK HE students by HE provider and country of domicile. UCLAN also saw significant growth in numbers from Nepal, Ulster from the Philippines, and Suffolk from Romania.)

Students from overseas are generally more profitable for universities than UK students, because fees are uncapped and higher.

But is fuelling the growth of lower tariff, less research-intensive universities really worth the cost of punching a huge hole in our attempts to have a selective immigration system?

Much of the fee income will go on the student themselves. It may be that universities are able to make some small profit on their international students. But does this profit translate into an economic benefit for the UK via high quality research which enhances UK productivity, or is it absorbed by the universities on activities which don’t really do this? As Alan Manning has pointed out:

“this is a very indirect way of funding research because most of the extra students are likely to go to less research-intensive institutions. An alternative would be for the government to sell work permits directly and then use the proceeds to fund the research deemed most important.”

Compared to people coming to earn more than the skilled work threshold, these migrants are much less likely to be a net economic benefit, and if we had an immigration budget constraint, it would make much more sense to prioritise the skilled workers.

Do the extra students at least help bring spending power to poorer parts of the UK? even that is not so obvious.

The Times had a brilliant piece on the growth of universities from the rest of the UK opening London campuses to attract international students:

Universities are alos now spending serious cash on overseas recruitment agents. The Guardian reported that:

“the University of Greenwich paid education agents more than £28.7m in 2022/ 23 – up from £18.3m in 2021/22 and £3.3m in 2017/18. The money went to 230 agencies and related to recruitment of 2,986 postgraduates and 500 undergraduates over the year.. The figures suggest the London university paid an average of £8,235 in agent fees per student.”

Many international students benefitting from the new route do not actually finish their course. Former Universities Minister Jo Johnson recently warned that “entirely unacceptable” dropout rates among Indian and Bangladeshi students of “approaching 25 per cent” was damaging the sector’s reputation.

The government is moving to remove the ability for international students to switch out of the student route into work routes before their studies have been completed (it is not clear why this was allowed in the first place).

But in truth, controlling low wage work by people on student visas is extremely difficult. In theory the rules say students should now work more than 20 hours per week work during term-time. But enforcement of this is obviously nigh-on impossible.

Study and stay

We can’t yet know what the two year post study work visa will mean in terms of the numbers who will stay on in the UK longer term - it is likely to dramatically increase it. After five years living in the UK people can get Indefinite Leave to Remain, and then move on to gain citizenship. The years as a student don’t typically count for 5 year ILR but do count towards 10 year long residence ILR.

If we look at the cohort of students who came between 2007 and 2016 we see that stay rates are (unsurprisingly) higher for students coming from the poorer countries, towards which student migration has now swung.

Looking at the largest countries of student origin, we see that even though there were more students from the US than Pakistan over the period, four times more students of Pakistani origin from that cohort were still in the UK in 2022 compared to Americans.

Only about 6% of students from the US were still here in with valid leave in 2022, but it was over a quarter for countries like Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Of former students from these countries, among those who remaining legally, around half had settlement or citizenship by 2022. Of students who entered from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka during the period, 1%, 2% and 4% respectively had successfully claimed asylum by 2022.

These figures obviously do not include those who come as students and illegally overstay, the subject of a recent Sky News report.

Source: Home Office, Migrant Journey, MJ_D01

So people can come, bring adult dependents and children, work from the off, earn more than the cost of the degree even on the minimum wage, and then in many cases remain in the UK for good.

As the MAC conclude: “the original motivation that the government had for the introduction of the route is unlikely to be met.”

The government has promised a MAC-led review of this policy at some point next year, but are giving no details on when this will be complete.

The “Shortage Occupation List”

Apart from the Graduate / Deliveroo Visa, the other big hole in attempts to make migration for work more selective is the Shortage Occupation List (SOL). This allows people to come to take up jobs where their earnings will be lower than the general skilled worker salary threshold: in some cases much less.

There’s one list for health roles where you have to be paid on the national pay scale, and another for private sector roles.

As noted above, the Home Office won’t say how much people who came on this route actually earned.

But we can look at what the earnings thresholds were for different private sector shortage occupations, and compare those thresholds compared to median earnings in those jobs.

The whole purpose of the SOL is to set going rates below the industry norm, though there is a lot of variation between the thresholds and the medians recorded in the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), and ASHE doesnt have figures for every category.

But it is clear that the SOL thresholds let people come to the UK even if they are earning quite a lot below the median salary in that occupation:

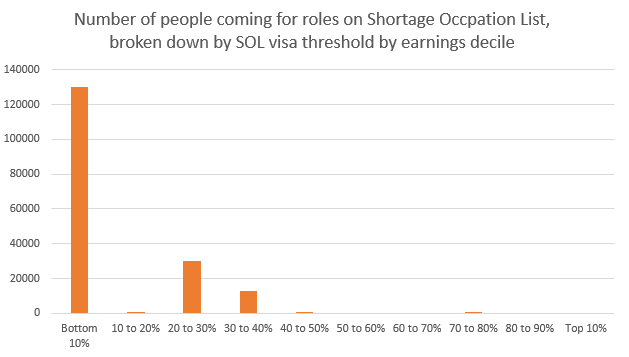

We can also look at how many people came under each of these occupation codes.

Some of the categories are rather odd. Is the UK really short of artists? But the number of artists coming is small.

Overall, the numbers are dominated by care workers, for which the minimum pay threshold is £10.75 per hour.

Again, we don’t know how much people coming on different shortage routes actually earn, because of the Home Office won’t say.

But if we assume that people came for jobs at the threshold for their respective roles, the chart below shows how people coming for SOL eligible roles would have fitted into the UK earnings distribution in 2023.

Overwhelmingly, they would have been at the bottom end:

Source: Home Office Immigration Statistics, Occ_D02, visas granted from Q1 2021 to Q3 2023, Private Sector Shortage Occupation List and ASHE, Table 14.5a, median earnings of all workers

The existence of the SOL is one reason why the government predicts that it’s proposed increase to the general threshold for skilled workers will make so little difference to immigration: only a reduction of around 15,000.

This very limited impact is because the Shortage Occupation List and other routes provide a way around the general threshold, and enable people to come for low skilled, low-wage work.

I have written about the Social Care visa before. People are increasingly aware of the abuse of it. The MAC annual report notes that:

“Unseen UK indicated that there were over 700 potential cases of modern slavery in the care sector in 2022 (though they use a less stringent definition compared to the Modern Slavery Act). This accounted for 18% of all potential victims raised through its helpline.”

UKVI have seen numerous examples of bonded labour linked to the adult social care sector […] One individual had paid £8,000 directly to the sponsor for rent upfront and another had paid £21,000 to their sponsor for the visa. There have been other cases where migrants have had to spend large sums of money, sometimes in excess of £25,000, to ‘agents’ who forge documentation so they can obtain a H&CW visa.”

Again, I am not criticising people in the social care sector, but policy.

As well as poor conditions and bonded labour in the sector, the social care visa is being used as a route into the UK by people who do not then work in the social care sector. As the MAC note:

“Border Force queried the documentation of a migrant who was sponsored by one care provider, who had had 498 visas granted since May 2022. CQC confirmed that this care provider had been dormant since September 2021 and was no longer providing any services. […] UKVI stated that 5 sponsor licences in the care sector had been revoked in May 2023, who between them had made over 1,100 main applicant visa applications.

Assessing the total scale of the compliance problems in the care worker route is a challenge, although the number of cases that have been detected suggests that misuse is a significant problem and greater than in other immigration routes and occupations”

Where people are abusing the care visa, they are likely to end up in other forms of low wage work.

You have to be a fair way up the earnings scale to be a net taxpayer, even while you are of working age. Sadly, most people in social care are right at the bottom of the earning scale, indeed, the overwhelming majority are paid close to the legal minimum.

Given this, it is inevitable that large numbers of the people coming under the social care visa will be net recipients not net taxpayers. And of course a large proportion of people coming through this route will stay and become pensioners here. The Treasury is effectively opting to pay less now, but more later.

It is absolutely not the case that “we can’t get British people to do these jobs for any money”. In fact, eight out of ten care workers are UK nationals.

What it does is support a low wage equilibrium. The MAC does a good job of showing the connection between the use of the care visa and the competitiveness of social care pay in different places:

The MAC quite rightly say:

“the underlying cause of these workforce difficulties is the underfunding of the social care sector. We recommended the addition of care workers to the H&CW visa as part of a package of 19 other recommendations. We were clear that immigration could not solve these workforce issues alone. Our main recommendation was to introduce a minimum rate of pay, initially at £1 per hour above the National Living Wage (NLW), for care workers in England where care was being provided by public funds, to help tackle the workforce issues faced by the sector in the medium to longer term.”

They are right. I don’t know if a pound increase is the right figure (people in social care will move jobs for very little, because they are so poorly paid), but the social care visa is a false economy in the long run: people arriving to do minimum wage jobs are unlikely to be net contributors in the long run.

Fixing this problem with higher social care wages and higher funding would have a cost in the short run, but would likely save taxpayers money in the longer run.

Conclusion

In every election since 1992 the winning party has promised to tightened migration controls.

For a generation at least, politicians have paid lip service to the idea of more selective migration: “we’ll have higher wage, higher skilled immigration”.

But in practice migration has surged to ever higher and now record levels, driven in recent years by short-termist policies which deliberately increase low skill low wage migration.

Rishi Sunak shows far too little urgency in fixing this, and Keir Starmer certainly wouldn’t.

I’m not surprised voters are unhappy.

I do not agree with a lot of government policy on migration eg the nonsense on illegal migration and asylum seekers, but this piece is well argues and thought through highlighting legal migration is the issue in reality. Policy based n evidence and data is always better than policy based on politics

Great article. It's clear as day that many universities are simply selling a backdoor to a working visa and a path to citizenship, it's outrageous and must be stopped. Furthermore the fact that a nominally Conservative government enabled this, against, as you say, the advice of a bunch of left wing academics on the MAC is flabbergasting, or would be to anyone not already familiarised with the mendacity of Boris Johnson.