Schools policy: going in the wrong direction

Schools are better than when I was a kid. This is due to both the hard work of teachers - and also because of structural reforms that have seen better ways of doing things spreading through our schools.

Schools reform is an example of an all-too-rare thing in our politics: an area where there has been a degree of cross-party agreement, where one government has built on the work of the last.

Well, in England at least - Scotland and Wales went a different way.

In 1986 Kenneth Baker launched the City Technology Colleges (CTCs) programme. That became the Academies programme under New Labour and Andrew Adonis. Then it became bigger still under the Coalition government, with Michael Gove introducing Free Schools, allowing good schools to convert to academies, and also allowing schools to join up into trusts: families of schools working together.

I’m not arguing everything is perfect or great - it obviously isn’t. But we have made real progress. Understanding how we build on that, rather than undermine it, is key to making further progress.

What is the evidence that we made progress?

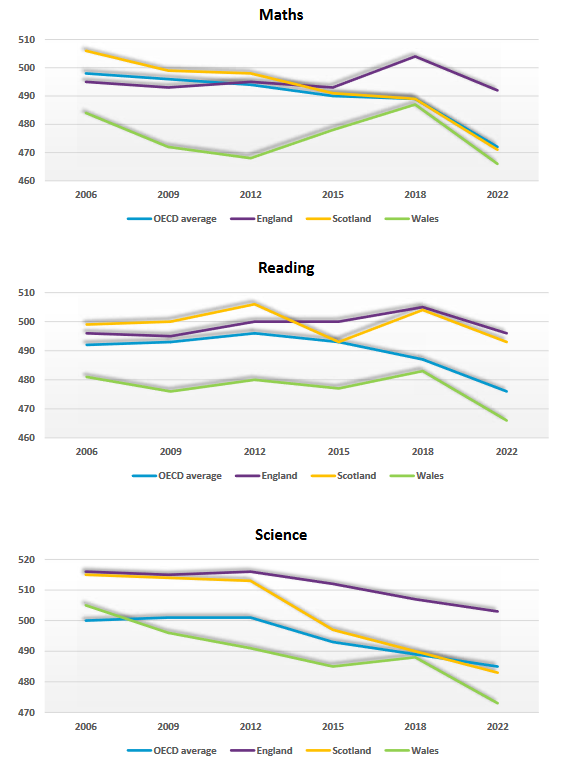

International comparisons of achievement suggest that the relative performance of pupils in England has improved. It improved both compared to other countries, and also relative to Scotland and Wales - where devolved governments pursued quite a different agenda.

Here’s how England fared on the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which compares 15 year olds’ academic performance (the charts below are from EDSK).

In all three domains England saw relative improvement compared to the OECD average since 2012. Although scores around the world fell after the pandemic, England fell far less. And in all three domains England pulled relatively ahead of Scotland and / or Wales.

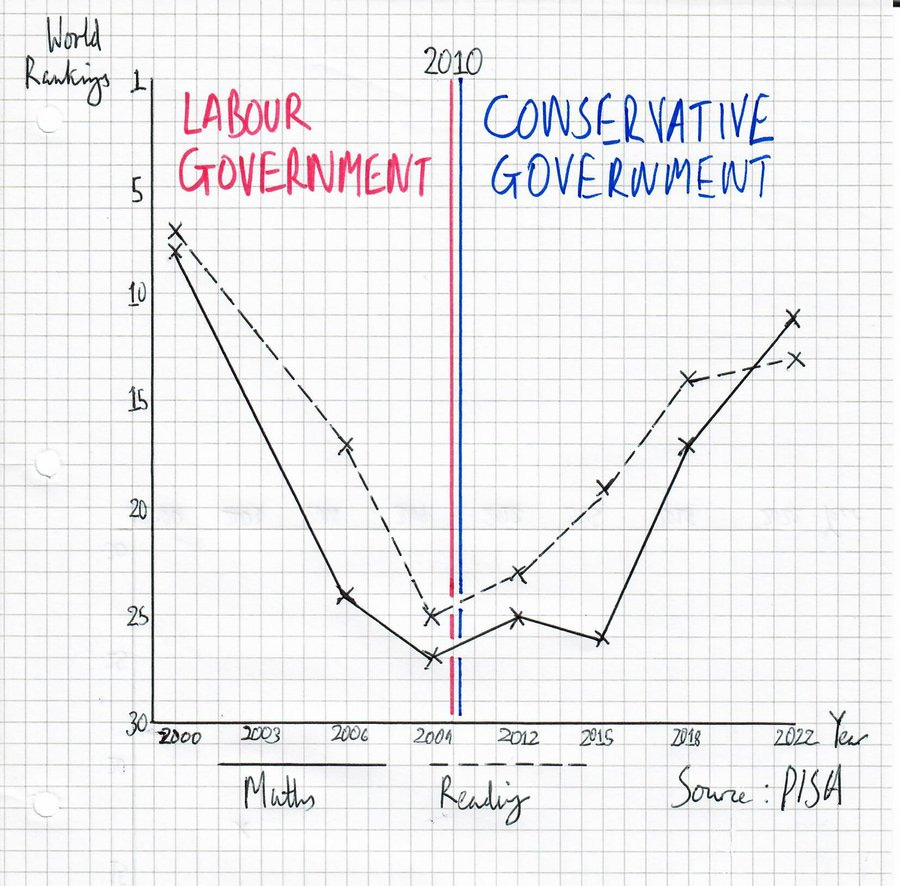

Viewed as a ranking instead of a point score, there has been a clear relative improvement relative to other countries. Damian Hinds tweeted the following lo-fi graph the other day:

What is the new government doing?

The new government has not attacked this consensus head-on. But it has moved quickly to do a lot of things which will take us in the wrong direction.

A) Ending the academy & trusts revolution

Under both Gove and Adonis, England made progress towards the goal of a “self-improving” schools system. The idea was that progress was more likely to be driven forward by teachers and school leaders - not endless micromanagement from the DFE in Sanctuary Buildings. The deal was “autonomy for accountability”. Politicians would stop micromanaging, and in return we would publish good data on pupil progress, parents would getter a better choice of good school places, and schools that persistently failed pupils would be put under new management.

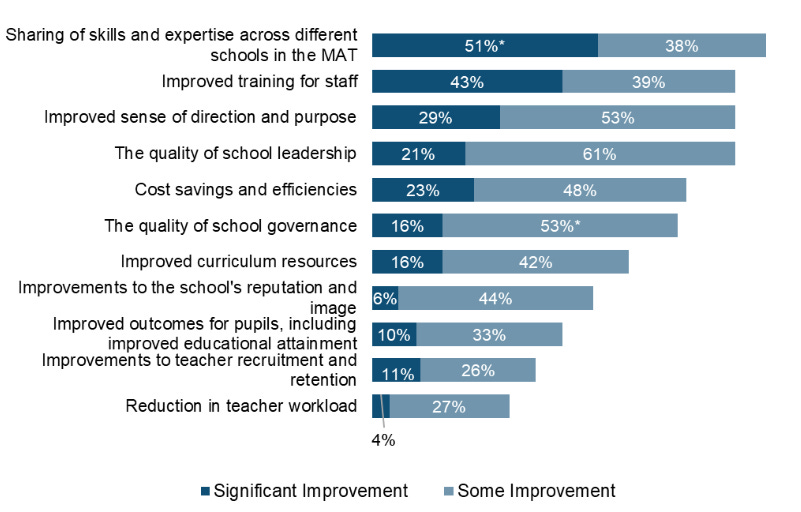

Probably the most interesting & useful thing that has happened in recent years is the growth of school trusts (Multi-Academy Trusts). In every generation there have always been miracle-working head teachers and schools that stand out. But these flashes of brilliance have faded away, rather than being scaled up.

What’s different now is that a number of school trusts are managing to replicate success at scale. They have an approach that works for more than one school.

Once upon a time a headteacher had no real peers: now as part of a family of schools, good ideas and best practices can flow between schools, and resources and back office can be shared. Schools are cooperating with each other, in ways they generally didn’t with Local Authorities. 82% of primary schools reported improvements in staff training since joining a trust, 89%, improved sharing of skills and expertise.

But Bridget Phillipson has immediately got rid of the two grants that help academisation and the growth of the best trusts: The Academy Conversion Grant is being abolished at the end of this year - and the same is true of the Trust Capacity Fund, which helped trusts take on more schools. In fact trusts that bid earlier this year have been told they won’t get anything.

The Confederation of School Trusts said the fund “has been very successful in enabling trusts to support maintained schools that need help, especially in areas with a history of poor education outcomes” and that “that will become much more difficult to do now. Trust leaders will be especially angry that ministers have scrapped this summer’s funding round.”

Last month Phillipson also “paused” the final wave of 44 new free schools. She also made comments suggesting that “paused” may mean “cancelled” in many cases, and there won’t be any more schools coming through this route. The paused schools include three sixth forms proposed as a partnership between Eton College and the Star Academies Trust, in Dudley, Middlesbrough and Oldham.

This decision is despite the fact that secondary pupils in Free Schools consistently make more progress than any other type of state school. In 2022/23 the average Free School Progress 8 score was 0.21, higher than either LA-maintained mainstream schools (0.01) or converter academies (0.10) - even though the latter were typically already good schools which converted to academy status. On average over the last five years 69% of pupils in Free Schools achieved grades 4 or above in English and mathematics GCSEs, compared to 65% of LA-maintained schools.

As well as defunding the growth of academies and ending the Free Schools programme, Labour have changed the accountability regime used to turn round struggling schools. On 2 September the government announced that single-word Ofsted grades would end with immediate effect, to be replaced in future by a more complicated “report card”.1 This also meant immediate change to what happens with failing and struggling schools.

Maintained schools judged inadequate have received a mandatory academy order since the passage of the Education and Adoption Act 2016. Prior to this, the Secretary of State for Education had a discretionary power to issue an academy order to these schools.

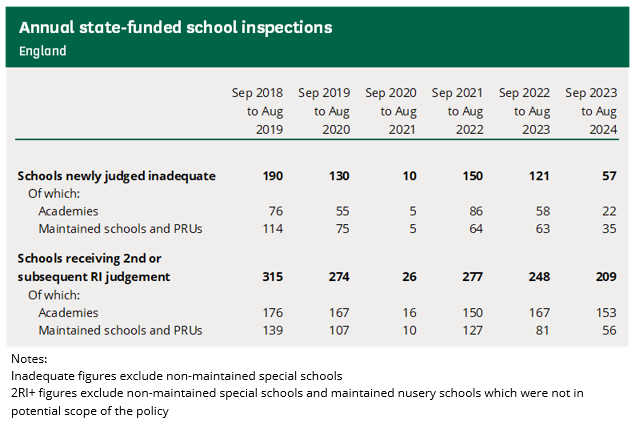

Previously a school which Ofsted rated as “Requires Improvement” twice in a row2 was in scope for a change of management, known in the jargon as “rebrokering”. This “2 RI” policy brought a significant number of schools in scope to have new management - 200-300 a year in most years, as the table from the Commons Library shows:

Instead of an option of a change of management, these struggling schools will now be referred to new “Regional Improvement Teams”. DFE are starting to recruit people to these teams, but details on how it will work are still hazy. Civil Servants in the unit-to-be-created will have to RAG-rate a huge number of schools, and work out what support package they will get, and also find people to deliver it.

As well as reducing the flow of new academies and Free Schools, Labour are also chipping away at academy freedoms for existing schools.

Many trust leaders felt that the commitment to let them get on and teach without micromanagement had already been a bit eroded. But this is happening much faster under Labour, who have changed the rules to require all academies to follow the National Curriculum. Most schools largely did - but some trusts used a degree of flexibility to do something different, be it an academic focus, or to create some kind of specialism like music and arts.

Take Michaela School. It’s had the highest Progress score of any school in the country in the last two years running. They have developed their own knowledge-intensive curriculum. They are taking highly deprived kids from a multiethnic background and getting them extraordinary results. So who knows best how to succeed for these pupils: an amazing team of teachers in a successful school, or a bunch of politicians in SW1?

Labour have also changed the rules to say that academies cannot employ non-QTS teachers. Again, the number of non-QTS teachers is not massive: there are about 13,600. The Treasury estimated that moving them all onto QTS would cost schools about £54-£127 million for the existing stock, and then £26-43m a year for the flow of new teachers. But where is the evidence that DFE know better who to employ than school leaders themselves? The original logic of this was to allow experienced teachers into the state system - from the independent sector or overseas - if the head believed they would do a good job. The thing that is really concerning is the return of the view that the Department knows better than school leaders.

Ironically this is happening as other countries are copying elements of Britain’s reforms, or doing similar things. For example: New Zealand are just about to start introducing their version of free schools (“Charter Schools”) with freedom over curriculum, staffing etc, and a more knowledge-rich national curriculum. Sound familiar?

Indeed, these ideas are working in many countries: I will never forget a visit to the Bronx a few years back to a Charter School there. When a primary school has a gun arch at the entrance you know you’re in a tough neighbourhood, but they were doing incredible things for kids in one of the most deprived bits of New York.

But in Britain, in every dimension that matters, school reform seems to be going in the wrong direction. Maybe most important of all are the dogs that are not barking: the things that are NOT being done on this front.

Instead of slamming on the brakes, we should be accelerating: from encouraging the growth and deepening of the best trusts (a sort of industrial policy for schools), to figuring out how to complete an academisation process which has currently left some LAs with a small number of LA-maintained schools. But the government’s attention seems to be on other things…

B) The Curriculum Review - moving the focus off academic standards?

The government has set up the Curriculum and Assessment Review. The terms of reference of the review are long and very broadly defined. But one main motive seems to be Bridget Phillipson’s belief that there is excessive focus on core academic subjects, and instead there should be “a broader curriculum”.

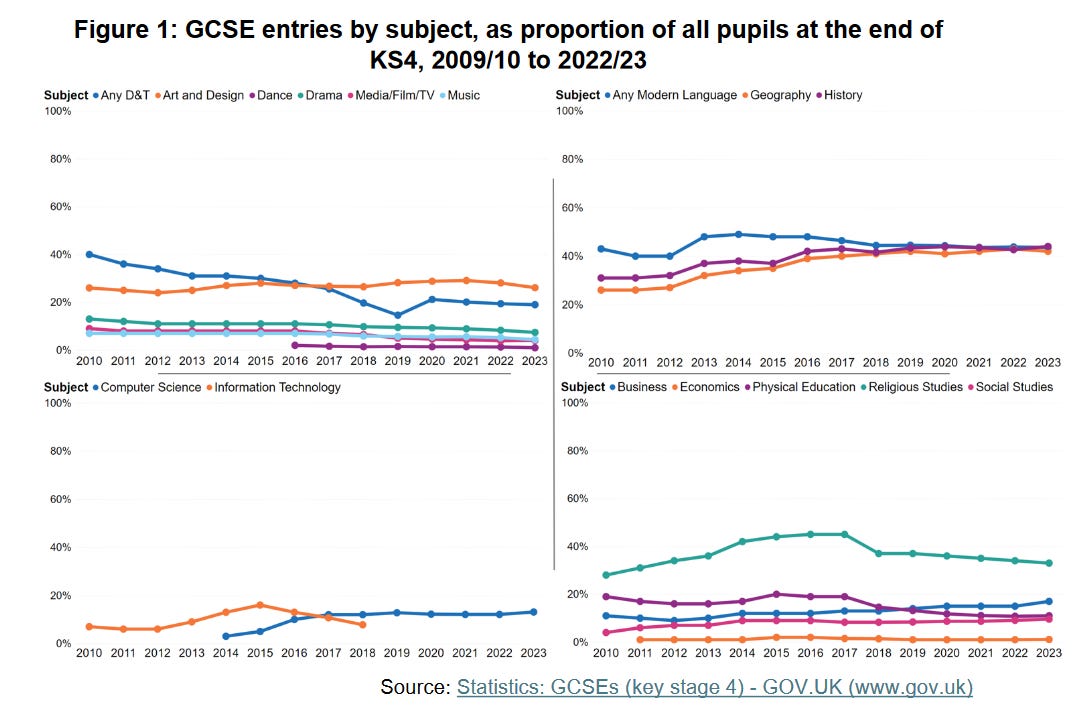

It is not clear what is meant by this. The evidence pack published alongside the review actually points out how little change there has been in the subjects pupils do GCSEs in. Design and Technology has waned, while Geography and History have increased. Other than that, not much has changed.

And even though there have been small changes in numbers doing GCSE Music, Drama and PE, even in those subjects there has been some offsetting growth in the numbers doing other qualifications in these subjects - particularly in PE.

Meanwhile there have been some very positive trends on the academic side. The share of pupils taking double or triple science GCSEs (rather than applied or single) strongly influences how many can go on to study science. Having fallen from 83% to 70% between 2006 and 2011, the share taking double or triple science is now up to 98%. The share doing triple science rocketed from just 6% of pupils in 2006, compared to 27% in 2019.

One thought floating around at the moment is that the contents of core GCSE subjects like maths should be cut back to free up more time for arts subjects.

To say the least, this is not a change the DFE should be imposing on the system. I might feel differently if an individual school wanted to spend less time on the academic core to do more of other things, and if parents wanted to choose that.

But imposing this from the centre?

The truth is that maths and core academic subjects open up more doors later on for young people - and the growth in the numbers doing A level maths in recent years is a hugely positive trend.

Phillipson says that “A star [grades] alone do not set young people up for a healthy and happy life. And where previous governments have had tunnel vision, we will widen our ambition.”

But it isn’t tunnel vision to want more young people to achieve at a high level in core academic subjects. When ministers take their foot off the gas on standards it won’t be upper middle class students who suffer.

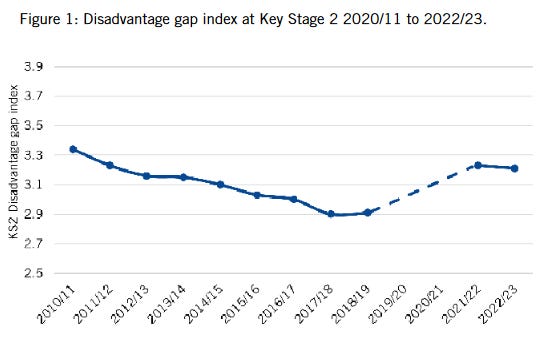

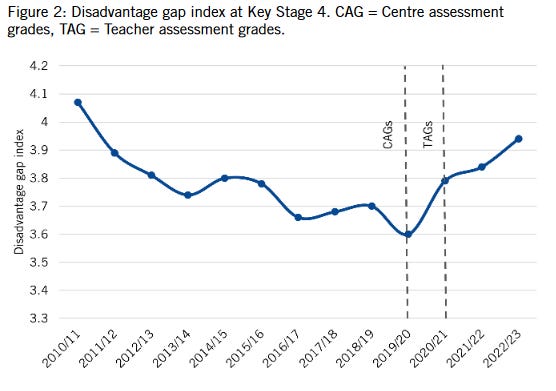

Before the pandemic the focus on standards was clearly closing the attainment gap in both primary and secondary schools, as the charts below from the Sutton Trust show. But the Covid pandemic blasted things backwards, so the focus needs to return.

The review also pledges to change the curriculum so it “reflects the issues and diversities of our society.”

Well-meaning groups of people always say they want to “put X on the National Curriculum.” In 2018 alone the roup Parents and Teachers for Excellence logged 213 news stories with various campaigns making suggestions about what should be taught in schools.

From intellectual property and bushcraft to trampolining and “feminist views of Jesus”, many well-meaning groups would like to see their particular area of focus given more time in schools. But sadly, there are only so many hours in the day, and teachers have enough on their plate teaching the basics, without being asked to also deliver whatever is fashionable this week.

The reality is that schools already spend a lot of time on the “issues and diversities” of our society. Many of the things people want to be covered… already are.

The interim report is due out in early 2025, and the final report next autumn. We will have to see what it says. The external advisors involved in the review are serious people, but Ministers’ focus doesn’t seem to be on standards: either how we ensure all children get a decent education or how we stretch the most able. Everyone is in favour of “wellbeing and belonging”, but there is a risk that if DFE doesn’t maintain focus on its core business things will slide, as they have in Scotland and Wales. There is a lot to do on behaviour, attendance, SEND and standards - that’s what I would focus on first.

Conclusion

I should declare an interest. I first had an average comprehensive education, which taught me that the average in this country is not good enough, and was marred by preventable disorder that made life miserable for teachers. I was OK, but school squandered the potential of a lot of the people around me, and stunted their chances.

I then went to an amazing state sixth form which showed me how good state education can be, and changed the lives of many young people in Huddersfield for the better. Later in life I was a school governor, and saw the torrent of paper that is fired out from DFE at school leaders and teachers who just want to get on with their job. We now have two children in a state primary school. I want their school years to be better than mine.

In many policy areas it is unclear what even works. But when it comes to schools we can see what worked. We actually made progress under multiple parties. We should be doubling down on it - not slamming on the brakes.

According to a recent report in the Financial Times: “Sir Martyn Oliver, the chief inspector of Ofsted, has proposed giving schools a colour-coded rating on each of the 10 areas, ranging from “exemplary”, in purple, to “causing concern”, in red.” Responses to this from schools were quite negative - so it may be revised.

Or rated Inadequate, then Requires Improvement.

No comment on SchoolFeeVAT Neil? You know the harms this will have on all children and the education ecosystem especially SEN.