The flawed analysis behind the ban on short prison sentences

From bad analysis to a bad policy

On Wednesday we will have the second reading of the Sentencing Bill. Section 6 of the bill bans the courts from giving people prison sentences of less than a year, except in exceptional circumstances. Section 6 (2) says they will get a suspended sentence instead.

The court must make a suspended sentence order in relation to the sentence where this section applies unless the court is of the opinion that there are exceptional circumstances which— 35(a) relate to the offence (or the combination of the offence and one or more offences associated with it) or the offender, and (b) justify not making the order.

This ban has been a long cherished goal of anti prison campaigners. It is being done now because the MOJ fears we are about to run out of prison capacity, which is itself partly as a result of welcome moves to end early release at the halfway point and jail rapists for longer.

But MOJ officials and anti-prison campaigners have long argued that community sentences are “better at reducing reoffending than short prison sentences”. A recent analysis MOJ they published on this issue is here.

This is the basis of the claim that people given prison sentences of less than a year are 4% more likely to reoffend:

The one year reoffending rate following short term custodial sentences of less than 12 months was higher than if a court order had instead been given (by 4 percentage points),

But the analysis is fatally flawed. It is comparing reoffending from the start of a community sentence to reoffending from the end of a prison sentence - so totally ignoring the effect of the actual time in prison on reoffending!

In fairness, the authors of the report point this out (my bold):

Comparisons of custodial sentences with community sentences are therefore ‘like for like’ in that the follow-up period for both is of the same length and takes place while the offenders are in the community. However, this obscures that for custodial sentences, the follow-up period begins after time spent in custody during which the offender has much reduced risk of reoffending.

Prison has three effects: it directly incapacitates prisoners; deters offending and can rehabilitate and changes offenders’ behaviour. Although anti-prison activists hate hearing this, the first and second of these effects are important for public safety, and the MOJ analysis also ignores them.

Why this is a mistake

There are two main reasons I think the ban on short prison sentences is a mistake.

First, I think that justice sometimes requires such sentences, and that it is wrong to fetter the discretion of the courts to given them out except in exceptional circumstances.

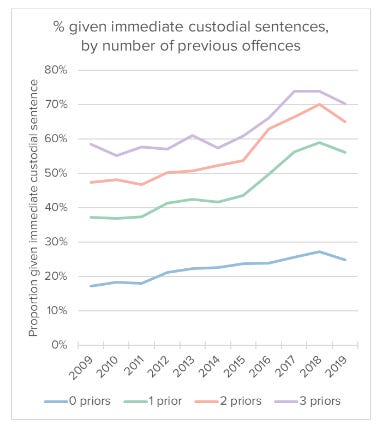

Second, there are a large cohort of prolific offenders for whom endless community sentences and endless suspended sentences simply do not work. I wrote an analysis of this a while back.

Roughly half of all crimes are now being committed by 10% of offenders, and 4% of all crimes are being caused by 0.2% of all criminals.

Between 2007 and 2018 the number of super-prolific criminals, (offenders with more than 50 previous convictions) who were convicted but spared jail tripled, from 1,299 in 2007 to 3,916 in 2018. Over a decade there were:

206,000 offenders who were convicted but did not receive an immediate custodial sentence, despite having more than 25 previous convictions.

32,000 offenders who were spared jail, despite having more than 50 previous convictions and;

2,450 offenders spared jail, despite having over 100 previous convictions.

Offenders placed on community sentences between 2007 and 2015 were convicted of over 1.2 million crimes, including 46,675 offences of violence against the person and 472,000 thefts.

You have to really be a wrong ‘un to go to prison these days.

Of those who were subsequently jailed, the number who had previously received 10 or more community sentences increased from 3,853 in 2007 to 6,216 in 2018.

The proportion of those jailed who had five or more previous community sentences increased from around a quarter (26%) to nearly a third (32%) over the same period. Only 27% of those jailed in 2018 had no previous community sentences.

In more recent years community sentences have increasingly been displaced by suspended sentences. Of those jailed, the number with five or more previous suspended sentences increased nearly tenfold, from 286 to 2,735 over the same period. The Sentencing Bill will take use further in that direction.

In the 2019 leadership campaign Boris Johnson referenced my research above and the 2020 Sentencing White Paper also references the issue. I want us to move more quickly to start dealing with the super prolific offenders who cause so much crime. More suspended sentences isn’t the way to do that.

Discretion advised

One irony in this debate is that some of the supporters of banning short sentences are the same people who argue strongly against fettering of judicial discretion whenever proposals are advanced for more automaticity of sentencing.

For example, the courts have largely ignored Parliament on repeat knife offenders. Under Section 28 of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act, which came into force in July 2015, adults convicted for a second time or more of carrying a knife must receive a minimum six month prison sentence. But to avoid a judicial backlash, a clause was inserted saying this applies unless there are “particular circumstances” which “would make it unjust to do so.”

The courts find it ‘unjust’ an awful lot. While the proportion of those convicted of a repeat offence of carrying a knife increased, it is far from 100%, even for those with multiple offences. In 2019, 35% of over 16s for whom it was their third conviction for the same offence were not jailed, while 30% of those for whom it was their fourth or more offence of knife possession were not jailed.

It is similar on burglary: In the 1997 Police Bill the then Conservative government attempted to set various mandatory sentences for repeat offenders: “three strikes and you are out.”

But a series of amendments in the Lords undermined the intent of the legislation. The argument was that we mustn’t fetter judicial discretion. The result is that, of those who were convicted for the third time of burglary, 14% were not even jailed in 2018.

Conclusion

I feel for Alex Chalk - a brilliant minister who has inherited this problem, and who clearly believes he has no alternative but to pursue this policy or have prisons overflow.

But I think we should have a loop around again and look at whether there is any possible alternative here.

Full disclosure: I must include a declaration of interests here. I have one prison in the middle of my constituency (HMT Gartree, all lifers) and another one on the edge (HMP Fosse Way, Cat C). The government recently overruled my local council and also the planning inspector to build a further large prison. I have supported my local council and local residents campaigning against it who argue this is the wrong place. I am absolutely not against new prisons: in fact I am in favour, and have told MOJ on several occasions they would have had their new prison open by now if they had gone to a site which didn't provoke such local opposition. No doubt some will think me a hypocrite for this, but my constituents say that if we are to have the extra prison here, they would at least like to see the benefit in terms of stronger sentences.