Wednesday sees the second reading of the Schools Bill.

The Bill is a disaster.

Over the last 30 years, schools in England have been improved by the magic formula of freedom plus accountability.

Instead of politicians in Westminster trying (and failing) to improve schools through micro-management from the centre, we decided to let those who actually knew what they were doing - teachers and school leaders - do what worked.

Freedom meant that instead of having to jump to attention and waste time on the latest ministerial fad, they could get on and use their initiative to improve things for pupils.

On the other hand, there was no free for all. Where schools were failing, they were taken over by other people: be it as sponsored schools or by joining a new trust, so they got the support of a successful family of schools.

Accountability went hand in hand with parental choice. Parents could vote with their feet, creating a powerful force for improvement and innovation.

The improvement of England’s schools relative to the rest of the world shows just how powerful that formula freedom plus accountability can be.

Freedom works

The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests show how England’s schools have improved. And the contrast is all the more striking compared to Scotland and Wales, where politicians pursued exactly the kind of anti-reformist agenda that Bridget Phillipson is now pursuing in England.

Between 2009 and 2022 England went from 21st to 7th in the PISA league table on maths, while Wales went from 29th to 27th. England went from 19th to 9th for reading, while Wales stayed 28th. On science England went from 11th to 9th, while Wales slumped from 21st to 29th.

It was a similar story in Scotland, which held its ground on reading (from 12th to 9th) but collapsed from 15th to 25th on maths and from 11th to 26th on science.

Similar trends are visible on other international comparisons. For example, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) found that from 2011 - 2023 England’s rankings all maintained or improved:

Year 5 Science went from 15th to 5th.

Year 9 Science: 9th to 5th.

Year 5 Maths: 9th - 9th

Year 9 Maths: 10th to 6th

Sadly, no comparison with Scotland and Wales is possible, as their governments withdrew from the study after poor results in 2007. But English children were doing better than anywhere else in the western world:

In contrast, Labour-run Wales went in a different direction, rejecting academies, abolishing school league tables, pushing discredited methods and moving towards a hazy skills-based curriculum rather than a knowledge-intensive one. The results have been a disaster. A searing report by the IFS, titled “Major challenges for education in Wales” notes that:

“PISA scores declined by more in Wales than in most other countries in 2022, with scores declining by about 20 points. This brought scores in Wales to their lowest ever level, significantly below the average across OECD countries and significantly below those seen across the rest of the UK”

“Lower scores in Wales cannot be explained by higher levels of poverty. In PISA, disadvantaged children in England score about 30 points higher, on average, than disadvantaged children in Wales… Even more remarkably, the performance of disadvantaged children in England is either above or similar to the average for all children in Wales.”

Wrecking crew

But alas, not everyone in class was paying attention.

Instead, Labour want to pass a bill which strikes at both parts of the magic formula: attacking both freedom and accountability.

I have worked in politics for 25 years and it is one of the most dumb and tragic things I can remember. It’s an act of pure vandalism, abolishing academies in all but name.

Just before we get to the Bill, it is worth saying that it builds on various destructive changes the government have already made, including:

Abolishing the Academy Conversion Grant

Abolishing the Trust Capacity Fund

“Pausing” / cancelling the round of 44 new free schools announced by the last government with no plans for any more

Ending simple one-word Ofsted judgements and replacing them (at some point) with a complex scorecard

Abolishing the failure regime that turned failing schools into academies.

Now, on to the Bill…

***The Schools Bill***

When they initially arrived in government, Labour planned a low-key piece of legislation called simply the Children's Wellbeing Bill. Initial briefings suggested a bunch of innocuous reforms to children’s social care, including some reforms the last government had been planning, like a national register of children not in school.

But at some point the plan changed, and it became the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill. The “schools” section is a highly ideological, un-evidenced onslaught on school freedoms.

As we will see, Ministers are unable to answer basic questions about the effects of key elements of their own legislation. They literally don’t know what they are doing and in many cases don’t have a clear argument why they are doing it.

Let’s walk through it.

1) Teacher pay: the end of freedom and accountability

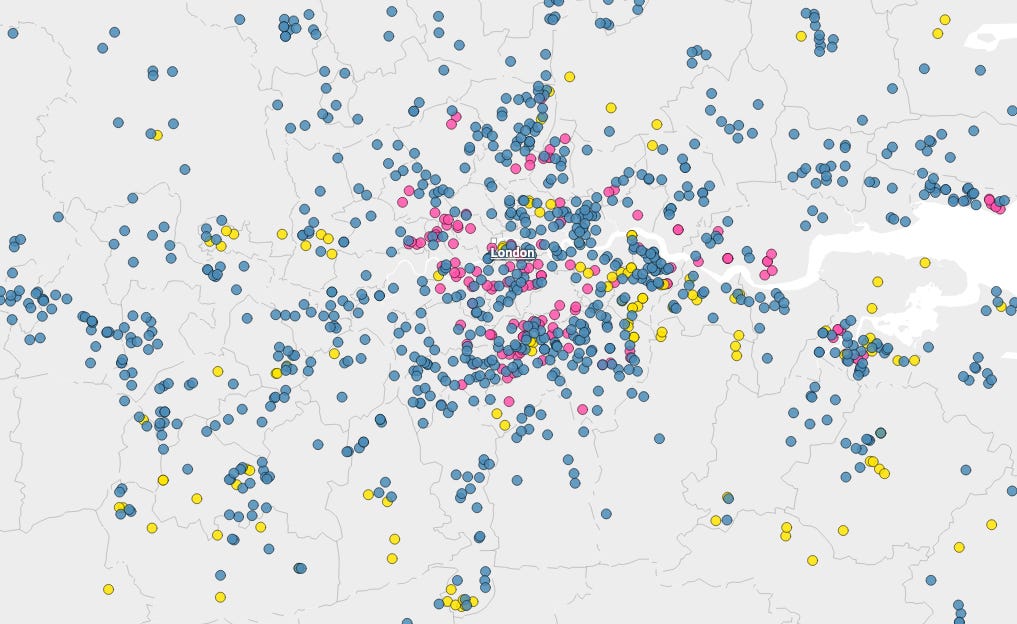

Section 45 of the Bill ends academy schools’ freedoms over pay. According to a brilliant study by the Times Education Supplement, 533 academy schools are using the freedoms they currently have to vary from national pay scales. Here’s how it looks in London for example: the pink and yellow dots are schools varying from the national scale.

This freedom to pay the best more helps to retain good teachers. For example:

The largest school trust in the country, United Learning, uses the freedoms to pay 5.6% above the figures set out in national pay and conditions by the government. They are keen to retain good teachers in their 90 schools, and their scale helps them make the back office savings they use to pay for it.

Dixons are giving teachers a nine-day fortnight - “As a trust, we have always tried to skew our budget towards teaching staff by reducing other costs, which has allowed for more PPA” (Planning, Preparation and Assessment time.)

Another very successful trust, ARK, pay approximately 2.5% above the national scale on each pay point this year.

The Schools Bill will take a steamroller to all this. Instead of paying more to hire and retain good teachers, the landscape will be squashed flat. Instead of your pay being linked to performance, schools will be back to national pay bargaining. The best and those who do more will get paid the same as the average; and sure as night follows day, more of the best teachers will leave the profession.

Ministers seem clueless about the effect of the legislation which they are themselves proposing. In an interview with the TES, Schools Minister Catherine McKinnell refused to say whether the new law would lead to pay cuts. Her exchange on the issue is truly extraordinary, so I reprint it here:

Asked whether she could guarantee that no teacher would have their pay cut as a result of the change, Ms McKinnell said: “No teacher should suffer detriment as a result of the changes, because we really want to retain good practice”.

Asked whether that was the same as saying there would be no pay cuts, she repeated that the Department for Education did not “think any teacher should suffer a detriment” and said it would “listen to the sector on this”.

TES put to her that there was concern that trusts currently offering above the national pay rate would have to reduce their offer, and asked if she could confirm that this definitely would not happen. She highlighted that the changes would not be brought in until September 2026 at the earliest, and said she was “keen to hear from academies”.

Asked whether she had an idea of how many academies or trusts deviate from the national pay offer at the moment, she said: “So that’s why we’re very keen to hear from the sector. Our understanding is the vast majority of schools do follow the national framework”.

So there you have it folks. Ministers don’t know how many teachers will be affected by their changes, can’t say it won’t mean pay cuts, and can’t even explain why they want to do this. And yet, they are still legislating.

As former DFE official and school trust leader Sir Jon Coles explains:

“The academy system [means] competitive pressure between employers which drives up pay for teachers… there is cost-protection for Treasury: budgets are fixed in the same way for all schools, without reference to pay, so there is a natural ceiling. We can only pay more to the extent that we can create efficiency in the back office… But of course union leaders and HMT (Tony Blair's 'forces of conservatism') hate the loss of personal control and attention in these more local pay negotiations - despite the fact that it's good for teachers and good for fully staffed public services.”

The government’s notes for the Bill display a kind of Orwellian doublethink:

“We recognise the good practice that academy trusts have developed over the years, but good practice shouldn’t be limited by administrative structures.”

If it is “good practice”, why isn’t the government extending this “good practice” to all schools rather than taking it away from academies?

As a final kicker, DFE have told Schools Week that the centralisation of pay will not apply to senior staff.

“senior executive leaders appointed by multi-academy trusts or single academy trusts are not within scope, even if they are also the principal or headteacher”

DFE are now trying to spin that this new law won’t change teachers’ pay. If not, why are they doing it? And if centralisation is so good, why doesn’t it apply to senior staff?

2) The curriculum: the end of freedom and accountability

Many academy schools use their freedoms over the curriculum to do something distinctive. Some vary from the national curriculum a little, others much more substantially.

Michaela School - where pupils saw the greatest progress in the country three years in a row, has an incredibly distinctive and knowledge intensive curriculum.

The curriculum developed by the ARK family of schools is so successful they have exported it - and it is now used by over 1,000 schools (see what can be achieved when you take the politicians out).

The freedom to vary from the national curriculum promotes genuine diversity in our schools. Not all children learn in the same way. Parents can choose what is right for their child.

It also protects schools from politicians. In Scotland the ironically named “Curriculum for Excellence” has been a big part of Scotland’s schools disaster.

As well as making the national curriculum compulsory, ministers are also overhauling it at the same time. Numerous groups are lobbying for various forms of indoctrination to be included.

Ministers’ motivation for this review seems to be to cut the time spent on core academic subjects to make room for creative arts. Now, if an individual school wants to do that, and can attract pupils, then fine. But I don’t think this should be imposed, and moree generally, having whoever happens to be DFE minister today able to impose their personal preferences on every school in the country is not a recipe for progress.

Many schools will now have to spend a lot of time not working out what they want kids to know, but instead churning through the new-look curriculum to work out if they comply. It’s another move back from a culture of teacher empowerment to a ring-binder-tick-box compliance culture.

Again, the government doesn’t seem to know how many schools will have to re-write their curriculum as a result, or be able to say why it thinks this will help, beyond their obsession with making everything the same.

There may also be an issue for some newly built schools which may lack facilities to follow the national curriculum - for example sufficient facilities for food technology or D&T. Again, we will have to see if ministers offer to meet the costs (spoiler: they won’t).

3) Ending academies’ discretion over QTS & making recruitment harder

Last month data came out showing the government had only recruited 62% of their target number of students into Initial Teacher Training for secondary schools, with particularly dramatic shortfalls in subjects like physics (just 30%), business studies, D&T, music, computing, and chemistry.

The NEU talks about a “global teacher recruitment and retention crisis” and school systems all across the world (with the possible exception of Singapore) are battling to try and recruit teachers.

We are rather insular in the UK, but if you simply google “teacher shortage Ireland” or “teacher shortage Australia” (or anywhere really) you will see what I mean.

Between 2011 and 2023 the last government added 29,454 extra teachers to schools in England and grew the total school workforce by 96,555 or 11%. But we still have a shortage of teachers in key subjects.

So this might seem like a very odd time to make things harder for schools to recruit and retain good teachers, but that’s exactly what clause 40 of the Bill does, repealing academy schools’ freedom over QTS status. At present if the head thinks that a teacher (perhaps from the independent sector, or an experienced teacher from overseas) is a good teacher they can employ them even if they don’t have Qualified Teacher Status.

There are about 13,600 teachers in this position. For context, that is twice the number of additional teachers (6,500) Labour have promised to recruit.

Lots of those who enter state education without QTS (about 600 a year) go on to get it - but the fact that they can join state schools without doing this up front reduces the barriers to entry, and makes it a bit easier to recruit into state schools.

The Treasury estimated that moving the existing stock of non-QTS teachers onto QTS would cost schools about £54-£127 million for the existing stock, and then £7-15m a year for the flow of new teachers entering the state sector via this route.

In local government there is a rule called the “New Burdens Doctrine” - if central government introduce any new policy or initiative which increases costs for local government, then central government has to pay up for it. Sadly for schools, no such thing applies here, and there is no sign ministers plan to compensate schools for this cost.

More fundamentally, where is the evidence that DFE know better who to employ than school leaders themselves? Sadly, this is just another example where Ministers believe “They Know Best”.

4) Stopping the academies revolution and moving back towards LA-run schools

Clause 44 of the bill repeals the requirement to turn failing LA schools into academies - in future this will be at the discretion of the Secretary of State. This requirement to find new management for failing schools has been at the very heart of the academies revolution.

Clause 51 of the Bill ends the rule that new schools are academies and allows Local Authorities to choose to set up new LA-run schools instead.

Both will undermine school improvement by reducing the flow of new schools into the best-performing trusts.

It will also create a mess. The schools system is still currently a halfway house. Over 80% of secondary schools are now academies, but less than half of primaries are. So just over half of state schools are academies. Most academies are in a trust: of the 11,224 open academies and free schools as of 1 December 2024, 10,352 are part of a multi-academy trust.

It would make sense to continue and finish the job: some local authorities find themselves running very small numbers of schools.

Instead, Bridget Phillipson has decided to roll backwards to a world where local councillors, rather than teachers, will be responsible for driving up standards.

5) A new power for the DFE to give orders to academies on any subject

Clause 43 of the Bill gives the Secretary of State a sweeping power to order academies about on any subject of her choosing, on any subject where she thinks the school:

“has acted or is proposing to act unreasonably with respect to the performance of a relevant duty”

This is another massive nail in the coffin of freedom and accountability.

The notes attached to the Bill give a chilling insight into just how micromanaging Phillipson intends to be:

The following are examples of the circumstances in which a direction might be issued:

• If the academy trust’s school uniform policy does not conform to the new school uniform requirements for a limit on branded school uniform items being introduced under this Bill, the Secretary of State would issue a direction requiring the academy trust to update and implement its policies in line with the legal obligations.

• The academy trust has failed to deal with a parental complaint and has not followed its complaints process.

If these are the kinds of examples the government are talking about now - that a parental complaint or the wrong kind of school jumper can trigger an intervention from the Secretary of State - then you can bet your bottom dollar this sweeping new power will be used in an even more micromanaging way in practice.

6) Chopping down the tall poppies: taking away the freedom of good schools to grow

The first major milestone in schools reform in England was the 1988 Education Act. It enabled good schools to expand, unshackling them from controls by their local authority. Labour built on it, as did the coalition government after that.

But parental choice has always been an idea with powerful enemies. One of the worst examples of Treasury short-termism (and I say this as a former HMT employee and fan) is an obsession with trying to eliminate competition and choice within the schools sector. Today the top of the progress league table is dominated by Free Schools: they are the type of school in which pupils make the most progress.

Yet the Treasury has always pushed against the Free School programme and the idea of new schools opening where there are “already enough places”.

Note that I don’t say enough “good” school places. HMT sees it as cheaper in the short term to force more parents into bottom-choice, struggling schools with a massive plunger, rather than to enable new schools to open or good schools to expand.

Because of the way these new entrants make other neighbouring schools raise their game, the anti-reform left has also been hostile to the creation of “surplus places”. This opposition to choice and dynamism is the same logic that made the Soviet Union such an economic success story.

But with the Schools Bill the anti-reform axis of the Treasury and the left are finally going to get their way:

Clause 47 creates a requirement for academies to cooperate on admissions and place planning, and gives the Secretary of State power to intervene if they don’t.

Clause 48 extends local authorities’ current powers to direct a maintained school to admit a child, to also enable them to direct academies in the same way, while Clause 49 widens the circumstances under which they can do this.

Clause 50 gives the schools adjudicator the power to set the published admission number (PAN) of a school, including academies, “giving the local authority greater influence over the PANs of schools in their area”

This last is particularly important. As the notes to the bill explain:

“At present, objections to PANs can only be made where an admission authority has decreased a school’s PAN. We intend to amend the 2012 School Admissions Regulations to extend local authorities’ ability to object to the Adjudicator, to enable them to also object where a school’s PAN has been increased or has been kept the same.”

In other words, this will make it harder for good schools to expand, and will give local authorities the ability to challenge even a decision to keep numbers the same.

This could be a particularly big deal, because we’re just about to enter a new era of falling pupil numbers after years of growth. Nationally the number of pupils in state-funded nursery & primary schools is set to fall 4.5% from 2024 to 2028 alone. But within that there are a large number of LAs forecasting a local decline of over 10% - particularly in London and other urban areas.

It will be tempting for bad local authorities to prop up unpopular schools (particularly LA-run ones) by “sharing out” the pupils from more successful schools, and preventing the growth of good schools. This is another giant step away from the logic of freedom and accountability that drove up standards.

7) Micromanagement on steroids: even school uniform will be run from Whitehall

When I was a school governor (mainly under the last Labour government) I was struck by the flood of paper that issued forth each week from the DFE. The flood abated a bit after 2010.

But that may soon seem like a golden age, as it seems like under new ministers the politician’s urge to micromanage schools is going to go into overdrive.

Parents are spending less in real terms on school uniforms than they were a decade ago. A poll by the DFE found that average total expenditure on school uniform last academic year was £249.58, compared with £279.51 for a similar period in 2014-15 after adjusting for inflation. Guidance introduced in 2021 encourages schools to have multiple suppliers and hold down costs.

And yet the government is now planning to take complex primary legislation to micromanage exactly how many items of uniform can be branded or specific. It will be the law of the land that a school:

a) may not require a primary pupil at the school to have more than three different branded items of school uniform for use during a school year; (b) may not require a secondary pupil at the school to have more than three different branded items of school uniform for use during a school year (or more than four different branded items of school uniform if one of those items is a tie)….

What counts as “branded?” In the same way lawyers spent years arguing over whether a Jaffa Cake is a biscuit or not, schools (and courts?) will have years of trying to work out this sentence:

An item of school uniform is “branded” if (a) it has the school name or school logo (or for an Academy, the school or proprietor’s name or logo) on or attached to it, or (b) as a result of its colour, design, fabric or other distinctive characteristic, it is only available from particular suppliers.

So despite falling costs, very large numbers of schools will now be spending time on rejigging their uniform policy rather than anything else.

How many? As with reforms on pay and curriculum, the government is legislating without knowing. On this definition the average secondary school has 5.2 branded items at the moment so almost all secondary schools will have to review their uniform.

Costs for parents may well increase: many schools will go stop having PE kit as uniform, at which point (highly brand-aware) kids will push parents to have stuff from Nike or Adidas (or whatever kids are into these days). Lots of primary schools (including our own kids) have jumper, tie, PE top and plastic book bag. If they stop the last of these then any other bag will be likely more expensive (and thankfully our kids are too small to want expensive brands). It’s unclear what will happen with school sports teams - I think DFE hope schools will buy kit for teams.

Given the big real-world challenges of attendance, teacher retention and behaviour, this would not be my priority for how school leaders spend their time. Indeed, if ministers wanted to cut costs they could take VAT off school uniform: weirdly uniform for over 14s gets taxed. But they won’t do that.

Instead, we have this bill, marking an unwelcome return to an era in which ministers think they can run everything with central micromanagement. When you start having Whitehall managing ties and school jumpers, you know a new era of red tape and meddling is coming.

Conclusion

England’s schools are an unusual thing in politics: an area where there was significant cross-party agreement, where successive generations of ministers drove through structural reforms which worked. We can see that alternative strategies pursued in Wales and Scotland had just the opposite effect.

If the government were just drifting, that would be bad enough - we should be doubling down, helping the best trusts to grow.

But it’s worse than that. The Schools Bill is an onslaught on the combination of freedom and accountability that has driven improvement.

Ending freedom over teacher pay and the curriculum

Ending freedom over QTS and making recruitment harder

Taking sweeping powers to give orders to academies on any subject

Taking away the freedom of good schools to grow

Stopping the academies revolution and moving back towards LA-run schools

Bringing back micromanagement

There are real challenges we should be focussing on - recruitment, discipline, attendance. But instead we have this Bill, with its retro priorities.

I remember what schools were like in the 1980s and 90s. It was chaotic, with kids getting dangled over high stairwells and loads of fights. Hopeless methods meant loads of people in my class couldn’t read well, even by GCSE year. Decent teachers seemed ground down. We flushed away the life chances of a lot of people I knew.

Schools today are generally much better. But that isn’t an accident: it’s the result of reform.

But the world is getting more competitive: we need to keep going. Instead we are turning back.

Honestly, it breaks my heart.

Great post Neil. I think people don't appreciate how much we - and Nick Gibb especially - had to constantly defend against this in government.

This is powerful. It’s also deeply depressing. Well done for raising the alarm, I hope resistance might develop. What is it about Phillipson? She is the enemy of achievement.