Honey, we didn't shrink the kids

A bogus argument about children's height and austerity

Last year there was a huge amount of coverage of a story which suggested that British children were both shrinking, and being overtaken in terms of their height by children in other countries. The message was clear: austerity was to blame for shrinking our children!

This report was then rehashed in a Labour press release this month.

There’s just one problem.

The “data” it is based on is wrong, and our children are not shrinking.

Let’s revisit the argument first. According to Labour List:

“The height of the average British five-year old girl has fallen by 27 places in international rankings over the last three decades, Labour said, with the average five-year-old boy falling by 33 places.

Of course, there could be no doubt who and what was to blame.

The Guardian headline told us: “Britain’s shorter children reveal a grim story about austerity”.

The Guardian quoted Professor Tim Cole from Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, saying that:

“austerity has clobbered the height of children in the UK”.

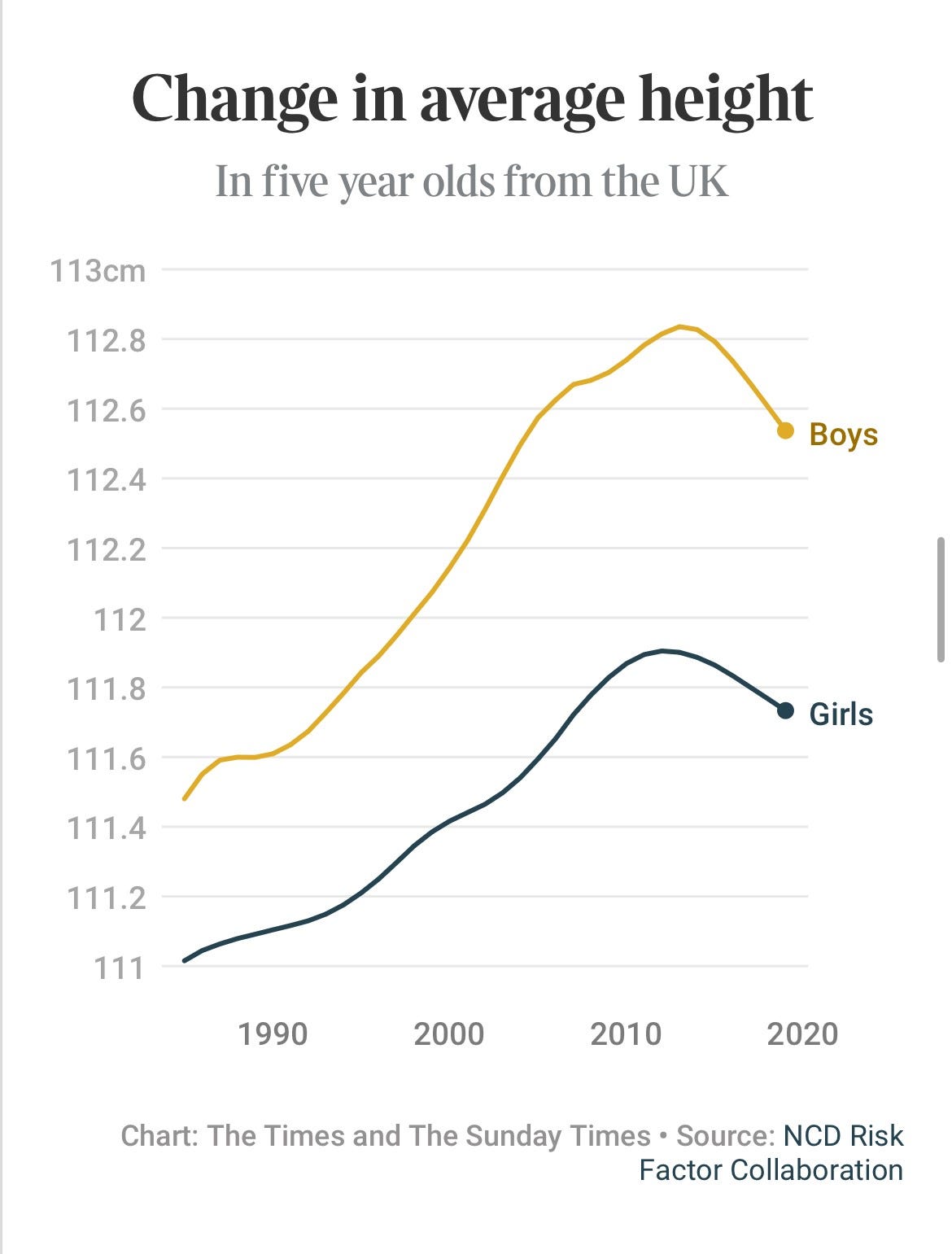

Graphs circulated in the media - and on social media - showing how our children were shrinking in front of our very eyes. Here’s one that appeared in the Times:

Hang on a minute

The data above which purports to show that our five year olds are shrinking (and that the UK is falling behind other countries) is sourced in the graph above to the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration.

If we head over to their website, we see that their data is in turn based on this 2020 paper from the Lancet.

But where it that data from?

Answer: It’s not actually data - these are model-based estimates based on blending together loads of previous studies and data sources. Estimates for a given country were based not just on data from that country, but also informed by data from other countries, via a complex algorithm. The authors explain:

“We used a database of cardiometabolic risk factors collated by the Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factor Collaboration. We applied a Bayesian hierarchical model to estimate trends from 1985 to 2019 in mean height…

estimates for each country and year were informed by its own data, if available, and by data from other years in the same country and from other countries, especially those in the same region and super-region, with data for similar time periods. The extent to which estimates for each country-year were influenced by data from other years and other countries depended on whether the country had data, the sample size of the data, whether they were national, and the within-country and within-region variability of the available data.

We pooled data from 2181 population-based studies… We searched MEDLINE (through PubMed) for articles published from inception up to Aug 2, 2020… The database and its criteria for data inclusion and exclusion are described in the appendix.”

What the authors of the study are trying to do is make rough estimates for countries across the world, including for developing countries and periods where data is very scarce and/or low quality. That is a reasonable thing to do: many countries won’t have much in the way of data.

But such model-based estimates (and that’s how the authors describe them) produce odd and wrong results for the UK, compared to the direct, gold-standard data on children’s height that we have here. Let’s compare the model output to the data.

The National Child Measurement Programme

In England we measure the height and weight of all primary school children twice: once in reception, and once in the last year of primary school. This is not an estimate or a survey. We are literally measuring each child, like a census. You could not have higher quality data. Even so, the DHSC present it with two warnings about the data.

1. Analysis of the NCMP data in the first three years show lower participation rates in the programme and suggested selective optout of children with a higher body mass index for age. It is possible that average height figures for year six for 2006/07 to 2008/09 could have been affected by this lower participation in the measurement programme.

2. Some of the variation in height across all NCMP years may be due to variation over time in average age of children when measured. In 2019/20, children were only measured up to March 2020 so the average age of children and therefore mean height was lower than other collection years. In 2020/21 the NCMP data collection did not start until April 2021 so the average age and therefore average height was higher than other collection years.

Accordingly, in the chart below I have taken out the years they flagged as problematic: both the early years, and the two pandemic years which caused the average height to first fall, then seemingly spike up.

Children are aged between four and five years old in reception and between 10 and 11 years old in year six.

The model-based estimates from the Lancet paper that caused all the coverage are for children aged 5. Here is how they compare:

I don’t know whether the bump up following the pandemic will be sustained. But there was essentially no change over the years before it, in those years where austerity was supposedly “clobbering” children’s height.

The NCD appendix lists the sources for the UK. Clearly, not all these sources are created equal. Here is the list of data sources that are being fed into the algorithm for the UK in 2016/17, and the sample size for each. One of these is not like the others:

Swan Linx project = 606

Health Survey for England = 927

National Child Measurement Programme 430,101

National Diet and Nutrition Survey = 255

Health Survey for Scotland = 672

The algorithm that is blending all these together is complex, and I am not totally sure why it is giving such a different (downward) trend to the gold-standard, massive-sample-size data we have from the NCMP. I don’t think it can plausibly be about England vs the UK - 85% of 5-year-olds in the UK are in England, so children in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland would have to be shrinking to Smurf-size for that to explain it away.

What about other countries?

OK, so we aren’t actually shrinking the kids in the UK. But we are being overtaken, right? And surely that’s all the fault of George Osborne’s Austerity (TM)?

Hmmm. If we look at countries around the world over the period during which British 5 year olds supposedly shrank, a surprising number of other developed coutries are supposedly seeing shrinking children.

In Europe there are big drops in Switzerland, Denmark, Germany and Belgium. Elsewhere we see big drops in New Zealand, Japan and Canada. That means they too will be losing ground in the rankings in the same way that the UK supposedly is.

While the average five-year-old boy in the UK may have dropped 33 places in the ranking of the NCD estimates between 1985 and 2019, plenty of other developed countries have too, like New Zealand (also down 33 places) Austria (down 35), Japan (down 37), Switzerland (down 49) and Belgium (down 61) places.

It seems a bit surprising that George Osborne’s Austerity (TM) has had such a big impact on children in Switzerland and Japan.

Don’t get me wrong. The UK and other developed countries will lose ground in relative terms as developing countries develop - and particularly where countries emerge from conflict. I can well believe that children in China, Vietnam and India really have been catching up on their developed country peers in recent decades.

What I am really objecting to is:

the uncritical acceptance of some of this data,

the uncritical attempt to read across from it to living standards for children;

and the attempt to read across from that to a critique of policy.

For example: among the countries that supposedly overtook the UK in this period are countries like Haiti, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, and North Korea. These are not all social democratic paradises where small people are being nurtured by Enlighted Early Years Programmes.

Given that I can see the NCD estimates look wrong for this country, I do wonder about the data for some of these other countries: it must inevitably be pretty limited.

For example, North Korea is a country characterised by frequent food shortages and the regime burning tyres for fuel. But the NCD estimates suggest that not only have the heroic five-year-old worker-comrades of North Korea overtaken the UK, but that they are also now bigger than their peers in countries like Canada, the USA, South Korea, and Switzerland. While numerous sources of data are listed as flowing into the model results for South Korea, no data sources at all are listed as contributing to the North Korea result. So I don’t know where the number comes from, and I certainly don’t read it and jump to the conclusion that North Korea would be a better place to bring up my kids than Canada.

And there is then a further logical leap: from the conditions children are experiencing in different countries to the policies pursued by particular governments.

In the UK the proportion of children in who are in relative low income after housing costs has changed very little over the last 20 years, and the proportion in absolute terms is down. The whole narrative from “exploding” poverty to “shrinking” children is flawed from start to finish.

Conclusion

It’s perfectly reasonable to have a discussion about public spending; and good to debate child health. But what has happened here is that people have grabbed at and exploited some new numbers, to try and make a political argument. And it just doesn’t stand up.

The numbers are wrong for the UK. They look kooky for other countries, and I certainly wouldn’t use them as an indicator of child welfare around the world. And the supposed logic which flows from austerity to “shrinking kids” is wrong.

Given the unprecedented crisis in the public finances at the end of the noughties, the late Alastair Darling, a serious person, had pencilled in spending controls in his final budget which were similar to those actually delivered by the subsequent coalition government. Maybe they would have been distributed differently. Who knows. We can have a debate about the choices the coalition had to make, but we should have a debate that isn’t based on junk.

I cannot find any data in the Lancet paper that shows the trend shown in the Times article. The article says "[o]ur primary outcomes were population mean height and mean BMI from ages 5 to 19 years."