Sex education in schools: part two

Schools are trying to navigate a minefield, but the government it sitting on its hands - with bad consequences for kids

The first part of this post looked at how sex education in our schools has gone wrong. This second part looks at why and how this happened.

Let’s start with recent developments, then we’ll rewind a bit further.

In December 2023, the Department for Education published a consultation on draft non-statutory guidance for schools and colleges in England on children questioning their gender. The consultation was open until 12 March 2024.

Then Minister for Women and Equalities, Kemi Badenoch said:

This guidance is intended to give teachers and school leaders greater confidence when dealing with an issue that has been hijacked by activists misrepresenting the law.

Yet here we are in summer 2025, and it still hasn’t been issued. New Secretary of State Bridget Phillipson is still “thinking about” the guidance.

Likewise, in the summer of 2023 Rishi Sunak answered a call from Miriam Cates for an urgent review following reports of inappropriate sex education lessons, resulting in the government publishing a draft statutory guidance in May 2024 and opening a consultation on RHSE - Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education.

That closed in July last year, but nearly a year later, nothing has been published. Again, the new government is “thinking”.

But while the government ponders endlessly, schools are trying to navigate their way through a minefield of difficult issues every single day.

What was the last government trying, belatedly, to fix? And why is the new government finding it so hard to make up its mind?

The basic problems are these:

There is little or no consensus on what should be taught at what age, and in many cases what is taught is a long way out of line with what many parents would want.

Provision of lesson plans and materials has increasingly come from unregulated third parties, often radical campaign groups, leading to safeguarding failures.

These groups abuse copyright law and their subscription models to block parents and others from circulating or discussing their materials. This prevents parents from discussing legitimate complaints, and blocks both democratic discussion and proper regulatory oversight.

How did we get here?

How we got here: 1945-2019

For most of the postwar period education about sex and relationships was regarded as first and foremost a matter for parents. For most of the postwar period Britain was a relatively homogenous country with a greater level of consensus about moral and social issues than it has now.

For example, as part of the state takeover of schools after the war, it was agreed that all pupils in state schools in England and Wales must take part in a daily act of Collective Worship, “of a broadly Christian character” unless they have been explicitly withdrawn by their parents - indeed, this is notionally still a requirement.

Though the Board of Education conducted a survey of what schools were teaching about sex in 1943, schools were generally left to their own devices. The Department of Health were keener than the Department for Education on the idea of sex education, which they hoped would reduce sexually transmitted diseases. But both the teaching unions and the DFE were wary of centrally dictated sex education, so the department confined itself to issuing various forms of fairly uncontroversial guidance, like “School and the Future Parent.”

Sex education rolled out in schools in stages. The 1986 Education Act specified that where there was sex education it should promote moral values and family life, and that each school and LA should have a published policy on whether they offered sex education, and the contents of it.

It was the 1993 Act that first made sex education compulsory - in two ways. First, the basic biology of reproduction became part of the national curriculum for science. Second, all secondary schools were required to offer sex education. It says something about the health-driven motives for this move that the one specific requirement to be mandated was that sex education should include information on AIDS and STIs. Though provision of sex education was made compulsory attendance was not: the trade off was that parents were given the right to withdraw their children from these lessons. This was regarded as an important way to maintain the principle that parents not the state should be able to decide how their own children are taught about these issues.

Sex education was highly focussed on factual, biological information relating to procreation, contraception and the avoidance of sexually transmitted infections. In so far as there was an ethical framework coming with it, it was a consensus-maximising, small-c conservative agenda. Accompanying the new law, the 1994 guidance stated:

The purpose of sex education should be to provide knowledge about loving relationships, the nature of sexuality and the processes of human reproduction… It must not be value-free; it should also be tailored not only to the age but also to the understanding of pupils.

Pupils should accordingly be encouraged to appreciate the value of stable family life, marriage and the responsibilities of parenthood. They should be helped to consider the importance of self-restraint, dignity, respect for themselves and others, acceptance of responsibility, sensitivity towards the needs and views of others, loyalty and fidelity. And they should be enabled to recognise the physical, emotional and moral implications, and risks, of certain types of behaviour, and to accept that both sexes must behave responsibly in sexual matters.”

Updated guidance in 2000 showed some significant shifts but also a lot of continuity in the Blair era - the carefully-negotiated paragraphs below give a flavour:

As part of sex and relationship education, pupils should be taught about the nature and importance of marriage for family life and bringing up children. But the Government recognises – as in the Home Office, Ministerial Group on the Family consultation document “Supporting Families”- that there are strong and mutually supportive relationships outside marriage. Therefore pupils should learn the significance of marriage and stable relationships as key building blocks of community and society. Care needs to be taken to ensure that there is no stigmatisation of children based on their home circumstances. […]

What is sex and relationship education? It is lifelong learning about physical, moral and emotional development. It is about the understanding of the importance of marriage for family life, stable and loving relationships, respect, love and care. It is also about the teaching of sex, sexuality, and sexual health. It is not about the promotion of sexual orientation or sexual activity – this would be inappropriate teaching.

So on the one hand no stigmatisation, but on the other, an ongoing emphasis on “stable and loving relationships.” The Learning And Skills Act 2000 reaffirmed similar points in law:

The Secretary of State must issue guidance designed to secure that when sex education is given to registered pupils at maintained schools—

(a) they learn the nature of marriage and its importance for family life and the bringing up of children, and

(b) they are protected from teaching and materials which are inappropriate having regard to the age and the religious and cultural background of the pupils concerned.

In the years that followed there was a lot of lobbying from activist groups for compulsory sex education and more ‘progressive’ content. A big milestone moment of change came in 2014 with the publication of “SRE for the 21st Century - Supplementary Advice”

First, the content of it was a major shift from the guidance of 2000, with multiple references to the contentious concept of “gender identity”, encouragement to teach about pornography, sexting, and a heavy emphasis on children’s rights and inclusion. It also heavily emphasised for the first time the inclusion of transgender issues:

Teachers should never assume that all intimate relationships are between opposite sexes. All sexual health information should be inclusive and should include LGBT people in case studies, scenarios and role-plays. {…}

Schools have a clear duty under the Equality Act 2010 to ensure that teaching is accessible to all children and young people, including those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT).

But as important as the context was the process. This new non statutory guidance was issued, not by DFE, but by a consortium of third party groups with the support of the DFE: “The Supplementary Advice is supported by the DFE and a range of other government, education and voluntary sector stakeholders.”

Despite not being a government document, there were supportive quotes from coalition ministers at the start of the guidance. The guidance also encouraged the use of materials and people from third party groups.

This shift to a kind of arms-length / third-party model of “soft governance” is hardly unique - there are many such examples, from the row over the Sentencing Council’s two tier sentencing plans to Natural England’s contentious interpretation of ‘nutrient neutrality’.

But in sex education - where there is so little consensus - this shift has been particularly consequential, and opened the door to very radical trans activists. None of this should be read as a criticism of policy makers at the time: it was extremely well intentioned, but happened to be followed immediately by the period in which trans activism suddenly became much more radical and the issues much more contested.

The Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education and Health Education Regulations 2019, (under the Children and Social Work Act 2017) made Relationships Education (not sex) compulsory for all pupils in primary schools.

The 2019 Statutory Guidance that went with this change represented another step change. It incorporated and deepened the references to the more contentious ideas in the 2014 “Supplementary advice”, with multiple references to gender identity.

It states that, “we expect all pupils to have been taught LGBT content at a timely point”, but doesn’t explain further. While it was relationships rather than sex education that was made compulsory in regulation the guidance states that, “The Department continues to recommend therefore that all primary schools should have a sex education programme tailored to the age and the physical and emotional maturity of the pupils.” [my italics]

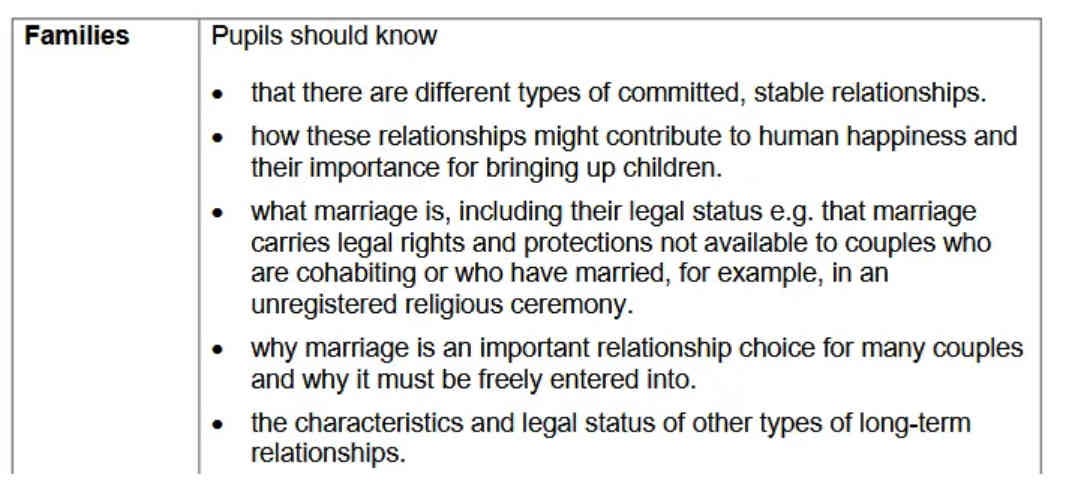

While the Blair era 2000 guidance had stressed the importance of marriage - “pupils should learn the significance of marriage and stable relationships as key building blocks of community and society” - the 2019 guidance takes a completely neutral approach:

Schools have been told there are many highly contentious subjects they should cover. But in contrast to many other subjects, the specification of what is to be taught is very vague. Contrast the statement that schools should “teach their pupils about LGBT” with the following physics specification for example. In physics, regarding diffraction, you will need to know the:

“Appearance of the diffraction pattern from a single slit using monochromatic and white light. Qualitative treatment of the variation of the width of the central diffraction maximum with wavelength and slit width.

-The graph of intensity against angular separation is not required.

Plane transmission diffraction grating at normal incidence.

Derivation of dsinθ = nλ

-Use of the spectrometer will not be tested.”

In contrast, in RHSE / RSE there is a lack of a clear specification of what is to be taught from the centre. Unluckily, the one thing that is quite specific - the reference to “gender identity” - has become a way in for activists to teach all kinds of extreme things.

So to summarise:

The 2014/2019 guidance encouraged schools to teach about contentious things, but with little specificity about what should be taught - except that the controversial idea of “gender identity” must be included.

This and the arms length creation of the 2014 guidance sent schools running to third party providers.

Unluckily, it turned out that this was done just the moment when we transitioned from a relatively calm period of sex and gender discussion to a period of trans activism (the so called ‘great awokening’)

We moved quite rapidly from guidance saying sex education must not be value free to guidance that was quite value free on paper….

…And the practical effect of this has been to allow radical groups to impose their own fairly extreme values

The steadily-percolating effects of the 2010 Equality Act (supported by same groups and forces) also created something of a feedback loop, as it was used by activist groups to browbeat schools into feeling they had to go along with their agenda.

These problems, which I will discuss below, are why in 2023/2024 the Conservative government produced the guidance on gender questioning children and the new draft RSHE guidance which, as I mentioned at the start, went out to public consultation.

The proposed new guidance was clear that: “Schools should not teach about the broader concept of gender identity. Gender identity is a highly contested and complex subject… If asked about the topic of gender identity, schools should teach the facts about biological sex and not use any materials that present contested views as fact, including the view that gender is a spectrum.”

This would have been a good start towards unwinding the issues that have emerged. But, as noted above, the current government is sitting on this guidance, and so the wild west continues. Let’s turn to that now.

From secret garden to wild west

“In any society where government does not express or represent the moral community of the citizens, but is instead a set of institutional arrangements for imposing a bureaucratized unity on a society which lacks genuine moral consensus, the nature of political obligation becomes systematically unclear.”

― Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue

Recent years have seen a dramatic shift towards the provision of contentious material in schools. The providers range from external campaign groups, through small, activist, one-man-band types of operations, right through to large ‘edutech’ companies.

The changes in sex education have been dramatic - though parents can’t easily see what’s going on because at present, sex education in schools is a secret garden.

Astonishingly, parents have no stated right in law to see what their kids are being taught. The private providers and activist groups who now provide much sex education and lesson materials hide behind copyright and commercial secrecy claims to prevent parental access.

Many also use online subscription charging models which are used to prevent parents and others from seeing, circulating and discussing their materials.

London mum Clare Page was denied the right to see the materials at her school, and has waged a long battle to fix this since. And yet, when we recently attempted to amend the Schools Bill to give parents a right to see what their kids are being taught and end secret lessons, Labour voted it down. One Labour MP argued that parents might be angry if they saw it. That is rather the point.

What is to be done?

The underlying problem is this.

On the one hand, there is now a dramatic lack of consensus about what should be taught or not taught. Indeed, in an increasingly hyperdiverse society, the zone of consensus is if anything shrinking: it surprises some people to learn that Londoners have the least liberal attitudes to sexuality (because of the capital’s ethnic mix). On the other hand, you there is a progressive monoculture among providers. Some are more extreme than others, but there is a monopoly of basic view.

One response to this is to argue that parents with concerns are simply wrong and should be overruled. I don’t agree with this fundamentally illiberal view - I think reasonable people can have justified concerns about what is being taught in many schools. Why?

Gender ideology has real world consequences and leads children down a bad route. At present schools are promoting it, praising it, giving it attention and status. As the Cass Review pointed out) it can be hard to get off an affirmation pathway. Gender dysphoria was not a thing in schools in the 1990s. It is a problem that has been (and is being) created for kids by a mix of irresponsible and well meaning adults.

The ideology being pushed relies entirely on gender stereotypes to an almost metaphysical extent - the way ideas like “girl brains” and “boy brains” are deployed are anti-scientific garbage.

It medicalises the normal struggles and confusions of childhood, and normalises ideas that are unhelpful ("trapped in the wrong body" / you were mistakenly ‘assigned’ at birth / you like cars so you are ‘really’ a boy).

‘Sex positive’ sex education is a politically partisan view that does not cater for the differing values amongst parents

I think we need to end the wild west, and end secret lessons. The guidance and approach needs a big reboot. What does that mean in detail?

As a first step, the two pieces of guidance the government is sat on need to come out without the key changes being watered down. We then need much clearer regulation of what is taught, and to rethink the idea of sex education in primary schools fundamentally.

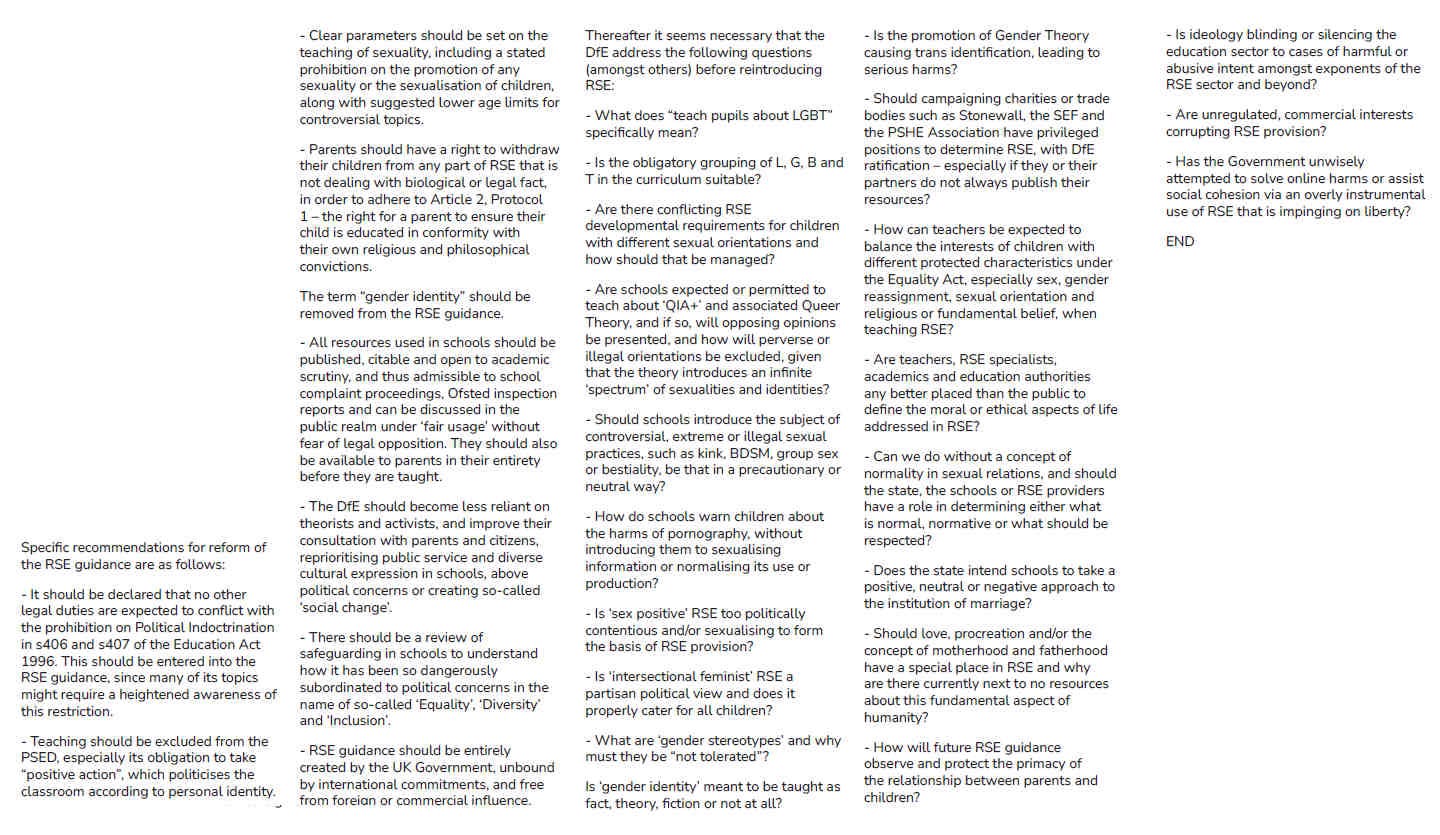

You could write a whole report on how to reboot things, but I think the list of questions and ideas produced in a report by the NSCU is an interesting place to start.

Most RHSE lessons are not taught by specialists but by form teachers - and there is no particular reason that maths teachers should be experts in the teaching of moral judgement or sexual ethics. There are good reasons these questions were mainly left to parents for a long time.

Sadly, on this one parental choice of schools isn’t much of an answer to this divergence of viewpoints: insofar as parents are able to exercise choice about which school their child goes to, the content of the RHSE curriculum is unlikely to be a big factor for most (if they can even find out what is being taught).

While we can never get to a 100% consensus, I think we need to get to something that a greater proportion of parents can be happy with - but that will mean reining in the wild west of activist sex education providers who are pushing inappropriate content to suit their own interests.