One of the first things the new Labour government did was to revise housing targets for local authorities.

One of the peculiar things about the change to the formula was that they reduced housing targets for London and other cities. The map below shows how the old target compares to the new target for each local authority1.

Greater London goes from being asked to deliver 98,822 dwellings a year to 80,693 - down 18%.

London’s numbers are cut even as the rest of England goes from 206,000 to 291,000 - up 41%.

The same reduction seen in London applies in other cities to a varying extent. Newcastle’s target is down 5%, Bradford’s 6%, Bristol 9%, Southampton and Sheffield 12%, Nottingham 21%, Luton 22%, Birmingham and Leicester are down 31%, and Coventry down a whopping 50%. Of these Birmingham is particularly significant as it is the biggest planning authority in the country.

In contrast, non-urban areas outside London see big increases. The North East is the region with the greatest increase - its target is doubled from 6,123 to 12,202. The North West is a close second, with a three-quarters increase. And that’s including the cities with the reductions - without Newcastle the rest of the North East is more than doubled - up 130%.

On the face of it, this seems like a very strange thing to do, given that house prices are so much higher in London than the urban North East. The average house in Camden is six times the price of one in County Durham.

It’s not just that prices are high in absolute terms. They are high even relative to income. The median private renter in Yorkshire spent 23% of their income on rent, but the average Londoner 35%.

In London, housing costs are responsible for pushing 11% of people below the government’s preferred poverty line, compared to 5% in the UK as a whole.

London is also the place where the polls show most people are concerned about housing: The most recent MORI issue tracker showed Londoners were twice as likely as others to say housing is the top issue facing the country.

And there are a variety of environmental reasons why you might think a net zero-obsessed government would want to do more in our cities: energy use and emissions are lower in cities because of denser housing (which use less heat) and lower usage of car transport.

The numbers are big. In cities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Nottingham and Leicester, the household emissions are 15% lower than the national average. The transport emissions are 35% lower—there is more walking, more cycling and more public transport. Ed Miliband would normally kill for those kind of carbon savings.

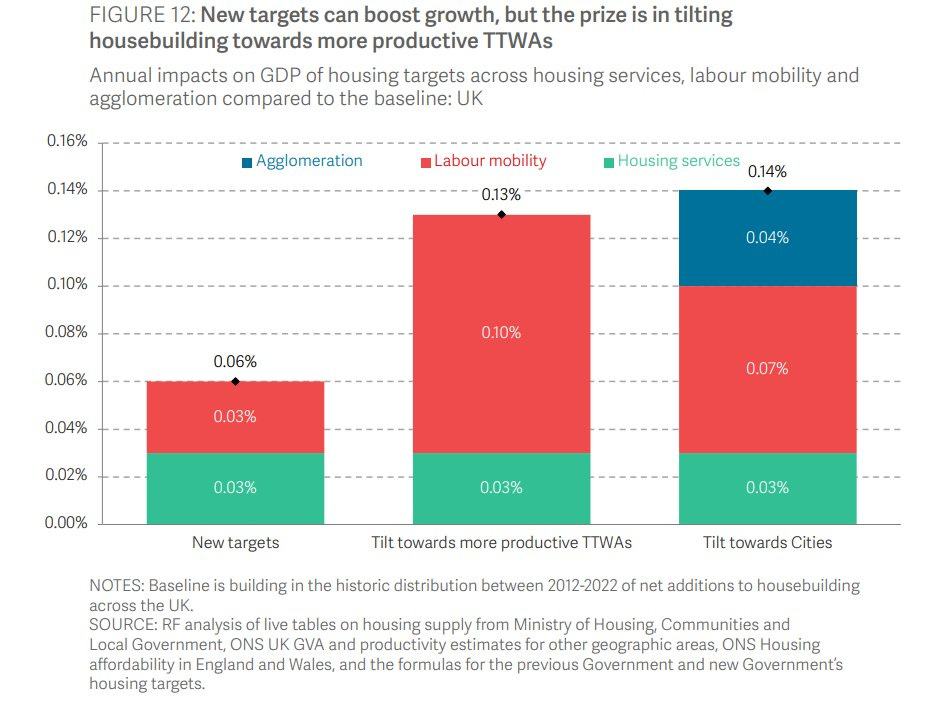

Even the centre-left Resolution Foundation have been critical of the new targets - arguing that a shift towards cities would be better for agglomeration gains and economic growth:

They note that:

“if the Government wanted to prioritise growth, it could reconsider its housing targets, shifting construction towards more productive areas, or towards cities. Our estimates suggest that tilting building towards more productive areas would boost GDP growth by a total of 0.13 percentage points each year. Alternatively, prioritising cities to take advantage of the agglomeration effects would boost GDP growth by 0.14 percentage points each year.”

The anti-urban shift is also surprising given that London has seen the greatest gap between population growth and housing growth over recent decades.

The data starts in 2001, and over the period 2001-2023, London built 43 extra dwellings for every 100 extra people, while the rest of England built 58 extra dwellings for every 100 extra people.

It’s the same for other cities - our cities are the places where housebuilding has lagged most dramatically behind population growth, so stand out as red dots in the map below.

Closing this urban housing gap was the reason the previous formula contained an uplift for urban areas. Taking that out (wrongly in my view) is part of the reason why the target numbers have swung down for cities, but up for the rest.

But that is only part of the story.

As noted above, the effect of new formula varies massively, even between cities.

The Consultation explains how the new formula works, and say that it

a. uses a baseline set at a percentage of existing housing stock levels, designed to provide a stable baseline that drives a level of delivery proportionate to the existing size of settlements, rebalancing the national distribution to better reflect the growth ambitions across the Midlands and North;

b. tops up this baseline by focusing on those areas that are facing the greatest affordability pressures, using a stronger affordability multiplier to increase this baseline in proportion to price pressures;

The government claims it is “increasing the significance of affordability” in the calculations.

So how on earth can the numbers be going down in London, when it has the most expensive housing in the country?

The first part of the explanation is the shift to a formula based on a share of the existing stock, rather than population forecasts. In relative terms this pulls the numbers down in London and the South West and West Midlands. It increases them a bit in the South East, and a lot in in the North.

The increase is particularly dramatic in the North East, which has the slowest population growth, and contains various places where the population has declined. This means the stock of existing housing there is much greater relative to the population forecast.

The effect of shifting off population forecasts and onto share of existing stock is then either counteracted - or amplified - by the revised affordability element.

But the new formula uses a very particular measure of affordability, which I have criticised when it was used in previous formulas. This measure is:

Non-mix-adjusted. The measure being used is not trying to tell you how much a similar property would cost you in different areas. Instead, if there are more 1-bed flats being sold in place A and more 3-bed houses in place B, then on this measure place A is cheaper - even if a 2-bed house costs exactly the same in both.

Workplace-based. It is based on the ratio of the house price in an area to the income of the people who work in that area, not those who actually live in that area. So if a place has a lot of commuters who go off work somewhere else to earn more than the average where they live, then where they live looks less affordable, and the place they commute to looks more affordable. Wherever there is commuting, this becomes quite a peculiar measure: it tells you how the price of a house in an area compares to the incomes of people who don’t live there.

Overall, though there’s variation, both these choices push in the same direction when it comes to cities.

They make house prices look lower in our cities (where housing is denser)

They make earnings look higher in our cities (where people commute in to)

Let’s map both. Here’s the impact of the decision to use a non-mix-adjusted measure compared to the mix-adjusted measure used in the official ONS House Price Index.

Homes in London look 5-10% cheaper on the non-mix adjusted measure, while most of the rest of England looks more expensive2 - this includes other cities because London is so much denser.

Now lets look at the use of workplace-based stats.

Using workplace-based affordability measures has some very curious effects. Did you know that it is more affordable to live in the glamorous City of London than in gritty Brent or Barnet or Haringey?

Well, obviously it isn’t in the real world, but according to the government’s preferred measure it is, because the bankers who commute into the square mile are have super-high earnings, even relative to the super-expensive housing there.

On the government’s measure, fancy Islington is more affordable than a commuter-belt town like Sevenoaks. But for the people who actually live in these places, it’s the other way round. Our cities pop out in blue on the map below because of the choice of measure the government is using.

The combined effect of these measures is to end up with a target which is more demanding relative to future population forecasts in the North East than it is in London.

We should really take a much broader view of housing costs.

The use of a) earnings and b) sale prices means this measure is only a subset of the overall question of overall housing affordability. Many people (particularly in urban areas) rent not own. And many aren’t earning anything, because they are not working or are pensioners (and there’s lots more pensioners outside our cities).

The government could use total housing costs as a share of total income, or even look at what people have left over after housing costs, as suggested by Geoff Meen here.

An all-in measure of housing costs takes into account private renters and social renters as well as owners, includes the shares of each, and the total income of everyone, not just their earnings. Here’s a calculation from the IFS. During my lifetime London has become radically more expensive than the rest of the country.

The only good objection to using an all-in measure like the one above is that it is based on survey data, so potentially not granular enough to use for every local authority. But we can find other measures which proxy it and are very granular.

For example, one of the simplest ways to measure the housing problem is just overcrowding3 - which is driven by total housing costs and total income.

Overcrowding is almost entirely an urban phenomenon, which makes cutting the taret numbers in our cities all the more surprising.

Here’s overcrowding from the Census. London, Birmingham, and the cities of the urban north and midlands all pop out immediately.

On the government’s measure, houses in Derby are twice as affordable as those in the Derbyshire Dales. So how come there’s five times more overcrowding in Derby?

Here’s affordability on the government’s measure. It can “see” that the south is more expensive than the north - but it can’t see the factors causing London and other cities to have so much more overcrowding than their surroundings.

Real-world measures like overcrowding capture things which the official stats on price-to-earnings ratios don’t.

Conclusion

In the end, there is no “objective” measure of how much we should build in each place. You need a vision of what you want the country to be like. You can place whatever weight you want on different measures of need or demand; on different kinds of environmental, social and economic impacts; on different measures of welfare and feasibility.

The government has chosen a measure which shifts the growth out of our cities, and particularly out of London. I’d argue that:

we already have the least dense cities in Europe by a long way,

the choice for non-urban areas contradicts the governments green goals,

the definition of affordability they are using is at best incomplete and has some perverse effects,

overcrowding is a hard measure which shows you the housing problem is most intense in our cities.

It is true that development in urban areas brings challenges. Britain’s volume housebuilders much prefer greenfield development - not least because it creates great opportunities for them to generate profits by gaming the current planning system.

These reasons were why we: set up MCAs; increased funding for the regeneration arm of Homes England; and passed the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act last year - which, amongst other things, makes CPO powers stronger and easier to use.

We do indeed need to build more houses. There are also many other things we need to do to make housing more affordable, but supply absolutely does matter in the long run.

But the effect of what Labour have done is odd. On paper the new targets are much higher. But they are much lower in the places where the housing crisis actually is. They have swung a big hammer, but somehow missed the nut.

I have had to consider Dorset and BCP as one entity and give the average because of the interaction of overlapping plans and local government reorganisation.

In an ideal world you would use some sort of measure of affordability per square foot.

A Conservative Member of Parliament said sometime last century:

'If one party has a housing target - though who ever heard of a clothing target, or a food target, or a car target, or a television set or foreign holiday target? – then the other party is expected to have a housing target too, and a bigger one if possible. So we are all of us habituated to government interference, to the point when we can hardly imagine life without it.'