"More representative..."

The British Transport Police recently abolished a fitness test for officers because of fears it would discriminate against women.

The Metropolitan Police recently shut down their gangs database (GVM) because of concerns that black people were disproportionately represented on it.

A leaked document titled “The British Army’s Race Action Plan”, notes that the Army plans to relax security clearance requirements for “uncontrolled access to secret assets” because it believes this is one reason it “struggles to attract talent from ethnic minority backgrounds into the officer corps”.

Across the public sector, organisations are doing things that seem surprising - and in some cases undesirable - in an attempt to become “more representative”.

The same is true to a slightly lesser extent in most large corporations across the English-speaking world. In some sectors and places it is more intense. For example, the arts and charity worlds are particularly seized of the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion agenda, of which this is part.

While many people will start with some sympathy for the idea of being more inclusive or representative, on more and more occasions this drive to make organisations “more representative” seems to tip over into things that would have been considered discriminatory and unthinkable not that many years ago.

For example: white men seeking to join the Royal Air Force were described as "useless white male pilots" by recruiters, and the RAF eventually admitted discriminating against white men after being sued.

Documents turned up during the case revealed how the RAF had blocked their recruitment in order to hit diversity goals:

“If we don’t have enough BAME and female to board then we need to make the decision to pause boarding and seek more BAME and female from the RAF. I don’t really need to see loads of useless white male pilots, let’s get as focused as possible, I am more than happy to reduce boarding if needed to have a balanced BAME/female/male board.”

Though the RAF apologised, no one resigned or was sacked over this.

Scope of this piece

It is a commonplace in politics for someone to say that some group needs to be more “representative” of Britain.

But what does this even mean?

What are the actual arguments for making the police or the army or Parliament or whatever “look more like” Britain? Too often these policies are just assumed to be necessary.

This piece looks at the arguments for and against these policies in principle, and the different types of policies that are deployed in different places.

As a spoiler, my view is that too many organisations do not think clearly about whether there is evidence that their current workforce or beneficiaries are in fact a problem, or what exactly is the problem is.

I am not an absolutist on this issue. I think that whether policies are reasonable turns on:

a) Whether there’s evidence of a real problem, and clarity about what exactly it is,

and

b) What sort of measures are used to address it.

Policies to make things “more representative” are being applied in recruitment to jobs - and some of the most drastic examples are in job-precursors like internships, scholarships and work experience positions.

But it isn’t just jobs: many organisations also apply the same logic to their customers, participants, users and beneficiaries. Theatres hold “black out” events at which only “people who identify as black or brown” are welcome. Things that are seem by some as “too white” include poetry, England’s Women’s Football team; the Museum of Rural Life. The list goes on and on.1

As well as employment in an organisation, further goals are also set for achievement (particularly promotion) and or treatment within organisations. For example, the British Medical Association has a goal to eliminate “areas of inequality affecting doctors” which include:

The disproportionate pattern of fitness to practise complaints we receive from employers, in relation to a doctor’s ethnicity and place of qualification. We want to eliminate this by 2026. The number and rate of these referrals remains low. But ethnic minority doctors are twice as likely to be referred to us by their employer than white doctors.

You might think the BMA’s goal should be to reduce the problems with fitness to practice across the board, by eliminating the problems that cause this, rather than framing the issue as one caused by employers reporting problems. It seems strange to shoot the messenger.

Representative of what?

The types of groups that can be the object of policies to increase their representation have expanded over time.

women

ethnic minorities

disabled people

transgender people

religious groups

And there have been changes of emphasis over time. At the moment there is a particular focus at the moment on increasing the representation of people with mental health conditions. For example, my local police are advertising to recruit more autistic and neurodivergent people. It might seem surprising to have a goal to bring them into a dangerous, high pressure, unpredictable business that is all about interacting with people. It would be interesting to hear them explain why they are doing this.

This list above is not quite the same as the list of “protected characteristics” in the Equality Act 2010 - the Act lists age and pregnancy as characteristics, but it is much rarer for organisations to set quotas or attempt to drive up numbers from these groups.

In response to criticisms of these policies (explored below) other characteristics are sometimes added: working class representation; representation of people from outside London and so on.

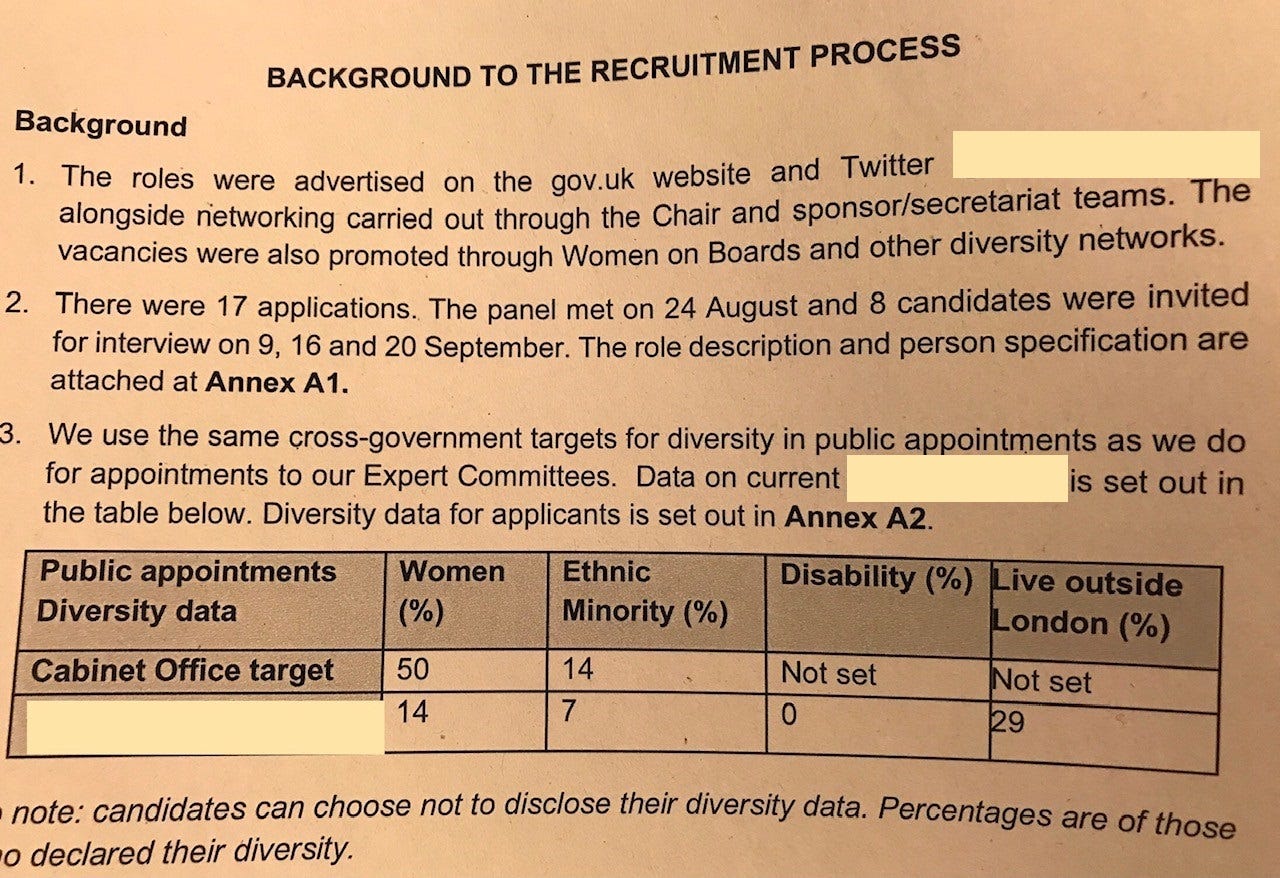

But they are far less often the focus. For example, when I was a minister, when making appointments I would be informed of our departmental targets for the representation of women and ethnic minorities (NB all minorities were treated as one homogeneous group). Although numbers of disabled people and people from outside London were monitored, targets weren’t set for these groups.

The case for and against

Many conservative-minded people (including me) feel mixed emotions about the drive to make things “more representative”.

On the one hand, many will feel sympathetic to attempts to encourage people to come forward to roles if they are being put off by misperceptions or historic problems.

On the other, they will feel very nervous about any shift away from the ideal of appointment-on-merit, towards quotas or policies that discriminate and might have harmful side effects.

In fact they may be more nervous about such moves now than in the past, because of increasing radicalism and a shift against meritocracy of the left. The administration of such policies adds costs and helps to build up a DEI bureacracy which may have wider negative effects. For example, the number of personnel in the MOD working solely on diversity and inclusion more than doubled from 20 at the start of 2019 to 50 last year.

The starting point

A crucial starting point should be that disparities are not on their own evidence of a problem. This is worth restating, as many organisations have drifted into assuming that anything other than a workforce which has the same proportions as the wider population is, on the face of it, a problem.

This is wrong. For example, men and women do have different interests, as well as different strengths. Different ethnic groups have different interests in both their private and professional lives. Few argue that it is a problem that there is a tradition of becoming doctors among British people of Indian descent. But if you accept that different groups interests may just vary, then it is not obviously a problem if a particular group are less interested in or less represented in a particular profession or group.

I went walking in the lake district with a friend from the far east a few years ago. She liked it but found the whole thing baffling. When we came to the first drystone wall she asked: “how are we going to get over this dam?” In countries where farming means paddy fields, there’s not the same tradition of roaming across the countryside.

Despite this there has been a whole rash of pieces about the “unbearable whiteness of hiking”, not least because clothing brand the North Face are funding a campaign to this effect. If people don’t do something, even if there are literally no obstacles to them doing it, this is seen as evidence of a problem, and indeed racism.

Arguments for policies to make organisations “more representative”

The two key arguments for these kinds of measures are:

1) An organisation may struggle to do its job well if it is not trusted by groups who are not represented in it. Two typical examples often raised are the old RUC in Northern Ireland, and black people in the police (in most western countries). The argument runs that unless the organisation is made more representative it will either actually be hostile to certain groups (“institutionally racist” police) or at least perceived as such. This means people will then not cooperate with them and they will not get intel or help to control crime.

2) Unless certain groups are represented within an organisation to a certain extent it will not be good at recognising certain concerns or needs or problems. While an organisation can make efforts to listen to a wide range of groups, it is more likely to pick up on particular problems or concerns if it also contains a decent number of people from different groups who are more likely to care because it affects their group more directly.

Arguments against policies to make organisations “more representative”

1) Moves away from meritocracy are unfair and lead to direct discrimination against members of other groups because of their skin colour or sex. It strikes at the hard-won ideal of equality under the law.

2) Not only is this directly unfair, but it also reinforces a trend to view people as members of groups rather than individuals. This has wider negative effects and takes us away from being a country at ease with itself.

3) Moves away from meritocracy are likely to hamper the effectiveness of the organisation. The further you go away from “the best person for the job” the higher these costs will be. While the negative impact of softer measures is lower, once you get into hard quotas for particular groups you are getting worse people who would otherwise not be chosen, and a worse organisational performance.

4) There are direct effects on the organisation from non-meritocratic hiring and also indirect: able people may leave and go elsewhere or reduce their effort if they feel discriminated against by these policies or won’t be able to have a fair chance of getting ahead.

5) Typical DEI type policies may have other undesirable side effects. For example, they may reduce viewpoint diversity. Policies to force up the numbers of one group may reduce another (more women and ethnic minorities, fewer older people or people from the north)

6) Policies are often pursued asymmetrically. Where groups with protected characteristics overachieve their share of the population in some prestigious domain where policies to boost their representation have been in effect, there is no action taken to reduce their share of the workforce. For example on TV, in 2021/22, about 8.1% of those who appeared were black. That’s twice the share of the population. No-one in the media will argue that their share should be reduced even though this would make TV “more representative”. This asymmetrical approach reveals that in many cases the motivations are not those stated above, but in fact based on more contentious and vague arguments about the “structural” position of certain groups: hazy arguments which many people would reject.

7) Policies can be in tension. Imagine you have a goal to drive up say the number of women and the number of people from a particular ethnic group. How are you to choose if you have a female candidate and minority candidate?

8) These categories can be highly subjective. People can self-identify as a member of a group for the purpose of statistics with few problems. But once group membership changes your chances of being hired the stakes are much higher. How are decision makers to judge whether you are or are not in a group? The fastest growing ethnic group in Britain is mixed race. This group will grow in future, and there will be more and more people with say, one ethnic minority grandparent out of four or one out of eight great grandparents. Should such people benefit from positive discrimination, and if so, why? Even something like sex which seems clear cut can lead to controversy where male-to-female trans people gain advantage from positive discrimination intended to benefit women.

It depends on the policies

It’s obvious from the arguments above that a lot turns on exactly what kinds of policies we are talking about, how far you take them, and to what end. I think there is a sort of spectrum here, from softer policies which I think are OK to “harder” ones - some of which I think should be illegal.

…The soft end

At the softest end, there are outreach programmes and measures to encouraging certain groups of people to apply. Examples: top universities spend some money encouraging people to apply from schools where there is no history of that happening. Before the point where I applied for University, I wasn’t aware that either Oxford or Cambridge were places particularly known for that sort of thing (my folks didn’t go) and focussed advertising and the like can open up new possibilities for people and groups of people who have never thought of such a thing.

The softest kinds of policy, in a situation where there was a real problem, might well be pro-meritocratic. You can imagine a kind of Laffer curve. If good people in certain groups are put off applying, a bit of deft outreach might get you better candidates.

However, there is a slippery slope here. These kind of arguments (“we’ll get better candidates”) continue often to be made where policies have escalated to a point where the costs are outweighing the benefits.

Then there are policies that are either pro-meritocracy or aim at least not to damage it: things like “Blind” CVs and moves towards tests rather than interviews. The main downsides of these things are (i) they can make recruitment processes more onerous; (ii) there may well be reasons to interview in later stages for jobs where teamwork is important and whether the new person will click with the team is important; (iii) in the hands of bureaucrats, formulaic or tickbox-y applications may select for some characteristics (conscientiousness, compliance) and against others (flair, originality). Against that, tests can be fairer: state school pupils lost out when tests were suspended in the pandemic. Some types of tests might be better than interviews: the Spectator does blind applications and tests writing ability, which is the main thing they need.

Then there are changes to practices and working patterns to make a workplace more attractive to some groups. One of the arguments for moving the House of Commons to what were called “family friendly hours” were that it would make being an MP more possible for women. It was a good idea. Flexible working is another example. But again, there are questions of degree. The opportunity to work from home might make a workplace more attractive to parents and carers – particularly mothers. On the other hand, should all Muslim office workers have the right to work from home throughout Ramadan? Many workplaces are navigating their way through this. I’m always amazed how much Muslim friends manage to do while fasting: I’d chew my hand off.

…The hard end

Where I part ways with this agenda is when it veers more sharply away from meritocracy.

Jobs, internships and scholarships where *only certain groups can apply*

Many prestigious organisations have routes into employment which are only open to certain ethnic groups. I say “routes into employment” deliberately, as many organisations seek to hit goals and quotas not directly by stopping people applying for jobs but by controlling thinks like internships, placements, scholarships and things that lead to jobs.

Often organisations are skirting the law. For example, the BBC advertised a 12-month trainee broadcast journalist job and said it was for BAME people only. A BBC spokesperson said: “This is not a job, but simply a training and development opportunity. This training scheme is designed as a positive action scheme to address an identified under-representation of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in certain roles. Such schemes are allowed under the Equality Act and we're proud to be taking part.”

For many years the Labour party has had a policy of “all women shortlists” for parliamentary seats (the policy was ruled illegal in 1996, and they had to retrospectively legislate to legalise it in 2002.)

Some versions of “only X groups can apply” are more opaque. For example, GCHQ asked people to register their interest for a job, saying this was “only open only open to those from an ethnic minority background or women”. GCHQ said that it was legal because the job was open to all, just not the registration of interest. Such opaque tactics are in practice pretty close to saying only some groups may apply.

Schemes where only some groups can apply are now widespread in the UK:

The Bank of England has internships only open to people from a black background - the “Black Future Leaders Sponsorship Programme.” Since 2016 the Bank has offered paid internships that are only open to black people.

KPMG have work experience placements for people of Black Heritage.

Nat West have the same.

PWC had an internship programme which banned white applicants (they have dropped it)

Transport for London have a Communications Internship which was only open to BAME people but now (following complaints) prioritises BAME people.

The Law Society’s Diversity Access Scheme

It has also become standard for British Universities to have racially exclusive scholarships:

Oxford University has scholarships only open to black people.

Cambridge University are offering scholarships only open to black people through the Stormzy / HSBC programme.

Imperial College offer scholarships, “exclusively for students of Black heritage”

UCL has scholarships for black and minority ethnic (BME) postgraduate research students. Pakistani and Bangladeshi people may apply, but not Indian.

The University of Bristol has the Black Bristol Scholarship Programme supporting around 130 Black undergraduates and postgraduates over four years.

A large number of other universities offer similar.

And after recruitment, within organisations, many corporates and government bodies have staff networks that are only for some groups. A good test of some of these things is to check how we would feel if the policy was reversed. For example, most government departments have ethnic minority staff networks. How would people feel about a network only for white staff?

“Decider” discrimination “where other things are equal”

In job adverts the City of Westminster council declares that:

“The Council is committed to achieving diverse shortlists to support our desire to increase the number of staff from underrepresented groups in our workforce. We especially encourage applications from a global majority background and, while the role is open to all applicants, we will utilise the positive action provisions of the Equality Act 2010 to appoint a candidate from a global majority background where there is a choice between two candidates of equal merit”

What does it mean to be of equal merit? I have done quite a lot of recruitment and anyone who has ever been through a hiring process will know how difficult it can be to choose between candidates. You can’t score people to the third decimal point. Most of the time you can kind of see that there are a couple of people who could do the job. In practice in the case of Westminster council, if two people can do the job, they will always choose the person from the “global majority” (I think this means anyone who is not white, but there’s no clear definition).

The shadow of this policy will hang over the decision-making process too - it is clear to recruiters that the council leadership want more “global majority” people. Achieving that strong political goal will have priority over worrying too much about who exactly is the best candidate, as long as they can more or less do the job.

Quotas

One step down from jobs where only some groups can apply are quotas.

For example, The Welsh Labour government is legislating to introduce mandatory gender quotas for Senedd elections. If a political party puts forward a list of two or more candidates in a Senedd constituency, at least 50% of their candidates will have to be women and all candidates on the list that are not women, must be immediately followed by a woman.

Most government departments have quotas, many large corporates too. Though slightly less bad than ruling out certain applicants up front, the effect can be the same in practice if quotas are being pursued hard.

As well as colouring the whole hiring process, quotas tend to lead to other policies and processes. It was in pursuit of quotas and targets that the RAF “paused” the hiring of white pilots, resulting in their defeat in court. Quotas and targets are also objectionable because they obscure the means that will be employed to achieve them. The setting of a quota or target is a promise that an organisation will do undefined “stuff” to make sure that we have the “right” number.

And the numerical targets are often pretty arbitrary. Racial targets often lump together groups with very different prospects into one monolithic “BAME” group (sorry, “Global Majority”). Targets for women (51% of the population) might seem simpler, but how should an organisation determine how much of a disparity can be explained by preferences or the composition of potential applicants rather than discrimination which might be offset by positive discrimination?

Our children quite like to go on our local steam railway. I have noticed that people enthused by steam trains are not exclusively but disproportionately male. People are not worried by the idea that different people might like or aspire to different things when the examples are low stakes. But the same forces and preferences do also apply to the jobs and courses people apply for. Example: kids from families with a tradition of service in the forces are more likely to go into the forces. People whose families have been in the UK for longer are more likely to have such a background. I have known people from all ethnic groups who have loved being in the forces (or wanted to be). But it is possible that different groups might have different preferences.

In an interview in January Grant Shapps told the Telegraph:

“Something which I’m extremely passionate about is actually having a military which should represent our country as it is today. It can’t be right that our military still only has 11 or 12 per cent women, for example, when you make up half the population.”

Shapps is doing brilliantly and has managed to secure a large increase to the defence budget, and is cracking down on various forms of woke waste. But I was struck by this comment. What is the evidence that 12% is the ‘wrong’ number and should be higher? In many militaries around the world this would be seen as very high. It is well evidenced that men are more violent and more interested in the military. What is the evidence that the current percentage is evidence of a problem, and the evidence that this causes such harm that hard-edged policies would be justified to tackle them?

As David Goodhart has pointed out, there is a paradox here:

“On the one hand, multicultural democracies encourage people to celebrate and affirm their group identity — the traditions, practices and priorities that make their group different. On the other, we regard with suspicion and alarm any significant differences in average outcomes — for example in educational or economic success — that might arise from those same group practices and preferences” […]

When such group differences contribute to positive outcomes, such as the fact that around 30% of NHS consultants are British Indians, it is attributed to the group’s drive, energy, focus on education and so on. But when minority groups have negative outcomes — when they are over-represented in the prison population, the unemployed or the poor — race justice campaigners tend to default to white racism as the explanation.

What’s reasonable depends on what the evidence of a problem is

I said earlier on that I’m not an absolutist about these things.

Very occasionally, if the logic and evidence is strong enough, I can see the case for some of the harder edged policies here - for example, Catholics not wanting to join the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Northern Ireland.

The reboot of the RUC involved not just a new name and badge, but an aggressive (temporary) positive discrimination programme (50:50 recruitment) designed to show that the service was moving on from previous failed attempts to get a more religiously balanced workforce. There were people who lamented this as a concession to republican violence, but it was hard to argue against the idea that perfectly capable Catholics were put off joining by the history and reputation of the force. It is not the case that Catholics worldwide hate being police officers. Yet only 8% of RUC officers were Catholic in 1997, compared to 40% of the population. (About 26% of the PSNI is Catholic in 2023.) It was clear why they were being put off and the wider benefits to the peace process were significant. It was right to give the RUC the George Cross for bravery in policing an impossible situation, but also right to replace it with the PSNI.

In contrast, too often we see targets set and policies put in place without a clear logic which sets out (a) proof that disparities are not just the result of preferences and (b) proof that the disparities are causing real world harms. On the basis of flimsy evidence organisations are adopting hard-edged policies involving direct discrimination, which is unfair, and may have wider negative effects.

Conclusion

With the possible exception of acting roles, I think that policies where only some groups of people can apply should be illegal. They are allowed under the positive discrimination provisions of the flawed 2010 “Equality Act” but should not be.

I think quotas and targets should not be allowed unless in truly exceptional circumstances like those in Northern Ireland. Too often they are being used without a clear logic or evidence. And I don’t believe that “tie breaker” policies are likely to be enacted honestly - I think they will collapse into positive discrimination.

Not that long ago US-style positive discrimination was regarded as weird and wrong in the UK. But we seem to be drifting into it, without really thinking about it.

Spoof Twitter personality titania McGrath has an ever-growing list of Things That Are Racist

Thank you Neil O’Brien for another well written article. I may be biased since I usually agree with your conclusions. Would it be possible for you to write something on the economic effects of Brexit?

It is astonishing how the English have relinquished this land. There are few cases of a voluntary hand over such as we have seen, it is almost unprecedented.

See https://therenwhere.substack.com/p/why-did-the-english-self-destruct

I got called away so did not finish the above comment.

I should have added that by 2030 the English are inevitably destined to be a minority in England because migrant children will be the majority population in schools.

I should also have pointed out that your piece can be summarised as:

"government should guarantee that no group is able to reserve economic activity to itself either deliberately or by accident."

This belief is the reason the English self destructed. It is a very strong philosophical/political position about power in society. It is the viewpoint of Internationalists, large corporations, International Marxists and the British Labour and Conservative Parliamentary Parties. Though probably not the viewpoint of a lot of people.

The West has this belief but in many countries it is regarded as obviously false. Countries that hold the belief will disappear given long enough. They will self destruct like England. Demographics mean this is inevitable.