The relationship recession & the birth gap challenge

Key things we learnt & changed our minds on in 2024

This is a joint post with Phoebe Arslanagić-Little of Boom.

We – Neil and Phoebe – work together on the birth rate challenge at the New Deal for Parents project at Onward.

The New Deal for Parents looks at how policy can close the gap between the number of children people say they would like, and the smaller number they actually have, by making life easier for parents and families.

Now, after the New Deal for Parents’ first full year, here are seven things we learned and changed our minds on during the course of 2024. If you have ideas and comments on the below, you can reach us by emailing Phoebe at phoebe@boomcampaign.org.uk.

1. Relationship formation is key. John Burn-Murdoch had a superb piece in this weekend’s FT, looking at how the decline in the number of people having children is being driven by a decline across the developed world in the number of people forming couples:

This is one of the biggest takeaways from our first year of work. Understanding falling birth rates in Europe today means understanding the European decline in relationship formation. As social scientist Alice Evan writes, nearly 20% of men aged between 24 and 54 in the EU now live alone and single-adult households with no children saw the fastest growth rate between 2013 and 2023.

As people form relationships later in life, and some not at all, it becomes more difficult for people to ever start their families. Potential culprits include: young adults living with their parents for longer than they want because of high housing costs; and how, with women increasingly better educated than men, it becomes more difficult for women to find male partners who are as qualified and high earning as they are.

2. Helping people go from 0 to 1 child versus supporting people to expand their families are distinct policy challenges with distinct solutions. As Finnish demographer Anna Rotkirch emphasises, Nordic-style family welfare programmes based around child benefits and good parental employment rights do work to help people expand their families. The most significant challenge is to establish what works to help people who want to become mums and dads in the first place to do so. Do you have thoughts about this? Get in touch with us!

3. Birth rate decline plays out very differently from region to region. Focusing on topline figures about falling fertility rates disguises the fact that very different trends cause birth rate decline in different countries and even inside countries between different regions. Increasing childlessness is driving birth rate decline in Finland, but smaller families drive it in Germany. One-child families are becoming more common in Scotland, but two-child families remain the norm in England and Wales.

4. Avoiding Culture Wars-style polarisation is vital. Already in the US we are seeing the birth rate challenge become politically polarised. The birth rate challenge is too important – for individuals who increasingly can’t have the children they want, for our economy, for us all – to let that happen in the UK.

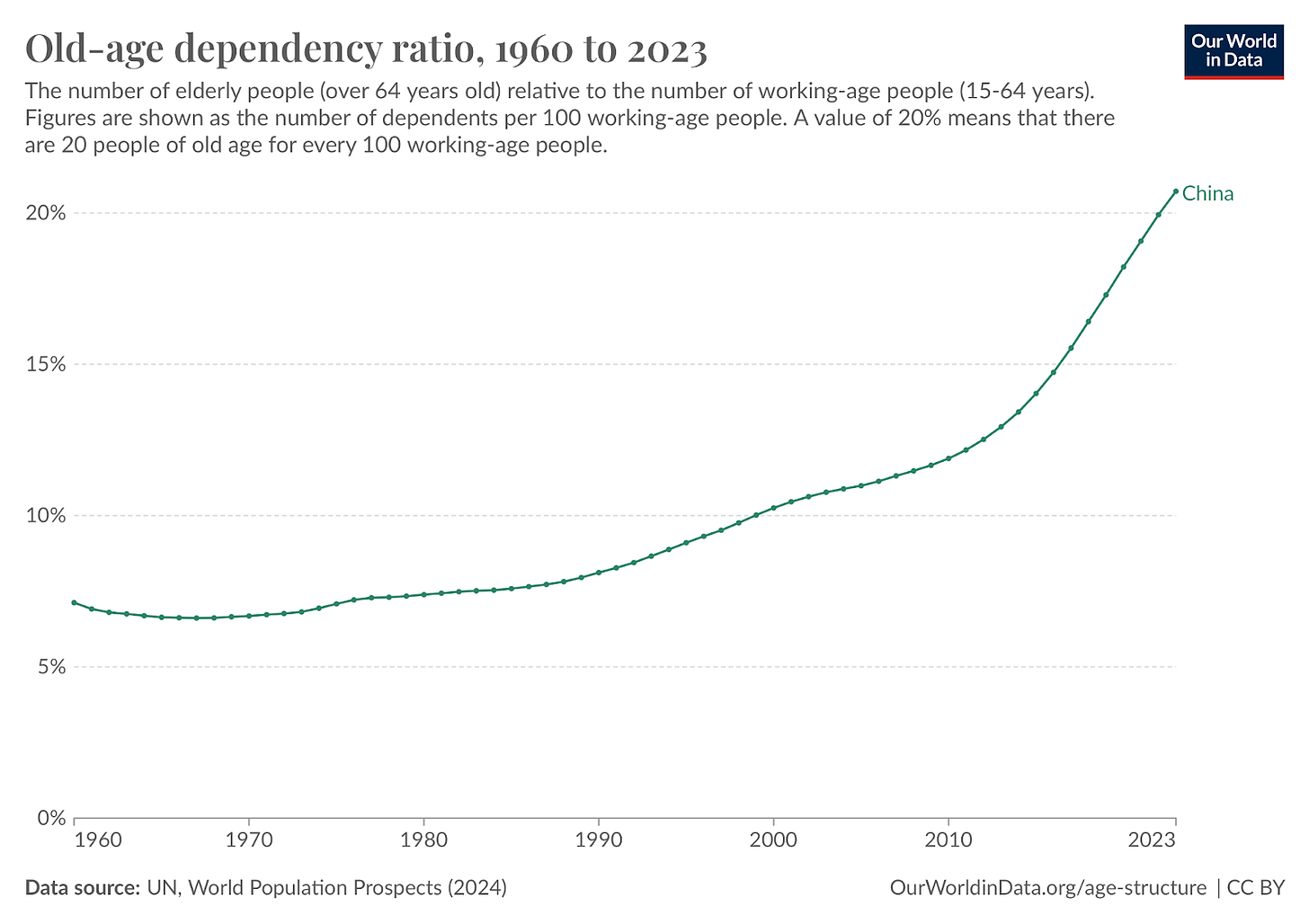

5. The global birth rate challenge doesn't just affect wealthy developed countries – many nations will get old before they get rich. Paul Morland’s book No-one Left, published in 2024, explains how a large number of countries will face dramatic demographic challenges before they get rich.

Take Thailand – in the 1950s Thailand had 70 people aged under 10 for each person over 80. But within a generation there will be more Thai people aged over 80 than those aged under 10. For fast ageing countries like China, their sheer size means immigration can't plug the hole.

6. A parent gap is opening up between rich and poor. There is mounting evidence that wealthier people are increasingly more likely than poorer people to become parents in countries like the UK and US. Access to family life is becoming a social inequality issue. Phoebe wrote about that here.

7. We saw some very interesting visualisations of the effect of age on fertility.

The first chart below looks at your chances of achieving a desired family size versus the age at which you start trying:

The second chart (from an interesting paper by Geruso et al (2023)) challenges the idea of a “cliff edge” of fertility for women - and finds instead linear decline from age 20:

The last chart below (from Yale professor Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham) shows how the shift to having kids later has pressed up against the (current) limits of biology:

Many of us do not have a clear understanding of the relationship between age and fertility. But how do we communicate this information in a way that both: reaches people; and is helpful rather than alienating?

We’d love to hear ideas on this question.

Wrap up

We learned a lot in 2024. And the discussion about these vital issues accelerated too. On Friday Lara Spirit wrote a great column on these issues in the Times, and mentioned the book of essays on this that the Social Market Foundation have out soon. There’s still lots more to learn, and plenty of debate about priorities. But at least we are now having a growing debate about these massive issues.

“…how do we communicate [info on the relationship between age and fertility] in a way that both: reaches people; and is helpful rather than alienating?”

Very rarely do I think the answer to policy challenges is to cram more into the school curriculum, but this seems a good topic for a biology or geography syllabus.

Really excellent piece with key thoughts to explore further.

One that resonated for me was the idea that having more than one child is increasingly reserved for the wealthier in society.

Anecdotally that lands for me. I am a parent of three myself and our family were in a higher earning bracket (and also chose to live in a country where childcare was inexpensive and commuting a non-issue, both of which made being an active parent easier). Beyond myself, the majority of my peers (in their 50s, with similar education and income) have three children, some four, some two, but I'd say three is the average.

I then look at children of my peer group and those who are in relationships (some aren't) aren't even considering starting a family until into their early to mid-30s. None of those adult children of that group have indicated a desire to have more than one or maybe two children.