Free the trees!

New data on woodland shows how may trees there are in your neighbourhood - and I have a modest proposal to make life massively better for everyone

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

- Philip Larkin, The Trees

This post is unapologetically pro-tree. Woodlands are lovely places to be, forests are crucial for nature, and trees massively improve streets in our towns and cities.

The UK is a bit short of trees compared to most of Europe. Most of our land is farm or moor if it isn’t urban. Just 13% of the UK is forest or woodland, compared to 43% of the EU. Countries like Sweden and Finland are about two-thirds forest.

The government produces data on the amount of woodland in different local authorities. That’s useful, but there’s obviously massive variation within local authorities.

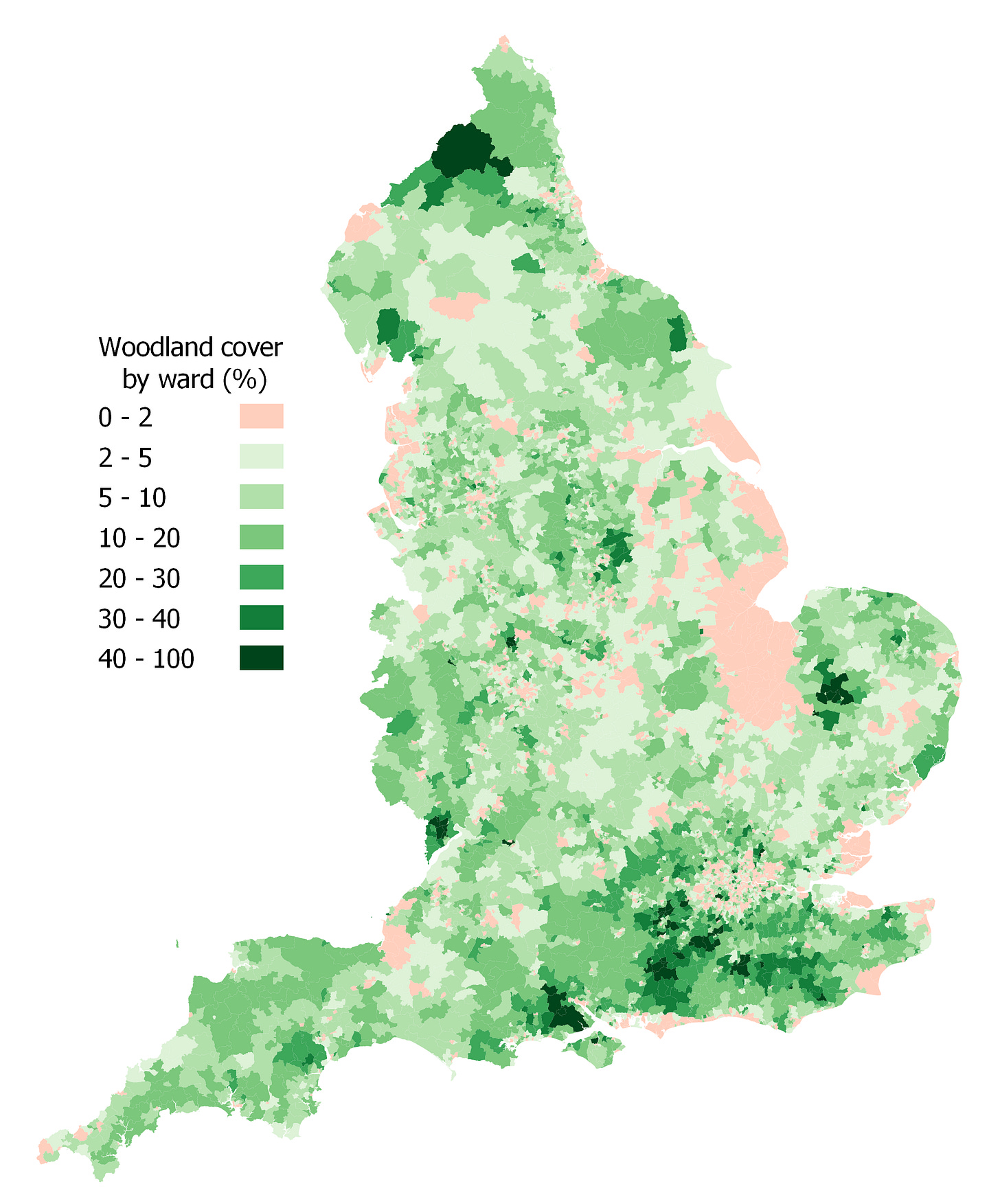

Through a recent Parliamentary Question I have managed to get DEFRA to release much more granular data for the first time, showing the proportion of each ward in England that is covered in woodland. The results are below. First, here’s England as a whole:

The obvious difference is between the urban and non-urban areas - which is the focus of this post. But there are other big differences too.

Places like Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire are intensively farmed, and have little woodland.

And you can really spot that big pink area around the Wash which used to be under water.

If you are looking at this online, you can zoom in within each of the regional maps below (it was too big to do in one go):

Create woodlands

The last Conservative manifesto said that:

“The new £640m Nature for Climate fund will increase tree planting in England… The government would work with the Devolved Administrations to triple UK tree-planting rates to 30,000 hectares every year – space for at least 30 million more trees […] equivalent to 46,000 football pitches.”

This was one of my favourite things in the manifesto. And an array of policies have been created to make it happen, including: the Woodland Creation Planning Grant; the Urban Tree Challenge Fund; the Woodland Carbon Guarantee; the Local Authority Treescapes Fund; Countryside Stewardship grants; three different Countryside Stewardship schemes; the Tree Health Pilot Scheme; the England Woodland Creation Offer and the Seed Sourcing Grant. Some of this reflects the shift away from the old EU agricultural production schemes towards funding farmers for environmental improvements.

At the local level councils have also got going. My county council in Leicestershire has a drive to plant a tree for every person in the county, and is already halfway there.

One of the challenges has been ramping up cultivation and nursery production; hence things like the Tree Production Capital Grant.

Another challenge has been finding the right places to plant without taking out the best and most productive agricultural land - to that end the Forestry Commission has undertaken a massive mapping exercise, to figure out which land can be used and has created a Land App.

These practical challenges have meant the tree planting programmes have taken a while to get going. But 3,128 hectares of trees were planted in England in 2022/23 – a 40 percent increase on the previous year.

There are some tricky things to get right: as farm subsidies are reformed government must avoid creating massive winners and losers. There are multiple competing uses of land which can potentially push up the cost of farmland for farmers - including forest planting, but also things like solar farms (which I am very sceptical about in a UK context - they produce almost no energy when we most need it in winter).

I’m not going to get into this here, except to say that now that momentum has built up it would be a shame for the next spending review not to maintain the pace on woodland planting. But we need to be very careful about stiffing farmers, or pushing up land prices. Which is a DJ style link into my main point…

Street trees

If I have a seed of doubt (haha) about current tree policy, it is that the big national targets that have been set tend to favour planting trees where it is cheapest, which is often furthest away from where people live, so reducing the benefit to people.

Trees on streets have maybe the biggest benefit of all. But they cost councils to maintain and are seen as a pain by bureaucrats. I’ve written before about how this led to street trees in my constituency being ripped out. Proper planting and looking after of street trees does cost councils.

In some local authorities like Sheffield and Plymouth the battle between tree-loving residents and tree-hating bureaucrats has convulsed local politics. In both cases the ruling local party found that felling trees took an axe to their majority.

The think tank Create Streets produced a magisterial report called Greening Up on the almost insane, magical benefits of greening our urban environments:

Urban trees can cool city surface temperatures by up to 12°C;

Trees mitigate flooding: tree canopies mitigate run off and woodlands act as ‘sponges’ to slow the flow of water;

Urban greenery reduces air pollution by absorbing particulates from the air. studies have found street trees near a pollutant source reduced particulate matter by up to 85%;

Trees make people feel better: hospital patients who look out at an attractive environment require less medication; people’s perceptions of shopping areas are way better where there are trees; property is worth more in leafy areas.

The Woodland Trust charity also has a big report and campaign pushing councils to do more to get more trees in urban areas.

Reading Kuan Yew’s fantastic book, “From Third World To First”, I was struck by how much emphasis he placed on greening Singapore as part of his drive to make it into a civilised and attractive place to live. Greening our cities should be a key part of a LKY-style drive to civilise our cities, which should also include things like a war on street scars; music being played out loud on public transport; graffiti; litter; vacant shops; spitting; anti-social behaviour and the like.

A modest proposal

So, here is my submission for the next manifesto.

We should start by tree-lining every high street (there are about 7,000 in Britain).

Then we should set a visionary goal: to get trees growing on every residential street in the country.

The main obstacle to making it work is not finding the trees. The big supporting things we would need to do are:

Reforming local government funding formulas to support urban tree planting, to take away the financial disincentives they currently face to allow trees.

Hacking back the thicket of bureaucracy which makes it hard to plant street trees. (Create Streets had a mass of detailed suggestions on this).

(Above all) creating a sense of mission, so that all councils know they is something they have to deliver, rather than an annoyance / cost they can avoid.

Further reading:

https://www.treesforstreets.org/

https://www.treesforcities.org/

Free Trees for Schools and Communities - Woodland Trust

Hi Neil! I actually wrote about a similar data set from the woodland trust on tree equity here: https://uncover.substack.com/p/the-root-of-happiness-how-does-tree . This data set uses satellite data on tree cover but the granular data looks v similar to the dataset you reference here.

It highlights the extent to which the tree distribution is so heavily aligned with economic factors. Agree that we should be planting a tonne more trees (esp in cities), but we should also think carefully about the distribution of those trees.

Urban tree planting is a good idea. The woodlands policy is unfortunately a case of perverse incentives in action. If you have a piece of land available for tree planting but you leave it bare, trees will appear and survive much more successfully than introduced trees (at no cost). Unfortunately the huge grants for tree planting mean doesn't happen. Frustratingly there are virtually no grants for maintaining existing woodland which is generally on farms and mostly described as failing as they are so neglected but which are soaking up vastly more carbon than a new wood would for probably the next fifty years - and would sequester even more if properly managed.

To see how the system is really working in practice, look at adding trees to hedgerows. Seems like a good idea and a farmer can get £19 a tree for doing that, but the rules specify that a hedgerow tree has to be two metres tall. The cost of a two meter sapling would be well over £100. An opportunity lost