Migration and ethnicity: part one

The scale of the change & the geographical variation

It seems to turn on where you are. Or who.

- Philip Larkin, “Party Politics”

Years ago, when I was working with street homeless people in London, we met a guy who was sleeping rough in Whitechapel. He was in a bad way, but only had enough English to tell us he was Kurdish. We were a bit stumped. What on earth were we going to do? But this being Whitechapel, the problem quickly resolved itself: another Kurdish guy walked down the street and we roped him in as a translator.

Several years later I was chatting to one of my most affluent friends, who told me that “immigration hasn’t changed the country.”

Both these moments point to one of the striking things about migration: the effect is hugely variable between different places, and different people’s experiences of it are wildly different. For some people immigration hasn’t really changed their world. For others, it has absolutely transformed it.

This is the first part of a two-part post. The second part will look at the radically divergent experiences and economic outcomes of different groups of people who have come to Britain.

In this first part, I will look at the sheer scale of the change, and the degree of variation between different places in the UK. I will look at data on both (a) migration and (b) ethnicity, and I’ll try and be as clear as possible when changing from one to the other.

To examine the change I’ll look at data from the census, schools data, and data on births. (Sadly, quite a lot of the data will be for England and Wales only, as we are still awaiting detailed results from the Scottish census 2022, and schools data is also fragmented.)

I’ve written a couple of pieces so far about the economics of migration, and what I think we should be aiming for, but clearly the migration debate is about more than just economics.

Whether it is low rates of vaccine take-up among some ethnic minority groups, or the Michaela School legal case, running a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society obviously brings with it new challenges.

My basic take away is that the change in the country over recent years has been enormous, unprecedented, but also very unevenly spread. This causes people to talk past one another when discussing migration. For some people, their Britain is not much changed. For others, it’s been multi-ethnic as long as they can remember. For others it is changing very fast around them.

How have levels of migration and ethnicity changed over time?

Every ten years the census records what proportion of people were born overseas. Since 1991 the census for England and Wales has also collected data on ethnicity, and it has done so on a consistent basis since 2001. The share of people in England and Wales born overseas, (just under 17%), has now overtaken the USA, (13.6%) despite the perception of America as a “melting pot”.

The data also shows the acceleration of migration over the last 20 years. Migrants also have kids (obviously), and so the proportion of people identifying as non-white British has grown faster than the share of people born overseas.

Estimates of “net migration” are often quoted, but this doesn’t fully capture the churning effect on communities of immigration and emigration.

In 2022 around 1.2 million people came to the UK, while nearly half a million left. Depending on your point of view you could see this churn as the mark of a dynamic society, or as creating less settled, more transient communities. Or both.

Either way, the net effect has been a dramatic acceleration of net migration. The headline figures which are generally quoted are the light blue line, which includes the effect of the net emigration of British citizens. Excluding British citizens, the figures for the sixties and the noughties are quite a lot higher, as net emigration of British citizens was particularly high during those periods.

Digression: The missing million

How many people have migrated to the UK in the last 20 years? In theory this sounds like an easy question to answer - but the two main sources of data give radically different answers.

According to the 2021 census for England and Wales, out of a population of just under 60 million in England and Wales, 10 million (or just under 17%) were born in another country.

Of these, around 6.9 million said they arrived in the UK between 2001 and 2021 - so just under 12% of the population.

BUT this census figure for England and Wales alone is quite a lot higher than the cumulative figure for net migration to the UK as a whole. How can this be?

ONS net migration statistics say that from the start of 2001 to the end of 2021 net migration to the UK was 5 million. Part of the difference between this and the 6.9 million is because the headline net migration figures that are most often quoted include the offsetting effect of the ongoing net emigration of British people.

If we exclude Brits, then net migration to the UK was 6.3 million (12 million immigration, minus 5.7 emigration). ONS estimated in 2021 that 94% of migrants to the UK were in England and Wales, so that would mean ONS net migration of about 5.9 million to England and Wales - a whole million lower than the census figure for the same period.

Some of the gap may be explained by people being wrong about when they first came to the UK, particularly if they have gone back and forth. But it may well be that we are (still) undercounting net migration.

Personally, I suspect that’s probably the main factor. Given that we all scan our passports, many people are surprised that migration statistics are not based on counting people in and out of the country. For the years before 2012 the statistics are based on the International Passenger Survey (literally people in airports with clipboards trying to get people to speak to them). Since 2012 ONS produces statistics based on administrative data, which are a complex work in progress and have the status of “Official Statistics (in Development)”.

We have been wrong about how many people are here before: the Home Office impact assessment for the EU settlement scheme estimated that between 3.5 and 4.1 million EU nationals were in the UK, and would be eligible. But a much larger number - 5.7 million people - have now received a grant of settlement: so our understanding of how many had come to the country was about 50% out! So I think the census, where we literally count everyone, is our best source for understanding what’s going on.

Digression over!

Where did people come from, and when?

Unlike net migration data, the census lets us see exactly which countries people have come from, and when they came. India is the biggest country of birth for those born overseas. The chart below shows the largest countries of origin: people from countries like Poland and Romania have typically arrived more recently than those from India, Ireland or Jamaica.

Where in the country did people migrate to?

The map below looks just at recent migration - those who arrived between 2001 and 2021 - and is broken down by parliamentary constituency. Just under 12% of people in the census for England and Wales said they arrived between 2001 and 2021, but this migration was very unevenly distributed around the country. While many shire and coastal constituencies had less than 5% of the population who had arrived since 2001, many London constituencies had more than 30%.

The same was true for some places like Birmingham, Leicester and Manchester. This is obviously relevant to the debate about housing and migration: the impact of new arrivals is highly concentrated on particular housing markets. In Staffordshire Moorlands just 1% have arrived since 2001, whereas in the Cities of London and Westminster it’s 41%. This is obviously pretty relevant to London’s housing issues.

What is the ethnicity of people in different places?

Like migration, ethnicity varies massively by constituency. On the one hand there are 47 seats in England and Wales where less than 5% of people are non-White British; and on the other hand, there are 39 seats where more than two thirds are. To pick two seats at random, in Richmond, North Yorkshire under 6% are not white British. In Holborn and St Pancras, nearly 64% are. In Wales and the North East over 90% are White British, in Greater London it is just over a third (36.8%).

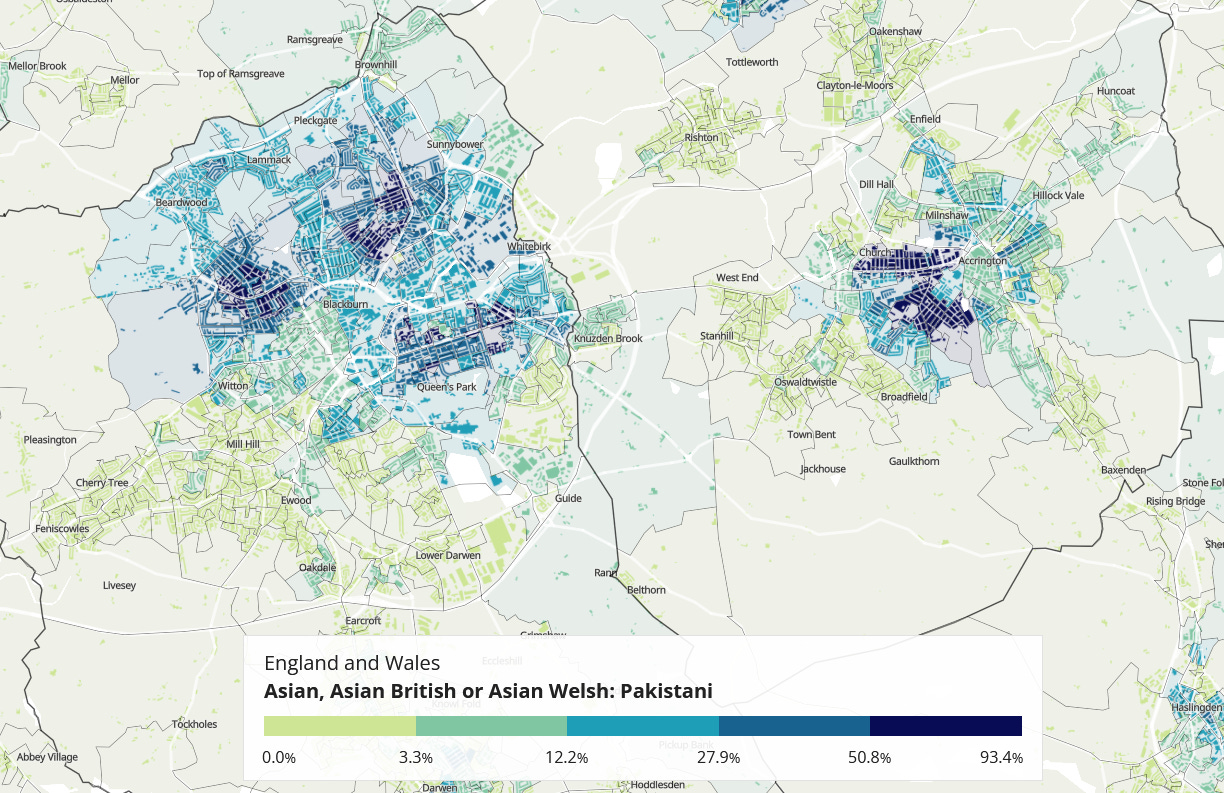

The variation is even greater at the neighbourhood level. The ONS has an amazing data explorer map tool which allows you to zoom in to neighbourhoods. The degree of variation within towns and cities is enormous. Cities and towns in the north and midlands have neighbourhoods that are entirely white, and others that are almost entirely composed of particular ethnic minority groups.

This is one reason people’s experiences are so different, even within a single town. I used to get the bus to school in Huddersfield and pass a large piece of graffiti above Fartown saying FREE KHALISTAN, and I used to wonder where Khalistan was. (As an MP for the southern part of Leicester I know much more about it.) But even somewhere like Leicester, which people often think of as majority Asian, has massive variation within it. In the suburbs, 90% of people are white British: in east Leicester, less than a fifth.

This variation is often cited as a problem when there have been disturbances with a racial edge, but of course there are strong, rational reasons why people want to flock together - as my Kurdish experience at the top exemplifies. British politicians have never wanted hard-edged policies to prevent segregation, or force integration. The only example I can think of is a proposal in the 1960s to control where people could get mortgages, in order desegregate ethnic minority groups - slightly surprisingly that was a proposal put forward by Ken Clarke and others.

How wealthy are the places people migrate to?

The second part of this post will look at the economic outcomes and experiences of different migrant and ethnic groups. But it is worth noting here that the places people generally migrate to are poorer than average: typically, poor urban areas. This is one reason the effects of migration were less visible to my very affluent friend, and potentially to elites generally. About two thirds of all post-2001 migrants live in the more deprived half of neighbourhoods.

How old are migrants and members of ethnic minorities?

It isn’t just where you are. As Philip Larkin’s poem at the top says, your experience of migration and ethnicity depends on who you are, and in particular how old.

Most people migrate in their working age. So among people aged 35-45 in England and Wales, about 30% were born outside the UK. But for babies and older people it is much lower.

We see the same thing with ethnicity. This is partly because of the direct effect of migration above, and partly because migrants make up a bigger share of parents than their share of the population as a whole.

I am 45, and so am at the turning point of the chart below. Among people my age or younger, two thirds of people in England and Wales describe themselves as white British, compared to 90% of those aged 65 or over.

The relative balance of Asian and black people in the chart above might surprise someone whose only knowledge of Britain came from television. On TV, in 2021/22, about 8.1% of those who appeared were black, while about 4.9% were south Asian. This is roughly the opposite of their real-world shares of the population of England and Wales, where 4% are black, 6.9% are from south Asia (India, Pakistan or Bangladesh) and 9.3% are Asian.

So far, we’ve looked at the impact of age, and migration and ethnicity separately. When you combine multiple dimensions of sorting effects the variation is greater. So, for example, a working age Londoner has a very different impression of the country than a retired person in the North East.

Schools data

I am grateful to DFE for the data below, which I got in response to a WPQ (I think it is the biggest file I’ve ever been sent in answer to a WPQ.) The dataset shows the ethnic breakdown of every school in each academic year between 2006/7 and 2022/23. Unfortunately, it just shows ethnicity, not migration.

Schools data has two benefits. First, the demographics of our schools give an insight into the future of the country and different places in it.

Second, it’s difficult to compare small areas between different census years, as the census geography of neighbourhoods changes (the boundaries of OAs, LSOAs move around). But one source of data that can serve as a fixed point to measure small areas over time is schools data, because schools don’t move around.

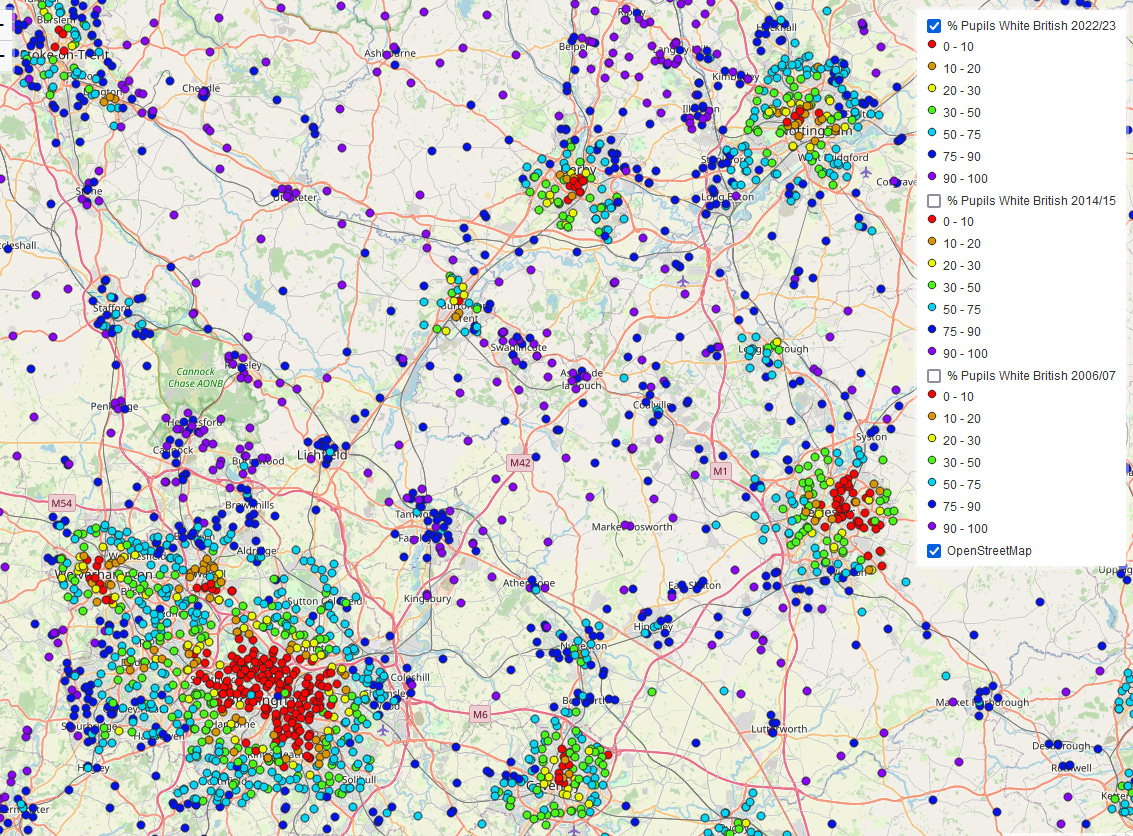

Overall, the change is very dramatic over quite a short period. The proportion of schools where white British pupils are a minority increased from 12% to 23% over the period. The number of schools where white British pupils accounted for less than one in twenty pupils rose from 421 to 872.

But again, how and whether you experience the change depends on where you are.

Datawrapper doesn’t like the idea of plotting all 31,000+ primary and secondary schools, so the first two interactive maps here are aggregated up to current parliamentary constituencies.

The first map, below, shows the current mix of pupils:

The second map shows the change. I think it is interesting that many of the biggest changes (in absolute terms) have been around the capital, rather than in it. The proportion of pupils who were from ethnic minority groups was already very high in inner London, so had less scope to change, compared to Dartford, Wokingham, Watford, etc.

Over the period the proportion of pupils who were white British fell from 38% to 23% in Greater London. But that change was concentrated in outer boroughs, and similarly rapid in neighbouring districts just outside London. Elsewhere the picture was different, and the biggest changes were in the centres of cities: in Nottingham, Coventry, Sheffield, Manchester, Leeds and so on.

The same pattern is apparent if we look at some of the most changed schools - they are in outer London, but city centres elsewhere:

If you teach in or lead a school where things are changing fast, you may have to change your arrangements, assumptions and teaching style over a relatively short period:

Because Datawrapper won’t let me plot c. 20,000 schools at one, I have posted the data on a stand-alone map, which you can play with by clicking here. (it may take a moment to load and is better on a computer, not mobile). Using the dropdown menu you can choose between years to see how schools in your area have changed between 2006/7 and 2022/3. You can scroll and zoom to look at your old school. To include some static maps, here is what London looks like:

London in 2006/7:

London in 2022/3:

The schools data also shows us the incredible degree of variation between our cities and shires - and indeed within our cities. Here’s the cities of the midlands: Birmingham is bottom left, Nottingham is top right. Within cities in the north and midlands, you can see that pupils in the same towns and cities are experiencing very different social worlds.

Because people cluster with people like them, a pupil population that is multi-cultral overall in a place, doesn’t mean all schools are multi-cultral.

In London there are 128 schools that are majority black, 239 that are majority Asian, and 283 that are majority white British. In Blackburn, out of 67 state schools, 27 are majority Asian, 36 are majority white, and a smaller number have an even mix. There are a further 6 Islamic private schools on top.

These changes in schools obviously pose all kinds of challenges, and there has been plenty in the papers about them. Whether it is the campaign of threats against Barclay Primary, or the Batley Grammar teacher in hiding after death threats, or the row at Kettlethorpe High School, or the Trojan Horse row, or the row after pupils in Pimlico took down the Union Jack and forced the head to resign, the mass brawl between Slovak Romani and Pakistani pupils in Fir Vale, Sheffield… the list goes on. It isn’t easy in some places.

The Michaela School legal case showed the tricky balancing act more and more schools have to perform to keep pupils rubbing along: managing sensitivities over holidays and timings; over food (vegetarian to avoid rows); over what can be taught; and of course, over religious observance.

Maybe the most obvious challenge in schools is the growing number of pupils who don’t speak English as their first language. While children’s ability to catch up is always amazing, this often requires a lot of resources, particularly in primary schools. There are about 1.7 million pupils in state schools in England who don’t have English as their first language, and the proportion has increased substantially over time:

Again, the variation is massive, from just over two percent with English as an additional language in some constituencies, to two thirds in others:

Births data

Last but not least, it is worth looking at data on births. Births data in a sense lets us look even further into the future of the country than schools data. Births data also gives us a sort of measure of integration, by showing how likely people who have come from other countries are to have kids with people from the UK, or to have them with people from their own country of birth.

The overall trend is towards falling numbers of births. Total births are near historic lows, while births to UK-born mothers are at a record low:

Around 70% of births were to mothers born in the UK, and 59% were to mothers who described themselves as white British.

Looked at in terms of total fertility rates, the number of children per woman has fallen for both those born in the UK, and also for women born elsewhere. Both are below what demographers call the “replacement rate” of about 2.1, which leads to a stable population.

Again, Births data shows how uneven the pattern of migration is around the country.

In 2022 in Greater London as a whole, two thirds of babies were born to families with one or more parents born outside the UK. In Copeland it was 6%.

In Greater London 47% of babies had both parents born outside the UK. In contrast, in Torridge in Devon it was just 1%.

Births data also give us a measure of integration. The table below looks at children born to mothers from various different countries, and shows what proportion had a father (a) from the UK, or (b) from the same place as the mother.

Where the mother was from the UK, 86% of fathers were also from the UK. For mothers born in North America or Australasia 59% and 65% had a father who was born in the UK. For mothers born in Africa, 12% had a father who was born in the UK and 76% had a father also from Africa. For mothers from India 7% had a father born in the UK and 89% a father born in India.

Conclusion

The future is already here – it's just not evenly distributed

- William Gibson

The country is going through massive changes, and the pace of change has accelerated in recent years. But the impact of migration and ethnic change have been felt very differently, depending on where you live and work, whether you are young or old, or whether you live in a richer place or a poorer one.

The world of Westminster often takes a long time to catch up with the facts on the ground. The risk of that is particularly high here: politicians, journalists, leaders in government and business are all more likely to live in affluent villages or unrepresentative affluent urban exclaves; more make a choice of school, whether that’s through working the state system or paying privately.

Sometimes the debate on migration seems to suggest we face a choice between the country staying as it is, or changing.

That’s a misconception: massive change is baked in for the coming decades, given the different demographics of different groups - even without the tendency for migration to beget more migration in a chain process.

More of the country will increasingly feel like our multi-ethnic inner cities do today. This is one reason I favour a cautious and more selective approach. The choice facing us is not between change and no change, but between a lot of change and a massive amount of change.

In the second part of this post I will come back to the divergent experiences and economic outcomes of different groups of people who have come to Britain. The differences are so huge it makes little sense to talk of a typical immigrant experience. But nor is there a single experience for people born here.

David Goodhart was onto something with his “somewheres” and “anywheres”. The experience of people with lots of resources and choices about where to live and work and send their children to school can be very different to that of someone who may have little choice where to live; and who may have seen unprecedented change all around them.

Subject matter aside, hat tip for all the analysis leg work done here. Nothing like a good graph or chart and yours are very informative.

brilliant and informative article - thank you.