The impact of the National Insurance increase on public services

A lack of answers from government means massive uncertainty for public services

Background

This post is mainly about the impact of the National Insurance increase on public services. But it is worth recapping how the increase works.

Before the General Election Labour promised not to increase National Insurance - or any “taxes on working people”. Since the election they have increased National Insurance, a tax which - uniquely - is only paid by working people.

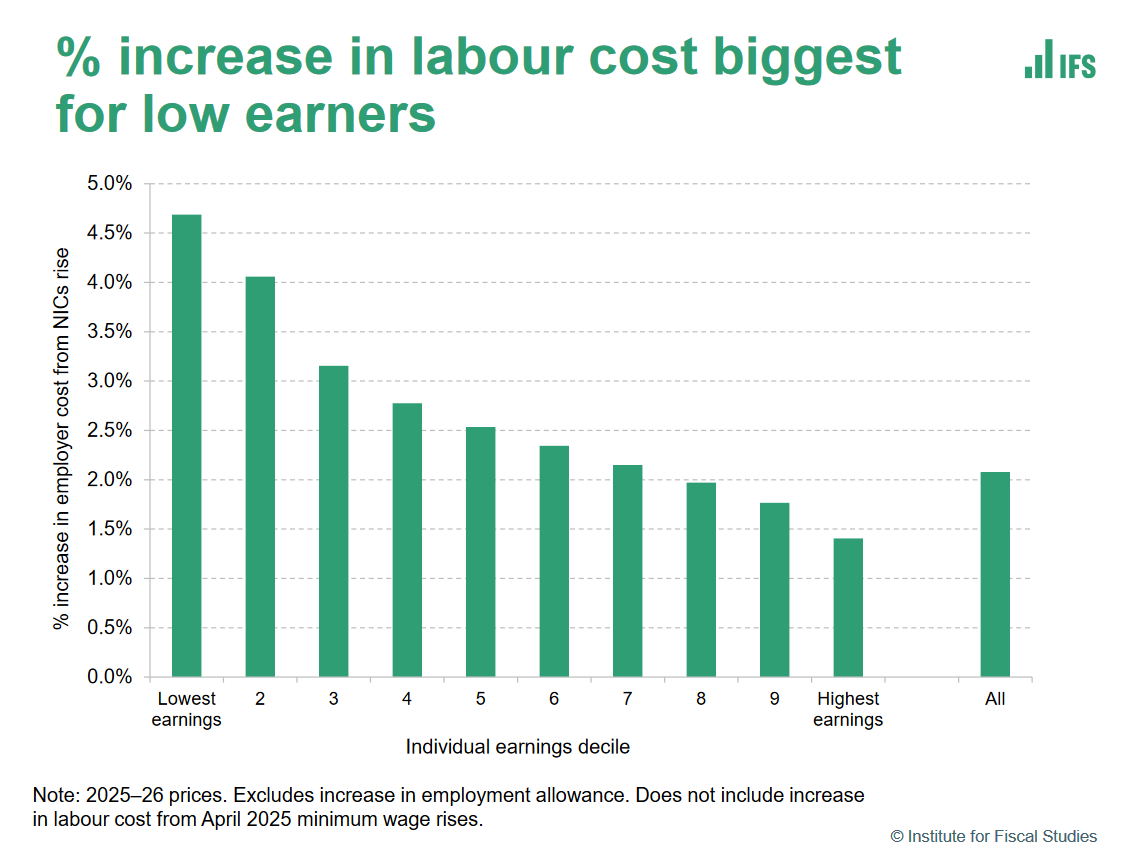

More surprisingly still, they have also chosen to focus this tax increase on lower income workers, by aggressively cutting the earnings threshold for Employers NI from £9,100 to £5,000, as well as increasing the rate.

This reduction in the threshold means the impact is sharply focussed on those who earn less - particularly part time workers:

This impact on lower-earning workers in turn has meant the impact is larger on women than men, as the IFS have pointed out.

Struggling to spin this, Labour eventually hit on the unfortunate line that the rise in Employers NI meant “working people will not see higher taxes in the wage slips that they receive”.

They are treating people like mugs, hoping that people don’t understand tax incidence. Unfortunately, wages are exactly where working people will see the impact. The OBR and IFS both point out that it will hit wages. The OBR EFO noted that:

“from 2026-27 onwards, we assume […] that 76 per cent of the total cost is passed through lower real wages, leaving 24 per cent of the cost to affect profits.”

Even the Chancellor has been forced to admit that, as she euphemistically puts it, “wage increases might be slightly less than they otherwise would have been.”

In the case of many public services there is no profit, so adjustment has to come through wages (which the government often sets) or the real resource level for the service.

The public services - who is compensated, and on what basis?

The Treasury has talked about compensating the public sector for the cost of the NI increase. But all HMT really means by is that they will take it into account (in some way) when setting spending envelopes. There’s no automatic protection or exemption for the public sector.

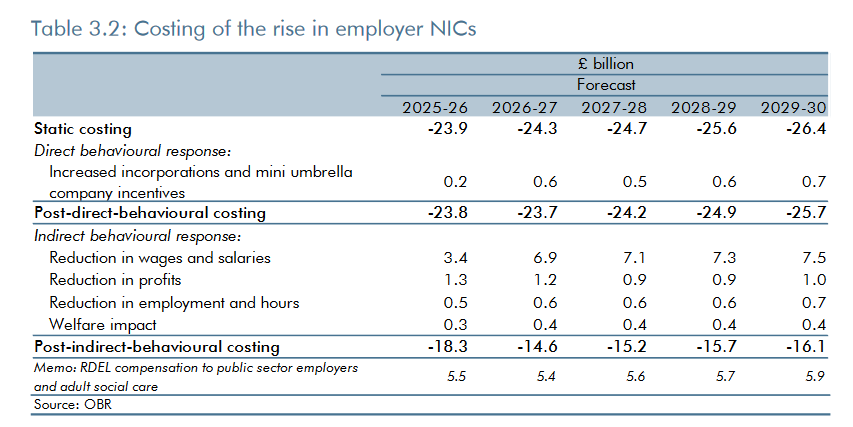

The impact of the NI hike is big. Page 118 of Budget includes a table suggesting an impact on the public sector is around £5.1 billion a year by the end of the forecast:

I noticed that the OBR’s Economic and Financial Outlook (page 55) had a somewhat different figure, of £5.9 billion for the same year (2029/30). I noticed the OBR also talked about “public sector employers and adult social care”.

Last week I asked the OBR about the difference. Yesterday, they emailed back to say:

They also published the correction below, which strips out the reference to adult social care and reduces the total by £800m in the final year. As Ben Zaranko from the IFS pointed out, this: “perhaps suggests that the Treasury was intending to compensate adult social care providers for the costs associated with the employer NICs rise, before changing its mind...”

A wider issue

Social care providers are up in arms about the impact of the NI increase: they have a lot of those female/part time/lower paid workers who are most affected.

But social care is just one example of a wider issue. Most employees in social care are do not work for public sector employers, but for private providers that are often government-funded but not government-owned1.

The impact on services that are excluded from compensation has become one of the simmering issues after the budget: be it the exclusion of GPs or social care or nurseries or universities.

But there are other problems too about the idea of “compensating” public services for the NI increase beyond certain services being excluded:

Indirect impacts. As departments negotiate with the Treasury they are likely to find that HMT takes a different and more restrictive interpretation of how large the impact is. As well as excluding public services that are not public sector, Ministers are refusing to say whether they will take into account the indirect impact on public sector organisations. For example, schools have suppliers and indirectly employed staff - the costs of these will go up. Or local authorities hire private firms to provide transport to schools: their costs will go up, and so on.

Winners and losers. Two different public sector organisations (two schools, or hospitals or local authorities) may have quite a different staffing mix, with more part time or lower paid workers, or more outsourcing. HMT may or may not take into account the NI bill when it sets future funding levels. But if it does so it will probably do so through normal funding formulas, rather than directly compensating organisations for their specific costs - and this will lead to relative winners and losers.

Uncertainty for public services

Ministers are refusing to answer questions on how big the NI hit will be to different public services. The last thing they will want to do is give public service providers the leverage of being able to say they need “at least £X to stand still”. For the same reason departments in turn won’t want to provide figures.

I’ve asked a Parliamentary Question about how much of the £5.1 billion the treasury refers to is going to each department, and we will see if we get an answer. But I’m not optimistic. Asked to provide this in the Commons the other day, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones declined.

Refusing to say how much it thinks it will need to compensate departments or services for the NI hike makes it harder to understand the real impact of funding decisions. This is how the Treasury likes it, but makes it but creates massive uncertainty for public services trying to plan ahead.

Who’s in and who’s out?

The question of which bits of the public services are to be compenmsated and which are not affects multiple departments.

Health

In DHSC quite a lot of services are not in the public sector, including NHS GPs, NHS Dentists, NHS Community Pharmacy, not to mention optometry, most of the care sector and the hospice sector too.

Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones said, “GP surgeries are privately owned partnerships and not part of the public sector and will therefore have to pay”, sparking fury from family doctors.

Right after the budget GP leader Katie Bramall-Stainer said that she had spoken to ministers and tweeted: “Streeting Smyth & Kinnock now locked in discussions with Treasury.”

GPs’ are naturally concerned they will end up losing out: a spokesman for the BMA told the Telegraph that it would be “disingenuous” to attempt to position any reimbursement as part of a future funding deal, given that it would only return what was being taken. The BMA wrote again to Wes Streeting about it yesterday.

The combined cost of the NI hike and increased National Living Wage can be large for practices, with one GP giving this example:

On TV Wes Streeting said that all for non-public sector public services (including charities) the cost would simply form part of future funding talks: “We’ll be negotiating the GP contract with them as well as taking other steps like setting the hospice grant… the dentistry contract, and obviously on social care I want to make sure that we’ve got the care provision in place"… I’ll be taking into account the added pressure of Employers National Insurance Contributions.”

While Streeting has reassured Labour MPs that he will come up with greater funding for hospices (which get very little government funding at present), the same pledge hasn’t been made for social care. The Local Government Association says that the combination of the NI increase and minimum wage increase “will almost certainly absorb all of the grant increase for many councils.”

Education

Ministers are so far refusing to give any details about compensation.

Childcare is one of the most acutely affected sectors, as it has a large number of lower paid and part time workers, and it is a people-intensive business. It is exactly the sort of business that it really hit by the decision to raise tax by cutting the threshold. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has pointed out that nurseries are particularly affected by both the NI increase and the increase in the National Living Wage. For a typical full-time childcare worker earning £25,000, the employer NICs bill will jump from around £2,200 to nearly £3,000—a rise of over a third.

Unsurprisingly the sector is warning that unless government uplifts funding rates to compensate there will be a lot of nurseries closing.

Most providers are not in the public sector: in 2023 there were 1,043,600 places in private and voluntary groups, and 164,900 in childminders, compared to 349,600 places in schools. But the government is funding 80% of childcare hours, according to the National Day Nurseries Association, making government funding rates crucial.

In the Commons Laura Trott asked Bridget Phillipson about how big the hit to nurseries and early years providers is, and whether they would be compensated. Phillipson declined to say how much it would cost, and would say only that “We will set out more detail on funding rates in due course.” Pushed, she said she would say more “soon”.

In the same session I asked about what the cost was to schools and colleges - and whether any compensation will include the costs they will face from higher prices charged by suppliers and indirectly employed members of staff - such as caterers, IT and premises staff.

Phillipson would not say what the cost to schools and colleges was, or whether the indirect costs will be included. She would only say that “Schools and colleges will be compensated at a national level.” The reference to the “national level” sounds like any compensation may not be equal to the bill any individual school faces. According to the Budget core schools resource spending is supposed to increase by £2.3 billion next year in cash terms - but we don’t even know if the NI costs facing schools are supposed to be met from that, or from further HMT funding.

Universities are another big public service not in the public sector. The Higher Education Sector has produced its own estimate of the cost of the NI hike, saying that it “will add around £372m to the sector’s pay bill”. This almost exactly wipes out the benefits to the sector of the decision to increase tuition fees, which the IFS estimates at £390m.

Effectively one broken promise (on fees) is paying for another broken promise (on tax).

Universities are an interesting example. Because of the timing of the fee increase, Ministers can’t pretend that they will be “compensated later in negotiations” - at least not in the near term. And I think this is a precedent other sectors will be alarmed by: ministers hail a “funding increase,” but the sector discovers it is actually just eaten up by the NI increase.

Defence

Defence is one department I can see that has answered a question on the cost of the NI increase.

My colleague Caroline Johnson asked what the (a) direct and (b) indirect costs were. In answer Maria Eagle said that:

“The changes to employer national insurance contributions from April are expected to increase Departmental costs c.£216million in financial year 2025-26. The Chancellor has agreed to provide funding to the public sector to support with the cost of employer national insurance contributions, which will be confirmed at a future date.”

£216m would be about 4.5% of the Treasury total for that year (£4,745m).

It is unclear what this includes or excludes. In 2022/23 people covered by the armed forces pay review bodies2 had a paybill of around £12 billion, and the total central and local public sector paybill was about £245bn, which would have made defence about 4.8%.

The question this raises is why other departments are not able to answer the same questions.

The Department of Health were asked the exact same question as MOD, but in contrast they are only saying they will set out details “in due course”.

Local Government

Local Government is one part of the public sector where we do have a breakout of their share of the public sector paybill. The Treasury’s publication “Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses” says that this year (2024/25) central government will spend £198 billion on pay, and local government will spend £75 billion. On that basis you might expect a bit over a quarter of the Treasury’s £5.1 billion cost to the public sector to hit local government - so about £1.4 billion in the final year of the forecast.3

But this is just the public sector: much of local government funding flows through to services where people don’t work in the public sector: from school transport to social care to road maintance and bus funding.

Autumn Budget 2024 announced £1.3 billion in additional grant funding for local government services in the next financial year, including £600m for social care. Melanie Williams, president of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (Adass) has said that “In reality, the new money announced may end up being used to cover employers’ national insurance increases and wage increases among providers.”

Other departments

Anywhere there are public services provided by non-public sector bodies there is a risk that the Treasury will take the same attitude that it has with GPs: that they should suck it up. Some other examples might include:

Transport: where bus operators and many train operating companies are not in the public sector, along with some trams and many ports and airports.

Housing: where Housing Associations are not in the public sector (aka Private Registered Providers / Registered Social Landlords).

Culture: where a large proportion of public funding goes to non-public sector bodies.

The Charity Sector

And of course organisations providing “public services” are not the only ones performing a public service. The NCVO and ACEVO organised a joint letter of 7,361 charities and voluntary organisations, arguing for an exemption. They say it will cost the sector around £1.4 billion a year. Homelessness charities alone say it will cost them £60m.

All the main bodies representing charities have raised concerns about the impact it will have on them. Many charities have pretty fragile finances, and various charities have said it threatens their existence.

Conclusions

Particularly where there are a lot of part time or lower wage staff, the hit from the NI increase could drive quite a big wedge between the headline totals for funding announced by government and the real resource available.

The present situation where government is (generally) not answering questions on the impact on different services or their plans to address this is making it very difficult for public services to plan ahead.

This is setting up a series of negotiations with each service in which it will be left to public service providers to try and work out what impact it will have on them, while departments and the Treasury try to avoid releasing any figures.

The way the NI increase has eaten up funds from the tuition fee increase shows they effects can be quite significant and will rightly make other services feel nervous about Ministers’ current vague reassurances that they will be ‘compensated’ somewhere down the line.

According to the annual report of Skills for Care, in 2023/24 there were 1,705,000 people working in care, of whom 117,400 worked for Local Authorities, 117,000 worked for the NHS but 1,345,000 worked for independent providers.

Around 45% of public sector staff are covered by the pay review bodies.

These figures are in tables 6_5 and 7_8.

Perhaps if your government hadn’t salted the fiscal battlefield with employee NI cuts, and unrealistic public expenditure plans, we wouldn’t be in this mess? Neither major party was honest with the electorate, and if they were, the tabloids would have had a field day.

In policing, we will have the bizarre situation where they will allocate NI compensation using the funding formula rather than the actual cost. Of the £5.7m that the NI changes will cost Kent, it’s likely my allocation will be £1m short, whereas other Forces could be over compensated and receive more money than they need.