Illegal immigration: how we got here

Why it's become harder to control illegal migration and deport people - and what the Rwanda deal aimed to fix

Following the Supreme Court’s verdict on the Rwanda case there has been lots of discussion: both about the specifics of the policy, and also about illegal immigration, asylum and deportation more widely.

The post is in two parts:

Part A) The context of the small boats; the rising proportion of people able to claim asylum, and the increasing difficulty of deporting people

Part B) Why it has become difficult to control illegal immigration or deport people; and why various European governments, including the UK, are looking at new ways of doing things.

Part A)

The small boats context

Since the early 2000s France and Britain have been working together to stop illegal migration across the Channel, which used to take the form of people jumping into lorries to stow away.

After camps like the famous “jungle” grew up around French ports, measures were put in place to stop this. Juxtaposed controls were put in place so that those caught stowing away could be handed straight back to the French authorities. After migrants overran fences during the 2015/16 migration crisis, stronger fences and perimeter controls were put in place. This worked, and things calmed down for a couple of years, but from 2018 on, significant numbers of people started people crossing in small boats. Despite a UK-France agreement in spring 2019, numbers quickly grew.

Since the start of 2018, over 110,000 people have arrived illegally in the UK via the small boats. Small boats account for just under two thirds of all detected illegal immigration.

Most are young men: nine out of ten are men, and 76% are aged 18-391.

Few people coming via the small boats have any documentation. Only about 2% have passports, making it very difficult to prove who they are, or where they are from.

In theory it is illegal to come to the UK in this way - and has been for a long time. But most coming on the small boats claim asylum.

As the government notes:

The majority of small boat arrivals claim asylum. In the year ending June 2023, 90% (36,169 of 40,386 arrivals) had an asylum claim recorded either as a main applicant or dependant, at the time of data extraction. Small boat arrivals accounted for over one-third (37%) of the total number of people claiming asylum in the UK in the year ending June 2023. Seventy four per cent of all small boat asylum applications since 2018 were still awaiting a decision as of June 2023.

We won’t know for some years how many of the people coming on small boats will be successful in claiming asylum. We do know that since January 2021 their cases should have been inadmissible, but that so far only 23 people have been deported (to other European countries).

But we can be confident that almost all of them will stay in the UK anyway, unless something massive changes. The overwhelming majority will either be given asylum or be refused, but not removed.

If you can make it to the UK, you can stay

Success rates for asylum claims have been climbing over time, and the proportion of those who are refused asylum who actually end up leaving has collapsed since the middle of the last decade, as legal obstacles to deporting people have mounted.

Source: Home Office, Immigration System Statistics Data Tables, Asy_04

Because of the long lags in the system - to try and get documents from countries where this is near-impossible, and because people can make multiple appeals - there is greater uncertainty about how many recent claimants will end up staying.

But if we look back a few years, fewer than 5% of those who claimed in 2017 are still awaiting a decision, so we can be highly confident that only about one in ten of those who claimed asylum in that year actually left the country.

The proportion of those turned down for asylum who are actually made to leave is now very low. The Oxford Migration Observatory estimated that nine in every ten people who were refused asylum by the Home Office in 2020 were free to remain in the country.

In November 2023 the Home Office admitted it does not know the whereabouts of more than 17,000 asylum seekers whose claims have been discontinued.

The bottom line is: if you can get to the UK, you can stay, either by getting asylum, or be remaining anyway.

The growing asylum challenge

This matters, because the number of people seeking asylum has gone up dramatically, driven by the large number of small boat arrivals.

The graph above underplays the significance of what’s happening.

Unlike in the noughties, the large number of asylum claims in recent years is happening despite the fact that we have opened large non-asylum safe and legal humanitarian routes for the most significant source countries: Ukraine, Hong Kong, Syria and Afghanistan.

Asylum only accounts for about half (269,000) of the 529,000 people who came to the UK in the last five years via these humanitarian routes combined. That is a significant number of destitute people to provide housing, public services and welfare for.

To put it in context, substantially more people have come via the humanitarian routes than have come for work.

Of net non-EU migration of 2,008,000 over the last five years, 309,000 people came for work compared to 529,000 on the humanitarian routes2. Asylum claims alone at 269,000 contributed nearly as much to net migration as those coming for work.

Of course, many refugees do work and also contribute in other ways. My childhood Christmases (and many other weekends) were brightened by sharing empanadas with a Chilean refugee who had fled from Pinochet, who made a huge contribution to our local community.

But refugees are often destitute people with a lot of problems and may not speak English. Refugees in the UK are four times more likely to be unemployed than people born here, and on average earn about half the amount per week that UK nationals do.

This means that while it is right to shelter desperate people, there is obviously a net cost to the taxpayer from doing so. The government states that the asylum system “currently costs the UK some £3 billion a year and rising, including nearly £6 million a day on hotel accommodation.”

The pressure on our asylum system is only likely to grow in the coming years. If we look at the top ten countries from which we have accepted the most asylum seekers since 20083, the UN forecasts that their population will increase by 50% over the next 25 years - more than twice as fast as the world average.

This is likely to mean many more claims, even before we add in any other considerations like the increasing ease of travel, or youthful populations.

The increasing difficulty of removing people

People can only be put into immigration detention if there is a prospect of their imminent removal: that is, that their case is over and everything else is ready for their removal (which I will come back to).

However, even for those who are detained under these stringent tests, a falling proportion leave detention because they are actually removed from the country.

Instead, a growing proportion are bailed, including those who find a new ground for appeal. They may suddenly remember or discover some new reason they cannot be removed and start a new appeal. Only about 30% of those leaving detention are now being removed.

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics, Det_03

Difficulties deporting foreign national offenders

Compared to failed asylum claimants, one category of people who might be thought easier to deport are foreign offenders. But the growth of human rights case law and various other legal obstacles (explored below) have also made this difficult.

For example, in December 2020, 23 criminals were removed from a flight to Jamaica after lawyers lodged last-minute appeals mere hours before the flights were due to take off. The prison sentences of the 23 who escaped deportation totalled 156 years and one life term, for crimes including murder, rape, child grooming, dealing Class A drugs and possession of firearms.

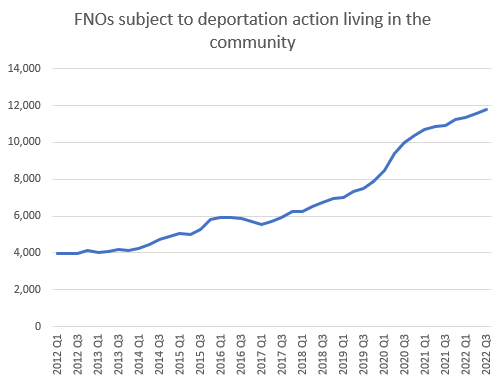

As a recent CPS report pointed out, there are now almost 12,000 FNOs subject to deportation action living in the community having finished their custodial sentences, nearly triple the number of 2012. Between 2012 and 2022 numbers grew just over 750 a year. Robert Jenrick has had some success in improving things recently, but this is a large number.

Government data suggests that between 2012 and 2019 there were a bit over 1,700 appeals against deportation lodged each year and a bit over 500 were successful. People can have more than one appeal throughout the deportation process.

Source: Home Office, Immigration Enforcement Transparency Data, Q3 2023, FNO_08

Part B)

Why did it get so hard to stop illegal immigration or deport people?

There have always been rules on who can and can’t come to the country. Since 1793 the UK has had legislation on the issue, spurred by concerns that some of the people arriving as refugees from the French revolution were in fact agents of the French (the sort of dilemma we still face). Since the same date there has been a part of the Home Office dedicated to enforcing the rules. The first person put in charge of this unit, William Huskisson, was, coincidentally, the first person ever run over by a train4.

The chain of things that needs to happen to deport someone is formidable, and if anything breaks at any point it doesn’t work:

Home Office have to find and serve papers telling the person they have no right to remain (people are not detained so this is hard and many disappear).

The country they are to be sent to have to have accepted the return and issued travel docs to they won’t be refused entry (many countries don’t cooperate).

All legal cases must be over (administrative review, asylum, human rights, modern slavery).

No new cases have been launched (actually many remember some new fact about their situation that allows a new case, or their situation changes because they find a partner or have a child or their health changes or the situation in the third country changes).

All the logistics have to work (detention, escort, flight or accommodation sometimes fall through).

Growing numbers of people making successful claims for refugee status

In 1951 the UK agreed the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. This built on a previous convention from 1933, including the principle of non-refoulment which is so central to the Rwanda case. It defined a refugee as someone who:

a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country;

Compared to contemporary immigration law it was limited in the following ways:

It only applied to European refugees.

It only applied to people who were refugees as “a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951.

There was no mechanism for enforcement.

The UK took steps to ensure it would not create a statutory right to appeal against decisions, so the government could keep its then wide powers of discretion.

The geographical and time limits were only removed later with a 1967 protocol.

The convention was agreed in a different world in which mass air travel did not exist, and travel was unaffordable for many in poor countries.

The 1951 system sets up particular incentives for governments. On the one hand, there are no quotas or caps, and strong limits on failed asylum seekers being sent back. So there are strong incentives for those who want to move to get into developed countries any way they can.

On the other there are is no quota or requirement on governments to take people who can’t make it to your country. So there are strong incentives for governments to make it difficult or unattractive to come in the first place.

A number of people argue we should turn this around: instead of first-come-first-served, we would decide how many refugees to take in, and then resettle people who have already been processed as refugees by the UN and the like, meaning they could go straight to being integrated rather than spending years arguing over whether they should be in the country. This would only work if it was an alternative to the current system, not on top: we already have safe and legal routes.

The other key way in which the 1951 text has grown over time is the interpretation by officials and courts of what it means to have:

a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,

This is of course subjective, and difficult to work out.

Many countries oppress different groups: homosexuals, people of minority religions like Christianity; members of political parties.

Officers read reports on the situation in different countries. There are endless questions of fact or degree. Are you really a member of this political party or this religion? Do you practice your lifestyle / faith / political persuasion quietly or are you a prominent target? Often there is variation between different parts of the same country and different time periods.

Immigration officers and courts face almost impossible questions of judgement. Absurd-sounding tests (can you name the mother of Jesus?) can weed out those who are obviously bogus, but given the high stakes, most people learn to play the game.

To get a sense of what officials and courts have to grapple with, one case in October 2023 involved the courts trying to decide whether a gentleman who had not gained asylum in two other European countries should get asylum here. Having used various agents to help him get around, he travelled from Iraq to Turkey, Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Holland.

He arrived clandestinely in the UK in 2017. He said he had applied for asylum in other safe countries “by mistake’’. He says he is at risk if returned because his girlfriend’s family are in a different political party. His appeal against early judgements against him has been allowed.

Case law has gradually broadened the definition of groups and also increasingly come to offer refugee status to people at risk of persecution from non state actors. Both would have surprised the signatories of the 1951 text. Lots of these can be questioned.

Eritrea has had a final grant rate of over 90% in recent years. An Eritrean man who leaves without an exit visa may be punished on return and made to do military service. But should that mean we cannot turn down applications from that country?

In Iran (from which around 80% of claims are granted protection) Christians and homosexuals face discrimination. Should anyone from that country who says they are one of these two be allowed to stay?

Should an Albanian who says they are at risk from a blood feud back home be automatically allowed to stay?

Inexorably the number of people who can claim asylum in the UK has grown.

One recent study added up statistics from various sources on persecuted racial, religious, national, social (including LGBT) and political minorities on a country by country basis; as well as populations in areas of ongoing conflicts including civil wars, insurgencies and invasions; and UN estimates of international refugees and people in modern slavery. It concluded that:

“The 1951 Refugee Convention now confers the notional right to move to another country to another country upon 780 million people, at a conservative estimate – something that was unthinkable when it was originally drafted.”

Even if people cannot claim asylum on this basis, there are numerous other legal avenues for them to avoid being deported.

Why is it so hard to deport people now?

As noted above, as well as a rising proportion being granted asylum in the UK, it has been becoming more difficult to remove people who have no right to be here.

The Modern Slavery Act 2015, via its National Referral Mechanism (NRM), has increasingly become the first line of defence for illegal entrants in Britain, not least those arriving via small boats. People claim to have been victims of modern slavery.

But far and away the most important legal change has been the growth of case law associated with the European Convention on Human Rights, signed in 1950. While the 1951 Refugee Convention had no court or enforcement mechanism at the start, the Convention has its own court in Strasbourg.

Unlike Germany the UK has a dualist legal system, meaning treaties don’t directly apply, so the UK was historically able to ignore rulings of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. But in 1998 the Blair government incorporated the convention into domestic law, meaning people could use their ECHR rights directly in domestic courts.

The Blair government may have rued this move quite quickly. In 2006 the courts ruled on the case of nine Afghans who hijacked an airliner in Afghanistan and held its occupants at gunpoint for four days at Stansted Airport in 2000. The court granted them leave to remain on a claim heavily based on ECHR rights.

Case law has shifted the meaning of some of the rights in the Convention in a way that would have stunned signatories. Numerous articles are used to appeal.

As an example, a government consultation listed some cases which show how the balance has shifted on Article 8 of ECHR:

Case X

Case X was a foreign national who had leave to remain in the UK, and who committed a series of crimes including common assault, battery, destruction of property and grievous bodily harm.

Whilst Case X was serving a custodial sentence for possession of cocaine with intent to supply, the Home Secretary made a deportation order against Case X. Case X appealed, claiming it would violate their Article 8 right to a private and family life. The Asylum and Immigration Tribunal found that it would be a disproportionate interference with the appellant’s rights to deport them, given their relationship with their child.

Case AD (Turkey)

In 2018, a Turkish national was convicted of an offence of grievous bodily harm and sentenced to 54 months’ imprisonment. In September 2019, the First Tier Tribunal allowed his appeal against deportation, on human rights grounds. After protracted litigation, relying on his period of lawful residence and marriage to a UK national, the Upper Tribunal allowed the appeal on Article 8 Convention grounds.

Case OO (Nigeria)

In 2016, a Nigerian national was convicted at trial of two counts of the possession of Class A drugs, namely crack cocaine and heroin, with the intention to supply, and the concealment or conversion of criminal property. He was sentenced to a total term of imprisonment of four years. In 2017, he pleaded guilty to two offences of violence; assault occasioning actual bodily harm and battery. He was sentenced to a total of eight months’ imprisonment, to run concurrently with the four-year sentence he was already serving for his earlier convictions.

In 2020, the First Tier Tribunal allowed his appeal against deportation on Article 8 grounds. Before the Upper Tribunal, the Home Secretary argued that insufficient weight had been given to the public interest in deportation and that the findings that very significant obstacles would be encountered in integrating in Nigeria were not made out. The Upper Tribunal upheld the findings relying on OO’s ‘very significant obstacles’ to integrating back in Nigeria.

I don’t think this is what Winston Churchill intended when he set up the Council of Europe.

On top of the growing tendency of the courts to not allow people to be deported to countries that will take their citizens back, there are a number of countries that simply do not want to cooperate with the UK, and do not want a normal diplomatic relationship with the UK or our European allies. While we can press normal countries to take their citizens back by threatening to limit visa issuance, there are a number of countries which simply don’t care about such pressures.

What are people worried about?

Does any of the above matter? You might think that it is a bit unfair that more come illegally and cannot be removed, but still not think this is a big problem. You might think the £3 billion price tag is larger than you’d like, but not the end of the world.

I think the fairness point is important. People naturally worry about whether the system is being abused. A couple of months ago a rash of videos made by asylum seekers in the UK showing off their hotel accommodation made headlines, and contributed to concerns this would create a pull factor for more to come illegally.

But the most important point is that being unable to control illegal migration means losing control over who is coming to the country, risking importing dangerous people.

One of the primary reasons we have immigration control is to filter arrivals and prevent dangerous people from coming here. But if people can simply arrive illegally with no checks and then stay, this is undermined.

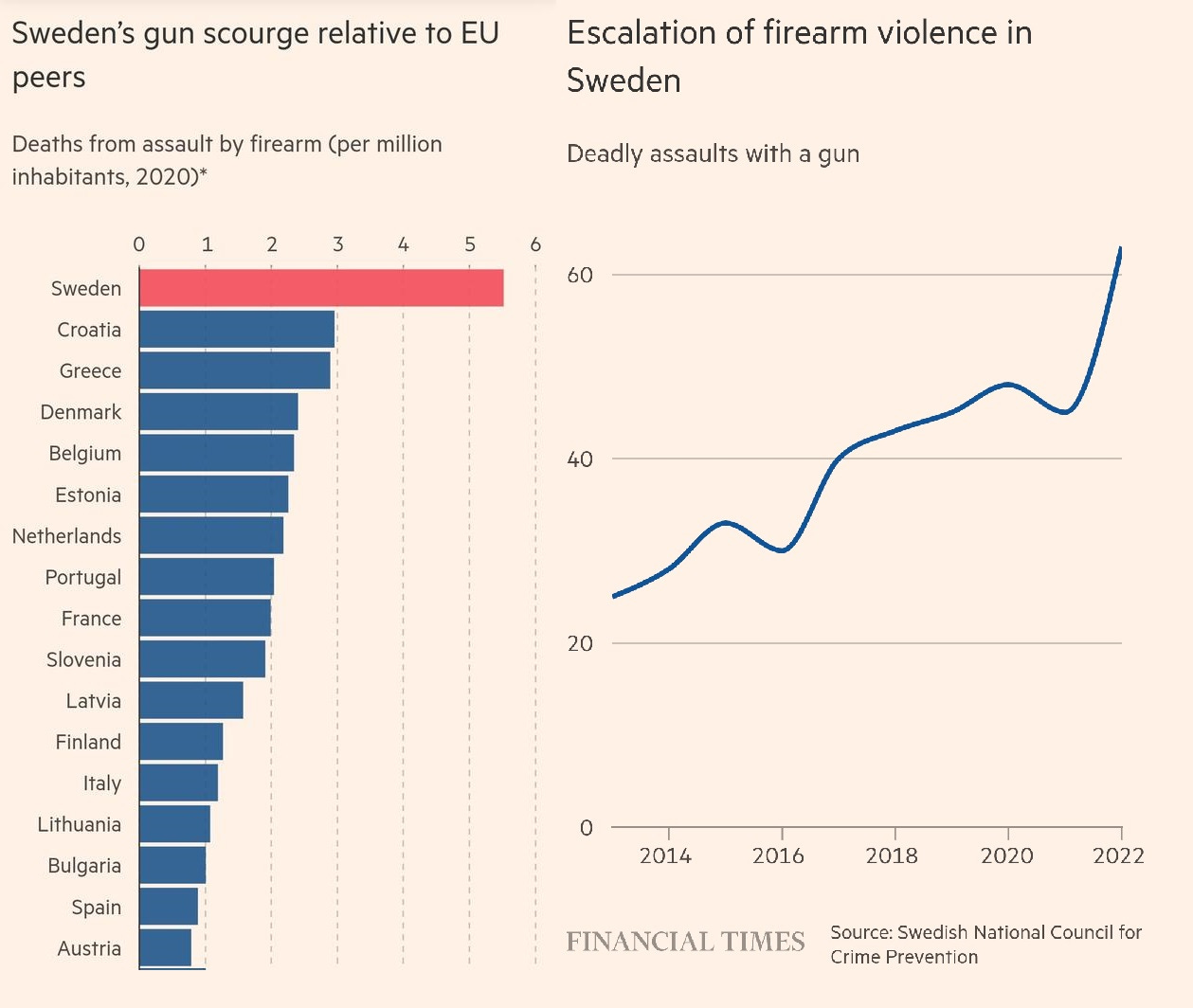

Sweden certainly offers a cautionary example of how not to do things.

In a previous post I argued that we should have lower and more selective immigration policy, to make the UK the “grammar school of the western world”.

In contrast to the selective approach, tolerating illegal and therefore unfiltered migration brings a much worse ratio of risk to benefit, as well as undermining the rule of law.

The Swedes have taken a very liberal approach to asylum and aimed to be a ‘humanitarian superpower’. Over the period 2008 - 2022 they accepted more claims that the UK. Per head this was the second highest rate of any EU member state after Cyprus, about four times the rate per head in Western Europe5. Syria has overtaken Finland as the most common country of origin for Swedes of foreign origin.

The results have been disastrous, with an epidemic of gang violence. A recent Financial Times report noted that, “The Nordic country has gone from having one of the lowest levels of fatal shootings in Europe to one of the highest in just a decade.” In 2022 more than 60 people were killed in gun violence, and there were 88 bombings.

After widespread riots left 100 police officers injured the former centre left Swedish PM said that immigration had fuelled crime, saying that “Integration has been too poor at the same time as we have had a large immigration,” warning that it had created “parallel societies”. Under a new PM, the Swedish government has tacked in a more restrictionist direction and the new PM directly blames “irresponsible immigration policy” for the crime wave, with a mountain of evidence now showing that migrants to Sweden are hugely more likely to commit crimes.

Sadly, the UK has also seen numerous cases of serious crimes committed by people who should not have been in the UK. The list of cases makes for heartbreaking reading. Having a large and growing number of Foreign National Offenders in the country and not removed is a danger to the public.

A report by the Henry Jackson Society lists a large number of terror offences committed by people who should not have been in the UK.

Where European countries are going

There has been a dramatic decrease in our ability to deter illegal immigration. Growing numbers are either granted asylum/protected or prevent themselves being removed anyway.

This has not come about through conscious political choice or democratic means, but instead by the growth of contentious case law, transforming the meaning of texts like the ECHR and 1951 convention in ways that would have stunned their original signatories.

The result is unfair to those who have played by the rules, undermines the rule of law, poses risks to our security and comes at a significant cost.

It is for this reason that politicians have long sought safe third countries to either:

send failed asylum seekers from the UK to;

process asylum claims offshore before coming to the UK; or

process asylum claims on our behalf, and accept those who succeed

The deal with Rwanda is under the third heading, one reason the Supreme Court struck it down. Tony Blair’s government worked to get a deal with Tanzania (type 1 above) to send failed asylum claims there.

The Blair government also worked to agree a deal with other EU member states that would have seen asylum processing in third countries (type 2 above).

This discussion has never really gone away and a number of EU member states are working on offshore processing.

Two camps are to be built in Albania to house migrants rescued at sea by Italian boats while Italy processes their asylum claims. The EU has so far ruled this is not illegal under European law.

Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria are looking at similar schemes. The UK and other European countries are talking not just to the Rwandans but safe other countries who are all watching to see what happens with Rwanda.

Safe and legal routes - a fake solution

During a recent phone in show on the radio I was trying to explain why Rwanda is a safe third country. The Rwandan government is definitely not perfect: it came to power not via election, but by successfully ending a genocide which had claimed the lives of between 7 - 11% of the population.

The country is extremely safe, and whether in a village or the capital I felt safe walking around at night when I visited. The economy is booming and the government seems to be working hard to erase the ethnic tensions that fuelled the genocide. Corruption levels are very low compared to countries in the region.

It is breathtakingly beautiful: a country of red earth, green hills, incredibly tragedy, but also new hope. Multiple EU member states want to work with the Rwandans.

They care about their international reputation and with the whole world watching and a high level of supervision from the UK and potentially other international partners I think they would err on the side of caution and strain every sinew not to put a foot wrong.

That the scheme was legal and reasonable was the view of the High Court and most senior judge on the Court of Appeal. So opinions on this question can and do vary, but Parliament would be well within its rights as the highest court in the land to judge it safe.

After the phone in I mentioned, Sunder Katwala, a pro immigration lobbyist, has complained that I made the UK type 3 proposal above sound like type 2 - and indeed I should have been clearer.

But Sunder’s counter proposal is absurd. His view is that if we and other European countries simply make it easier to get refuge legally then illegal migration will cease.

This won’t work: demand to move to developed countries like the UK is near unlimited compared to our capacity to absorb it. Billions of people would be radically better off if they moved to the UK or elsewhere in Europe.

Example: in the last 18 months over 1,600 people from India have crossed illegally to the UK via the small boats.

This is despite the fact that in the year ending June 2023 India was the number one nationality for legal migration into the UK, with 253,000 coming. India is the world’s largest democracy and a booming, emerging superpower with a successful space programme.

Unless you are prepared to have totally open borders (which few advocates admit openly to supporting), then any “safe and legal” routes will have either a limit, or there will be countries to which they do not apply, at which point people not included will seek to come illegally.

Sunder suggested that offering just 40,000 safe and legal places would solve the problem and soak up the demand to enter illegally. But over the last five years we have taken more than that on average each year via safe and legal routes, and despite this still had 110,000 people coming via small boats, and a total of 269,000 people via asylum.

We have taken half a million people via humanitarian routes. But sadly we cannot have an unlimited scheme for every country in the world that is poorer or more oppressive than the UK.

Legally it couldn’t be clearer: the refugee convention doesn’t give refugees the right to pick which safe country they go to, just a right not to be sent somewhere they will be in serious danger. So if other safe countries will take them, that’s legal.

Conclusion

A serious problem has been created by courts interpreting texts in ways their signatories would not have agreed to, plus mass travel, plus criminal networks, plus uncooperative governments in third countries. The small boats trade is criminal, dangerous, and undermines faith in the rule of law.

The various schemes that European governments and the UK government are looking at are a reasonable and proportionate response to the problem.

I look around Europe and see Dublin on fire and the sensible centrist voters of the Netherlands now electing a far right party. I see what has happened in Sweden, but also in the UK on a smaller scale.

The challenges of illegal migration and our inability to deport those who should not be here are real and growing, and have to be dealt with in a sensible and proportionate way. The alternative is a mess.

Home Office: Irregular Migration Statistics, year ending June 2023, Irr_02c

EU net migration was basically flat over the same period: net migration of 45,000 compared to 2,008,000 for non EU.

Including asylum claims, grants of humanitarian protection and discretionary leave, the top ten were: Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria and Zimbabwe.

Ironic, given that most people put in charge of this policy area feel that they have been thrown under a bus, not a train.

Eurostat, Final asylum decisions, [migr_asydcfina] / population [demo_pjan]

Hello - if people can be actually got to Rwanda the total number can be scaled - I have heard more than hundreds suggested. There's uncertainty about how many people would have to go for it to work as a deterrent. I do think we should also do other things, not just have Rwanda as the only option. While the Albania deal is good, I don't see other similar deals out there adding up to "stopping the boats" without a Rwanda like deterrent

I agree with some of what you say but the elephant you haven't dealt with here is that the Rwanda scheme is fundmanetally impractical - even if you disagree with the Supreme Court judgment that it is unsafe ("the Rwandan government definitely isn't perfect" might be the understatement of the year...)

There is only enough capacity in the Rwandan system to take more than a few hundred UK asylum seekers. Your ally in this cause, Nick Timothy, acknowledged in his CPS paper that would not be enough to act as an effective deterrent, especially given how desperate people coming to the UK are.

So putting aside all political, legal, and ethical issues, it still wouldn't resolve the problem, and it would fail to do so at enormous cost (the conservative Home Office estimate being £170k per asylum seeker).

What has worked in the last year is the Albania deal, which has reduced small boat numbers from 2023 by around a third. These kinds of agreements are slow and laborious but they actually have an impact, and that route could be pursued with other countries to which return is at the moment, very difficult.