More on the post study work visa

On the link to research, low earnings, and the problems with the quasi-market

The government has decided to sharply cut student migration. Ministers are concerned about the impact of record migration on house prices, and widespread abuse of the system.

Sound familiar? Actually, the government I’m talking about is the Australian government. They’re bringing in stricter English language tests and requiring students to have much larger savings to show that they can support themselves1.

The Aussies aren’t alone. In January the Government of Canada announced it would set an intake cap on international student permit applications. The cap is expected to result in a decrease of 35% in the number of students compared to last year. Again, record numbers and housing pressures are among the reasons.

In the UK we are still making up our minds. There’s been lots of back and forth about the two year post-study work visa (the “graduate visa”) over the last week or two following the MAC “Rapid Review”, which I wrote about before.

I thought I would pick up some of the issues that are being raised in one place.

Let’s be clear what the sector is asking for

It is worth being clear about what the universities are lobbying for here. A number of people have tried to imply that this is about whether students from overseas can come here or not.

Nope. What the sector is asking for is not just for students to come here.

What they are actually asking for is for the government to bundle a two year unrestricted UK work visa with the degrees they sell. That was the change made in 2021 when the post-study visa was re-introduced.

To put it bluntly, universities want the government to sell work visas in order to benefit them. This is the recent change which the government is mulling, not whether students can come.

Selling an unconditional work visa to the UK is worth quite a lot of money. As the Migration Advisory Committee pointed out:

In the case of an international student studying a 1-year postgraduate Master’s, and bringing an adult dependant, the couple could earn in the region of £115,000 on the minimum wage during the course of their 3 years in the UK. Some universities offer courses at a cost of around £5,000.

Minimum wage work in the UK isn’t that attractive to people from developed countries, but is very attractive to people in low-income countries. That’s why the turning on and off of post study work visas has not changed the number of students coming from developed countries, but has changed it a lot for those from poorer countries:

Study and stay

As the chart above shows, the existence of the post study work visa changes who comes as a student.

If we look at the cohort of students who came between 2007 and 2016, Only about 6% of students from the US were still here in with valid leave in 2022, but it was between a quarter and a third for countries like Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Now the post study work visa has swung student migration towards these countries meaning stay rates will likely be much higher.

Thursday’s new Home Office data should tell us more. The post study work visa came in part way through 2021, and we can see from the Migration Observatory chart below it that already led to a huge increase in the proportion of students switching into work within their first year here - roughly half the 2021 total below is the post study work visa.

Low earnings

Some supporters of the post study work visa have wanted to dispute the data on the low earnings of the people on the route. For example my former colleague David Gauke - who I like a lot - wrote on Conservative Home that:

In the first tax year in which someone with a graduate visa works for more than a month, 41 per cent earn less than £15,000. But if a graduate starts work in September and the tax year runs to early April, this number is not altogether surprising.

David isn’t alone in making this mistake: several other people have argued that quoting this number is unfair, because people are graduating part way through the tax year.

They’re wrong: the data in the report isn’t looking at people who graduate part way through the tax year. That £15,000 figure is referring to people who graduated earlier and could have worked for the whole tax year. As the text of the data report says:

“All figures and tables in this section relate to the PAYE reported gross earnings of main applicant Graduate visa holders who were aged between 18 and 65, whose visa was granted before the start of the period being looked at (and who had not switched onto any other visa type during this period)”

The report notes that for those in their first year on the post-study work visa:

“41% of Graduate visa holders who earned in at least one month in financial year ending 2023 earned less than £15,000.”

“The median annual earning for the 73% of Graduate visa holders who were in employment for at least one month in financial year ending 2023 was £17,815.”

The post study work visa is a type of work visa. And to put these numbers into context, the normal minimum general salary threshold for Skilled Workers is £38,700.

This is to try and ensure that we get higher skilled migrants: something politicians have promised for decades. But the median person on the post study work visa earned half that minimum requirement in their first year on it.

You asked, we answered

There was an interesting exchange about the MAC report at the Home Affairs Committee. Professor Brian Bell made it very clear that the MAC report answered a very specific question, and made clear that if they had been asked a different question, they might have given a different answer:

James Daly MP: there must be a point in terms of adding to the skills base of the UK labour market, adding to the economy and the value added. Now, I have looked at your report, and it seems to me absolutely crystal clear that the graduate route does not offer any value to the skills of the UK labour market at all, does it?

Professor Bell: That is broadly fair, in the sense that had we been asked the question by Government, “Do you think the graduate route is necessary, in addition to the skilled worker route, to bring skilled work into the UK?”, our answer would probably have been that the arguments are less compelling. That was not the question the Government asked us.

Bell also noted that:

“Our conclusion was that the graduate route was fulfilling the objectives that the Government had set for it in 2021 when they introduced the measure in Parliament. The Government’s objectives were to increase the number of international students who studied in the UK, consistent with the international education strategy of having 600,000 students in the UK.”

In other words, if the government’s main goal is just more overseas students then bundling with each degree a post study work visa certainly helps. Yes! Obviously!Whether that is a good idea is another question, given politicians have spent the last 30 years promising that they would aim for high wage migration.

Do universities need post study work to survive?

A lot of the debate about the post study work visa has really been a proxy for a wider debate about the financial position of universities. Common claims being made are that:

Without it, research activity will shrink.

There’s no alternative to the post study work visa unless the government will pump a lot more money in. Universities will shrink and this will be bad for the economy.

Let’s have a look at these claims.

Research

In theory universities can make a profit on overseas students, which they can then use to cross-subsidise research, or perhaps the tuition fees of UK students.

Numbers of overseas students rose steadily in the years where we didn’t have the post work study visa, so it’s not obvious that they need this in order to grow, particularly as Australia and Canada are cutting back numbers.

Obviously quite a lot of tuition fees are eaten up providing the actual course, and data on profit margins seems to be very limited.

And in so far as they do make a profit, that money could end up being spent on many things within the university. That could include research, but it could also go on lots of other things.

One problem is that the post-study work visa has mainly boosted overseas student numbers in universities that don’t do a lot of research.

In 2021 the UK spent £66.2 billion on Research and Development2. £5.6 billion of this (8%) was funded by Higher Education. The biggest spender was private business at £38.7bn. Government and its research councils, together with overseas investors funded most of the rest.

How has Higher Education-funded R&D grown over recent years? There is comparable data from 2018 to 2021. That means it is a bit early to be too definitive, but the trends undermine the idea that the post study work visa is going to deliver a research boom.

In 2017 the government set a goal to drive up research funding (Full disclosure: I worked on this in Number 10).

In real terms (in 2021 money) R&D funding by government, its research councils and UKRI increased from £11.5 to £12.8 billion from 2018 to 2021 - an 11% increase.

Real business funding of R&D increased 5%.

But real funding from Higher Education remained flat as a pancake, at £5.6 billion. Zero real increase.

And this was over a period in which total student numbers increased 17%, and the number of overseas students increased 37%.

So it’s not obvious that driving up student numbers is the best way to drive up funding for R&D.

Sure, you can always argue things would have been worse otherwise, and we don’t know the counterfactual. But many people are arguing oversees fee income means a great bonanza for research. That doesn’t seem to be the case.

One reason may be that research is highly concentrated within research-intensive universities and the growth in student numbers since the introduction of post study work has been focused on non-research-intensive institutions, which are mainly teaching institutions.

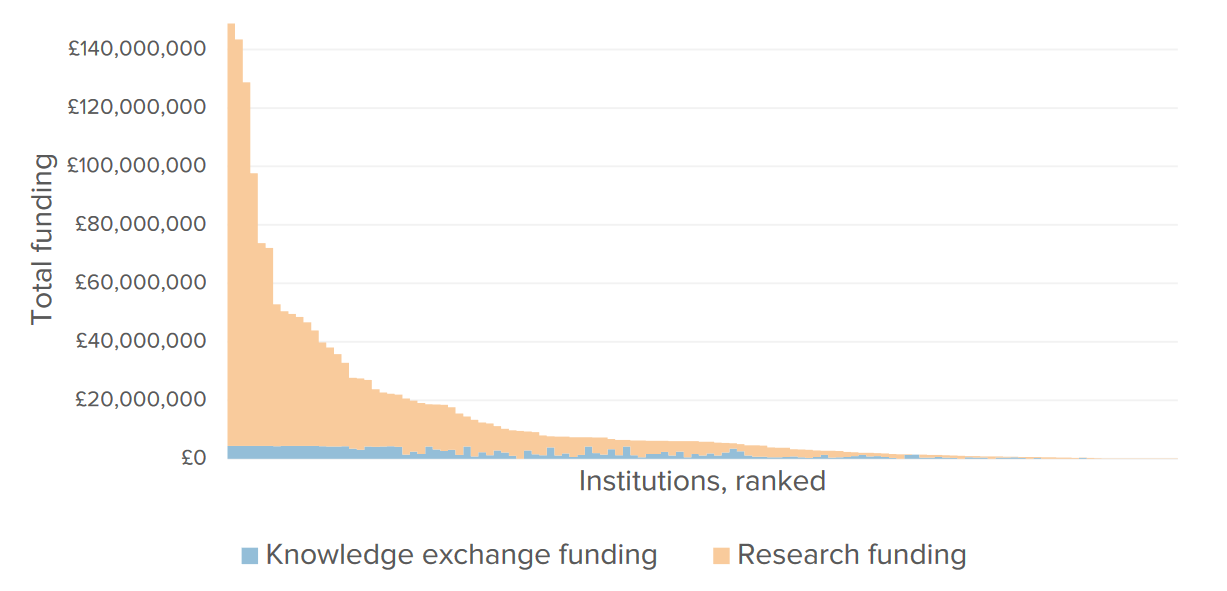

To see how concentrated, here’s is a chart of the allocation of Quality Related (QR) funding by individual university, ranked from the biggest allocation to the smallest.

Looking at QR funding specifically, in 2018/19 a third of QR research funding was spent in the top 4 institutions (Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Imperial). More than half the budget was spent in the top ten institutions, leaving 48% split between the other 115 institutions which received funding.

Did the grad visa boost research universities? The MAC have noted that

Since 2020 there has been a notable increase in the proportion of international students attending non-Russell Group universities. This divergence away from previous trends has almost exclusively been seen in postgraduate study and predominantly on 1-year taught Master’s programmes.

The trend growth in students is almost unchanged for Russell Group unis: people want to study there anyway. The post study work visa has had its effect elsewhere, leading to an explosion in numbers at non-Russell Group universities:

Figure 3.7: International students by type of institution

The MAC have also noted that:

the growth of international students studying taught postgraduate degrees has predominantly been in institutions that charge the lowest fees

And that

Similarly, growth in international postgraduate students has been strongest at the less selective universities.

All of this may help to explain why growing numbers of international students don’t seem to be translating into extra investment in R&D so far.

Is there no alternative? What will happen to unis without post study work visas?

On this final point, a lot of people are arguing past one another, and there’s no way to really explain without going a bit deeper.

A) The context: rising numbers and spending

The number of people going to universities in the UK has exploded over my lifetime.

The proportion of British kids going rose from 3.4 per cent in 1950, to 8.4 per cent in 1970, to 19.3 per cent in 1990 and 33 per cent in 2000. In September 1999, Tony Blair set a target to get to 50 per cent, which we reached in 2018.

Numbers from overseas have also grown, both absolutely and as a proportion - from 11% when Tony Blair came to power to just under a quarter (24%) now.

The growth in student loans has effectively given the universities their own special tax. This is much like the BBC licence fee, but much bigger - we will spend about £20 billion on student loans this year, rising to £24 billion by 2027.

This has allowed the unit of funding to be raised above the levels of the 1990s, even as numbers have grown dramatically.

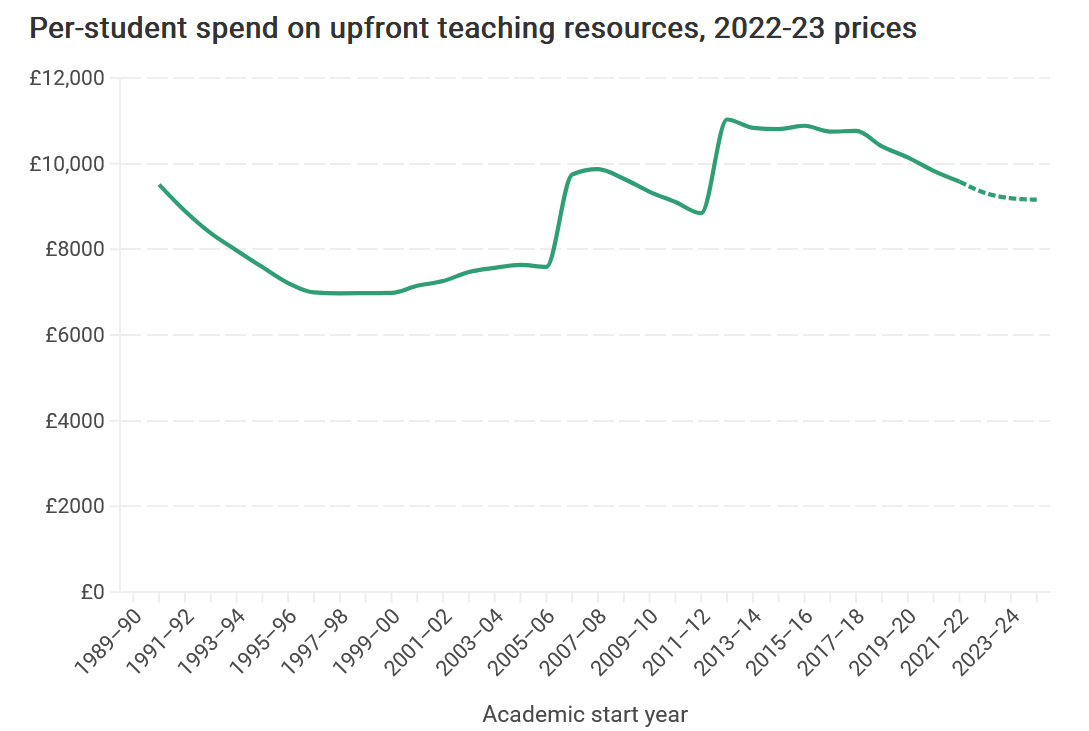

The IFS chart below shows that recent inflation is eroding away spend per student in real terms.

But it also shows that spend per student remains higher in real terms than it was in the pre-fees years, even though student numbers have massively increased.

I am very sympathetic to universities, but we should also recall that their special tax has given them a much better financial deal than many other important public services, during an era where the public finances have been battered by the financial crisis, covid crisis and Ukraine crisis.

B) The quasi market has not worked as hoped

The shift to fees was supposed to create a lively market in which competition would keep fees down and drive standards up. Fees would vary between different institutions, students would choose the best courses, and market forces would win the day. Hurrah!

Things haven’t turned out that way. Universities all immediately started charging the full amount. Standards have been debased, as universities chase fees. The share of degrees awarded as firsts has exploded in a frenzy of commercially-motivated grade inflation:

And it turns out that if you ask 16 and 17 year olds to choose subjects, in a context where they will only be charged much later in their life; and they know that they won’t repay if they don’t earn; and they don’t really have any information about earnings then, well… this doesn’t create the perfect market that some hoped.

c) Not all degrees are a good investment, and significant amounts of money are being wasted from an economic point of view

The Institute for Fiscal Studies have done a series of reports on the impact of the new system using linked tax and degree data in the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) dataset.

One of the papers looks at how much graduates on different first degree courses earn compared to similar people with a similar background and achievement who did a different course. They then compared this premium (if there was one) to the cost to the student and taxpayer to work out the net benefit.

They concluded that viewed from the point of view of the taxpayer, the taxpayer makes “a loss on the degrees of around 40 per cent of men and half of women.” Summing together the effect for society as a whole (the gains to students and taxpayers) “total returns will be negative for around 30 per cent of both men and women.”

In other words, nearly a third of students’ undergraduate degrees are not worth it economically - and these are concentrated in particular subjects like creative arts degrees, English, Languages and Physical (e.g. sports) sciences.

IFS have also look at Postgraduate degrees, which are a bit of a washout in economic terms:

We investigate the returns to postgraduate degrees by people's mid-30s. On average, they are shockingly low - the returns for Master's and PGCEs are close to zero for both men and women by this point… many Master's degrees do not boost earnings at all - for men, only engineering, economics, business and law have a significant positive effect by age 35. Many Master's degrees significant worsen earnings by age 35 on average,

In a report on the returns on different subjects they note that

We find massive variation in returns to degrees, even for those that are relatively similar in terms of selectivity. High returning degrees are difficult to predict from things that are observable to students when making their choices, such as league table rankings.

Since 2018 the ONS has taken a better and stricter interpretation of how it scores spending on higher education. Prior to that it had been rather like PFI, with spending off balance sheet. When they brought the costs on balance sheet, it added £10.5 billion to measured government borrowing in the first year, 2019.3

The new ONS measure means that a worsening of expected repayment rates directly costs the government more. The information from the same LEO dataset the IFS are using feeds into forecast losses. Action to improve repayment (e.g. by weeding out weak courses) saves the government money which it can put into other investments.

This is one reason the Treasury significantly tightened repayment rules in 2022: freezing fees; lowering the rate at which repayments start to £25,000; freezing it there till at least 2027; and also extending repayments to 40 years after graduation. Even so, write offs are still very large - over a third. Writing about the changes, the OBR noted that:

“In terms of the ‘RAB charge’ recorded in the Department for Education’s accounts in respect of future write-offs, this reduces it from 57 to 37 per cent in 2026-27.

So my first port of call to improve the financial position of universities would be to reduce the number of courses that don’t make economic sense, and recycle the savings into other more productive investments - including better university courses.

Universities have had a good run. Times Higher Education reported this year that Average vice-chancellor pay has increased to £325,000. Across the country universities have put up shiny new buildings. That’s great, but not every degree they teach is a good investment for students or taxpayers. Yes, some lossmaking degrees have intrinsic value, but so do many other things we can spend money on.

d) How to find money for useful courses

George Osborne got rid of the caps on numbers on different courses, and the fees-based system reduced ministers’ control in other ways too. In real terms (2021 prices) in 2010 the government gave universities £6 billion in teaching grants plus £3 billion in fees. By 2021/22 that had flipped around to 1.2 billion in grants and £10 billion in fees.

The current quasi market has given universities a big incentive to grow the numbers on arts and humanities courses which are cheap to deliver, to generate profits which they can re-deploy elsewhere. This is one factor which has both promoted the growth of lower value courses, and also made reducing their number more complex, because of the web of cross subsidies.

So far the DFE have not really taken action to try and squeeze down the number of lower value courses. I think they are still doing research on the issue. We need to crack on.

The government / Office for Students should do deals institution-by-institution to reduce expected losses by shrinking lower value courses. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think we should stop subsidising every arts course, but I also don't think we should have five times as many creative arts graduates as mathematicians.

I love universities. I was the first generation into my family to go, and it was amazing. Unis do many great things. But politicians have to balance that against other massively important promises to the electorate, and other important services voters value.

There is untapped potential to do more and do better with existing HE funding, and the university sector won’t go bust if we get rid of the post study work visa. They didn’t last time, and wouldn’t in future.

The UK used to have similar requirements but got rid of them at some point in the Blair era.

Some people might assume that the R&D we are measuring here is unfairly narrowly defined as particle accelerator stuff, but the OECD Frascati measure being used here is very broad: it includes spending on social sciences, arts and humanities too.

The IFS have put forward quite a compelling argument that we still aren’t measuring the full costs because the ONS measure does not take the cost of government borrowing into account at all, and global rates have gone up.

My understanding (perhaps erroneous) of the work visa was that it was partly intended to attract "students" to fill the huge gap in care home staffing levels? If this is correct, does the Govt. have a system to adequately check the credentials of those "students"? My personal experience of the sudden huge influx of Africans as care home staff suggests that a significant proportion of them would not be capable of post-degree, or even degree level study. Going by the UK's dubious immigration control history, it would not be surprising if these checks were less than rudimentary, such is the desperation to fill this void (greatly exacerbated since Covid).

In January the Canadian government EXTENDED their post-study work offer for international master's students, allowing graduates to stay in Canada for THREE years after graduating. So using Canada as a case study when arguing the UK should cut it's post study work offer is ... strange. https://getgis.org/news/canada-extends-work-permit-for-masters-students-to-3-years

Canada's cap is also only for undergraduate students. It's been introduced because their universities have taken liberties with 'franchising', setting up low-quality franchise campuses to heavily recruit undergraduate students who wouldn't have the academic credentials to get into a regular university. Franchising in the UK might have issues, but nowhere near the scale seen in Canada.