Why we need a "New Deal for Parents"

Why we started our new campaign

Centrist French President Emmanuel Macron yesterday pledged to boost falling birth rates through policies to bring about what he called a “demographic rearmament”. “France will also be stronger by boosting its birth rate,” Mr Macron insisted. “Until recently, we were a country where this was a strength”

To this end he promised amongst other things a new form of parental leave which will be “better paid”, and “allow both parents to be with their child for six months if they so wish”.

It’s hard to imagine British politicians using Macron’s kind of language, but all over the world, ageing populations are prompting politicians of all parties to think about how they can make their countries more child-friendly.

Earlier this week I spoke at the launch of the “New Deal for Parents” in Parliament. I’ve launched it together with think tanker Phoebe Arslanagić-Little, former divorce lawyer Siobhan Baillie MP, and former housing minister Rachel Maclean. It’s based at the think tank Onward.

It has a double purpose:

To improve life for children, parents, and those who want to be a parent,

To help more of those who want to have children to do so.

Politicians are squeamish about talking about these issues for various reasons. The fact that wicked regimes in the twentieth century were pro-natalist has cast a long shadow. The history means that even the mildest ideas to help parents can prompt a kneejerk reaction. As one recent Guardian piece gloriously pointed out:

“Mussolini introduced a punitive tax on bachelors, and Meloni has halved the VAT on nappies and baby milk”

It’s not obvious to me that such mild measures to help parents with the cost of living must lead instantly to totalitarianism, but this kind of hyperbolic reaction is one reason people hold off talking about such an important subject.

The other reason politicians don’t talk about this is that the business of having children is so fraught and so personal, and finding the way through the emotional minefield requires care. Not everyone wants kids. Some want children and can’t have them, and it is a huge thing for them.

Obviously, policy on such a personal area must never be about telling or pressing people to do something they don’t want. But there are large numbers of people who would like children (or more children) but feel they are held back by different factors. On the windswept touchline of my daughter’s football club on Saturday, I was chatting to a constituent who would like another (and who is great dad) but feels he can’t afford it.

As is now quite widely known, there is a big gap across most developed countries between how many children people say they would like, and how many they actually have: in the UK the average woman would like 2.35 children, but the fertility rate is just 1.55.

Declaration of interests

We have two children via IVF. Our youngest (our son) is the result of our eighth and final try at IVF. I remember exactly how it felt every time it didn’t work, and it is one of the worst things I have ever experienced. But ultimately, we are the lucky ones.

Huge numbers of people in my age bracket have been on the rollercoaster-of-hope-and-fear that is IVF. You often don’t find out how many are having IVF until you start talking about it. My heart goes out to all of those who are trying.

My wife still slightly shudders at the sound of the timer alarm on the iPhone, which we used to use to time the pregnancy tests. And I will remember to my dying day what it felt like when it seemed like our last go at IVF hadn’t worked, and then, when we looked again a couple of minutes later, we saw the faintest of faint pink lines on the pregnancy test. The resulting toddler gave me a nice hug on my way to work this morning. We’re lucky people.

Big changes for small people

There are obviously loads of things we could do to make life better for parents and those who want to be parents. Some of the things we are going to work on first as part of the New Deal for Parents are:

Access to fertility assistance

Enabling working parents to keep more of their money

Making housing affordable for parents

Parental leave

Childcare

We are just getting this thing going, but let’s have a look at the first three of these. I’ll come back to parental leave and childcare in another post.

Fertility assistance

Access to IVF through the NHS is very variable. Very few ICBs have policies in line with NICE guidance, and in some places you may struggle to get IVF on the NHS at all, never mind multiple rounds. I recently asked a Parliamentary Question about how much was spent in total on fertility treatment and what was available where. In both cases NHSE said they didn’t collect the data centrally (why not?).

However, IVF availability was mapped in 2018 by the group “Fertility Fairness”, showing how many rounds were being funded, and there was significant variation:

This variation in access matters a lot to the lives of many would-be parents. My wife and I seriously considered moving to Northumberland in order to get better access to treatment. We were lucky that we managed to pay for ourselves most of the way, but others are not so fortunate.

There are many pressures on health spending, but one thing that would undoubtably help more people become parents would be improved access to IVF. In recent years the NHS mental health standards have demonstrated how the setting of clear service standards can massively change behaviour by local health systems.

Enabling parents to keep more of their own money

The UK’s tax-benefit system is not very child friendly compared to most of our major European peers. We recognise children in the benefit system, but (unlike lots of other countries) we no longer recognise children in the tax system.

Between 1909 and the late 1970s people got an extra tax allowance if they had children, on the solid logic that providing for their children meant they had less left over to pay tax. This is the same “ability to pay” concept that justifies higher earners paying more tax. I will come back to why it was removed in a moment.

But the upshot is that in the US and many other European countries parents pay much less tax than similar people without. But that’s not the case in the UK. (I think the tiny gap below is the marriage allowance rather than anything to do with children).

Like other countries we recognise children in the benefit system - but because we don’t in the tax system, the overall effect of the tax-benefit system is less favourable to parents than in other countries. The chart below shows the difference in the amount of tax paid minus cash benefits received for three different household types, depending on whether they have children or not:

The net effect of the tax-benefit system is that current support for children is not enough to offset the costs of having children for most households. So children are more likely to be in poorer households, after equivalising for the composition of different households. 27% of children are in the poorest fifth of households, just 13% are in the top fifth after housing costs.

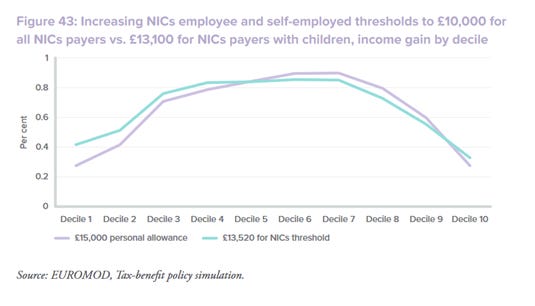

For that reason tax cuts targeted on people with children tend to have more progressive distributional effects than all-round tax cuts with the same cost, as noted in a report I did a few years back:

How we got here

The history of children in the tax-benefit system is long and complex, but here’s a super-short summary. The striking thing is how the principles of the system have varied so much over time.

•1909 The 'People's Budget’ creates a £10 income tax allowance per child, because parents have less money spare to pay tax.

•1945 The Family Allowances Act creates a universal benefit of five shillings per week. Politicians are determined to avoid a return to the means-tested benefits of the interwar years which were intrusive and created bad incentives. But the new benefit is NOT for the first child - only for families with two or more, because larger families are more likely to be poor. Ad below:

•1970 The Family Income Supplement – politicians legislate for the return of means-tested benefits for working families with children. Frank Field and other Labour child poverty campaigners go mad at Ted Heath for returning to means-testing.

•1975 Child Benefit Act legislates for Child Benefit to replace both Child Tax Allowances and Family Allowances, creating a universal benefit for all children, including the first. James Callaghan attempts to wriggle out of the manifesto commitment to do this, but is defeated by civil service leaks. From 1977 to 1981 Child Benefit payments start and roll out.

•1986 Family Credit - The Thatcher government expands means-tested, in-work benefits for parents.

•1986 Green Paper “The Reform of Personal Taxation” - Nigel Lawson proposes reforms to allow married women to keep their tax affairs private and to reduce the discrimination against one-earner married couple families. He proposes transferrable tax allowances within families as part of the new system, but these are not introduced, something Lawson strongly regretted.

•1990 to 2000 Gradual rollout of individual rather than household taxation.

•1991 John Major introduces a higher rate of Child Benefit for first child only.

•2003 Reversing Labour’s historic support for universalism, the New Labour Government introduces Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit, further increasing the size of means-tested benefits. CTC is available to out of work families, making it effectively a large, means-tested child benefit.

•2012 The Welfare Reform Act creates Universal Credit, which makes benefits more household-based even as the tax system has become more individualised. UC increases conditionality for non-working spouses and makes the system more generous to single earners. From 2013 UC has gradually rolled out, though this is still not complete, with 5.2m on UC versus 1.8m on legacy benefits as of August 2023.

•2013 The High Income Child Benefit Charge. The Coalition government withdraws Child Benefit from couples or people with individual earnings of £50-60k a year.

•2015 A two-child cap on CTC / UC is announced, starting in 2017.

So to summarise: we used to recognise children in the tax system but then stopped doing so; we insisted on universalism, then introduced more and more means testing; we focussed children’s benefits only on larger families, then only on smaller families; we individualised the tax system (even more than intended) while making the benefit system increasingly household-based.

Make of that what you will, but we politicians can’t be accused of excessive consistency over the last century.

The upshot of it all is that our tax-benefit system is less child-friendly than many other similar countries. There are also some increasingly serious issues with some of these policies. I will pick just one - the High Income Child Benefit Charge.

High Income Child Benefit Charge

This was introduced explicitly to save money. It was one of the less unpopular ways to do so: saving money is never easy, as all Chancellors discover. The below is not a criticism of Cameron or Osborne given the context of their attempts to clear up a record structural deficit. However, time has moved on, and so should policy.

Even if you think that we should means test child benefit, the design of the policy is pretty blunt. The chart below from the IFS shows how high the marginal rates are for parents.

And as the IFS point out, the effects are getting worse over time. The range over which child benefit is withdrawn is frozen (so falls in real terms), but the value of child benefit is not, so the amount of benefit withdrawn with each additional £1 of earnings increases. That’s why the hump above moves left, and why it gets taller.

By 2025–26 the worker with two children is due to see a marginal tax rate in the hump of the schedule of 65%. That’s hard to defend.

26% of families with children (2 million) are now losing some or all of their child benefit - double the proportion when the policy was introduced a decade ago.

But in reality it is worse still, as increasing numbers of parents will also be paying off student loans. This means their marginal withdrawal rates are a further 9% higher above £27,295 (for the main ‘Plan 2’ loans). Postgraduates also pay a further 6% on everything above £21,000, which makes it 15% above £27,295.

The Resolution Foundation estimates that two thirds of those in the 50-60k taper zone are graduates. Around 2.5 million paid student loans last year and the numbers are rising fast, so over time increasing numbers will be paying back student loans as well as facing the High Income Child Benefit Charge. So for graduates and postgrads the graph above looks much worse. Someone paying off an undergraduate loan with 2 children is facing a 70% tax rate, and a postgrad 76%. And this is before the effects of fiscal drag raise these rates further in the way the IFS has described. This obviously needs fixing.

Housing

Home ownership fell sharply between 2002 and 2015. But the effect was very uneven, with ownership rates actually increasing among older people, and falling even more sharply than average among younger people who might be trying to have kids.

This has meant a growing number of families with children are in the private rented sector:

And of course more young people are living with parents, as this FT graphic shows:

I have written before about how to get more houses built in the right places. That’s obviously a massive challenge that goes beyond the scope of this piece.

But it is worth noting here that a number of other countries do more than us to help working families with housing.

For example, in Germany the Baukindergeld programme offers people a grant of €1,200 per child per year for 10 years in order to buy their first home.

So that’s €12,000 (£10,286) per child over a decade. For families with two or three kids that is a huge contribution to housing affordability, and to parents’ ability to afford more space.

And that is one of the big factors delaying or limiting people from having more children. Though there is academic debate about this, recent evidence suggests high housing costs have a negative effect on the number of children people end up having. As well as supporting people with IVF, we need to help people get on with their lives, and have children earlier, at a point where it is easier.

Conclusion

Helping parents is an important goal in its own right, given the impact on children, who tend to be in households that are worse off than average. And the debate about how to better support parents is coming into focus all across the world, as leaders see the effects of an ageing society. Our new campaign hopes to shed light on all this, and build momentum to fix it.

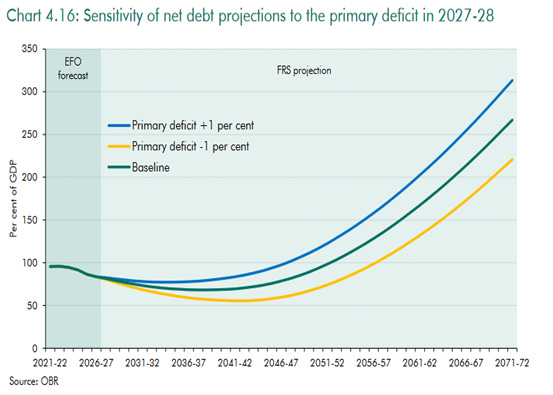

Some of these things will cost money to fix. How can we afford it? We will come up with detailed answers, but when you look at the consequences of an ageing society for the public finances (shown in the OBR chart below), I’d argue we can’t afford not to have a New Deal for Parents.

Articles for further reading:

Natalism for Progressives, Jeremy Driver

Baby Bust and Baby Boom, Social Market Foundation

Understanding the baby boom, Anvar Sarygulov & Phoebe Arslanagic-Wakefield

Closing the birthgap, NCSU

A 12 step programme, More Births

We can buy new culture, Robin Hanson

Pro-Natal Policies Work, But They Come With a Hefty Price Tag, Lyman Stone

I was moved by this article. Thanks for sharing. As a Dad of two, I find the financial pressures increasingly difficult. I feel at times as if policy is actively working against parents. I realise it's a choice to have children but a falling birth rate is not a good outcome for anyone.

Why can’t parents pay for childcare from pre-tax income? Why does the Government increase the no of childcare hours without appreciating that nurseries are struggling to break even on the existing entitlement. Nurseries will struggle even more to meet new entitlement, resulting in fewer places available which puts even more pressure on access to existing childcare provision or forces one parent to take a career break, neither of which are financially palatable and act as a break on having a/nother child.