Following up on 'the costs and benefits of migration for existing residents'

My piece the other day on the costs and benefits of migration for existing residents has prompted a few follow-ups. I’ll respond under two headings.

1) Housing

The Times ran a piece today on the housing impact of migration.

I’d argued that with 67% of private rented households in London headed by someone born overseas, it’s silly to say migration is irrelevant to London’s housing challenges. Migrants are not “to blame” for the origin of these problems. But for the UK, the effect of very high levels of migration adds to our long-running housing problem.

I pointed out that the stock of housing in London grew 10.7% over the decade 2011-21, but that 16.6% of London’s population in 2021 had arrived from overseas over that decade.

Ben Ansell makes the argument in the Times that “migration may matter at the margins but it is low down the list of explanations” for high housing costs.

Ben is not wrong that housing costs are driven by multiple factors. The Government’s own longstanding model for house prices (which is based on the work of academics like Geoff Meen) has multiple factors and says that:

1% growth in households increases house prices 2%

1% increase in total housing stock reduces house prices 2%.

1% growth in real incomes increases prices 2%

1% increase in interest rates reduces house prices 3%

All governments want to increase incomes, and overall interest rates are set by the Bank to control inflation, so those last two aren’t really housing policy tools. Nor does the UK control emigration of British citizens.

Is migration really trivial here? Given that 16.6% of Londoners arrived over the decade, if we assume that migration increased the number of the number of households by a roughly similar amount compared to a counterfactual with other things equal1, then on the model above you’d be looking at migration having added 33% to house prices in the capital over just one decade, or about 15% for England as a whole.

You can regard these numbers as big or small if you like. They probably seem quite big if you are trying to scrape up money for your first house, while paying lots in rent.

And in terms of housing policy levers the government actually has any control over, I’m not sure migration is really that “low down the list”.

Ben Ansell suggests reducing demand from buy to let, and I agree - in fact I was a Spad at the Treasury when the then Chancellor reformed taxes in 2015 to do just this, and it has had a positive effect, helping to halt the collapse of home ownership:

But a report for the last Labour government estimated that over the decade of explosive buy to let growth - the period from its invention in the late 1990s to the financial crisis - buy to let had increased house prices by 7%.

So is the impact of migration really “small” compared to buy to let?

Because growth in real incomes increases house prices, we need housing growth to strongly outrun overall population growth to improve affordability, other things equal.

Somehow there are still people who think the a constant ratio of households to houses would mean no there would be housing problem (and that’s before we even get to household formation being obviously influenced by housing costs).

The government’s house price model quoted above tells you that if the growth in houses only matches the growth of households then prices go up because of rising incomes (and this isn’t just true of the UK by the way).

Because of high rates of immigration, housing growth is not strongly outrunning population growth. In England as a whole over 2011 to 2021 we saw 8.5% growth in homes, but 7.4% of the population arrived over the decade. So migration on its own before any natural population increase nearly cancelled out the impact of new supply.

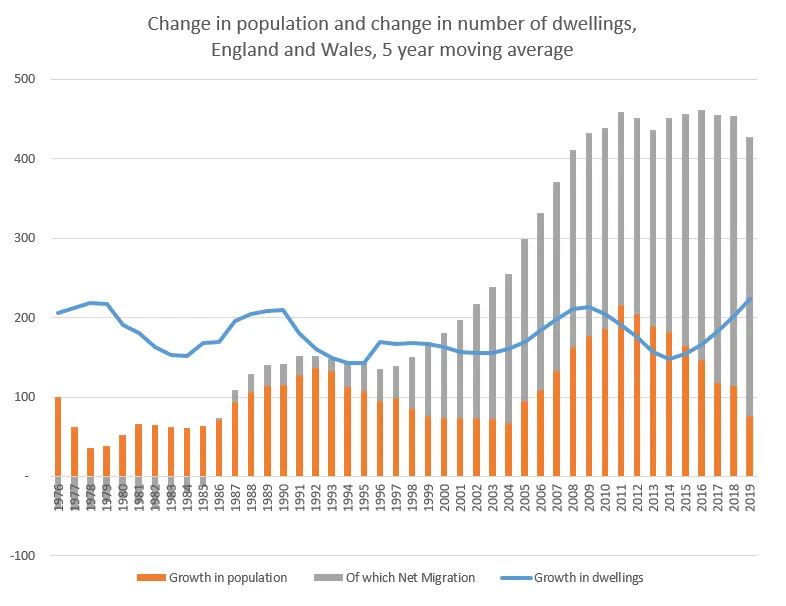

And in London supply hasn’t even kept up with migration alone. Yes, supply needs to be increase, but we have to be real about this as a miracle solution - the rate of housing growth has been in a narrow range for a long time:

I’ve previously argued that we need to do pretty much everything on housing - both measures to increase supply, but also measures to reduce demand.

The demand side measures can also include things on tax treatment, and also structural measures to reset inflation expectations and so reduce the motive to buy housing as an investment asset, rather than making more productive investments in firms.

Given that we basically need to do everything, reducing less beneficial migration should definitely be on the table. Compared to the other policy levers government has in housing policy, reducing migration it is a non-trivial one.

2) Earnings and employment

Jonathan Portes responded to the new FOI data I presented on earnings by nationality (chart reproduced below).

“Neil has previously argued that the very rapid growth in migration from "poor countries" would push down migrant average earnings. My earlier research found no evidence of that as yet, and Neil's new data backs that up… Once again Neil is to be commended for taking data/evidence seriously, and publishing it, even when it doesn't confirm his earlier claims.”

We may be talking at cross purposes. My argument is that growing numbers of people coming from poorer countries (whose earnings are generally, but not always, lower) will tend to push down average earnings compared to what they could have been. If we were more selective we could make the average impact much more positive.

Given the costs in terms of capital dilution, housing market pressures and other social costs, we should aim to make sure that migrants are strong net taxpayers, not just neutral.

To achieve that we would ideally see a large earnings premium, not least because census data shows employment rates are lower for those not born in the UK, and unemployment rates are also higher.

Has the new points-based system had this effect? So far the earnings of overseas nationals overall still look similar to UK nationals. The total and the median for UK nationals are still tracking one another.

So why haven’t earnings for overseas nationals they rocketed up, given the rhetoric around the “points-based system” that was supposedly going to reduce low skill migration?

Part of the answer is that the new system represented a tightening of the rules for EU nationals, but made the rules much less selective for non-EU nationals.

To explain what I mean, here is some more new ONS data on changing numbers of employments by nationality since the new migration system came in at the end of 2020. This comes from a second FOI request I made.

At the moment the data on employments by nationality only goes up to the end of 2022, and HMRC say more recent data will become available at the end of March.

I have tabulated the change in employment numbers 2020-2022 against median earnings by nationality in December 2022:

There is a massive scatter. Some of the nationalities with the fastest growth in employments are mid-table in terms of median earnings, like India and Nigeria. But quite a lot of the faster growing nationality groups have been among those with lower earnings.

Contra to some people’s presentation of the new “points based system”, the new system is not some sort of hyper selective system that only chooses elite employees. There are still significant numbers of people arriving to do lower earning jobs.

The data above doesn’t let us come to any rounded view on the new system.

We can’t see current employment rates because we don’t know how many people from each country are in the UK. The 2021 census for England and Wales suggested that the employment rate for people age 20-64 was lower for people born outside the UK, with massive variations between people from different countries. Hopefully we will get more up to date data once ONS starts its “transformed Labour Force Survey (TLFS)” from September 20242.

It is also just much too soon to see the longer term effects of the new system. Lots of routes like the graduate route will only have their full impact in data that is yet to come. But so far it doesn’t feel like a step change.

Data disaster

From a policy point of view my argument is

Given the costs in terms of capital dilution, housing market pressures and other social costs, we should aim to make sure that migrants are strong net taxpayers, not just neutral. To that end we should aim to make migration lower by making it more selective.

When considering the economic impact of different migrants and different groups of migrants, we need to look in the round at earnings, employment and other things that influence whether people will be net taxpayers, like family structure, age and stay rates.

We can see enough to know that there are likely still significant numbers of people coming who will be net recipients not net taxpayers. But we have far too little of the data we need to make the ideal judgements about point (2). It is shockingly bad really:

Data on population by nationality has also been suspended, with the last data from 2021 (which was overtaken by the census anyway).

As well as not being able to see the stock, we cannot even see flows by nationality. ONS is in the process of rebooting its estimates of migration, and so far has only published migration flows for five non-EU countries.

The census, off which many other things are calibrated, was taken during the pandemic, at a time of huge population churn.

While the Labour Force Survey is being rebooted our only good source for employment rates by country of birth is the census (and that’s for 2021 only, and England and Wales only).

I think our migration policy could be better, and what data we have makes me think we should be more selective. But one thing I can say with absolutely confidence is that we need to massively improve the data.

In a counterfactual with lower migration relative prices between London and the rest might have been different - more people from the rest of the UK might have moved to London, diffusing the impact. Interest rates and possibly supply might have been different too, though as the graph above shows, supply doesn’t seem to respond much to population growth.

In the meantime ONS is producing data for some aggregates like EU and non-EU, but it looks screwy to me, I guess because we don’t know how many people are in the country. For example, it suggests numbers in the country from the EU have gone up over the last two years, while the ONS net migration figures suggest net emigration.

Thank you very much for this, Neil. You are doing a valuable task. What I must add, however, is that this is – ipso facto – a damning indictment to the government's policy over the last 20 years. In 2022, more people moved here than between 1980 and 2000 combined. I would love the opportunity to discuss this a little more with you in depth (by e-mail or on call perhaps?), because I think that there are ways the Conservative Party can improve on this in a meaningful way that would show in the polling numbers. A Starmer government is not an inevitability, and nobody wants to see it – but unless something changes, I and many others will be voting Reform at the next general election.

If you had to come up with a guess of the cost of benefit of the mean migrant, what would you say it is?